The forgotten history of the Hia-Ced O’odham

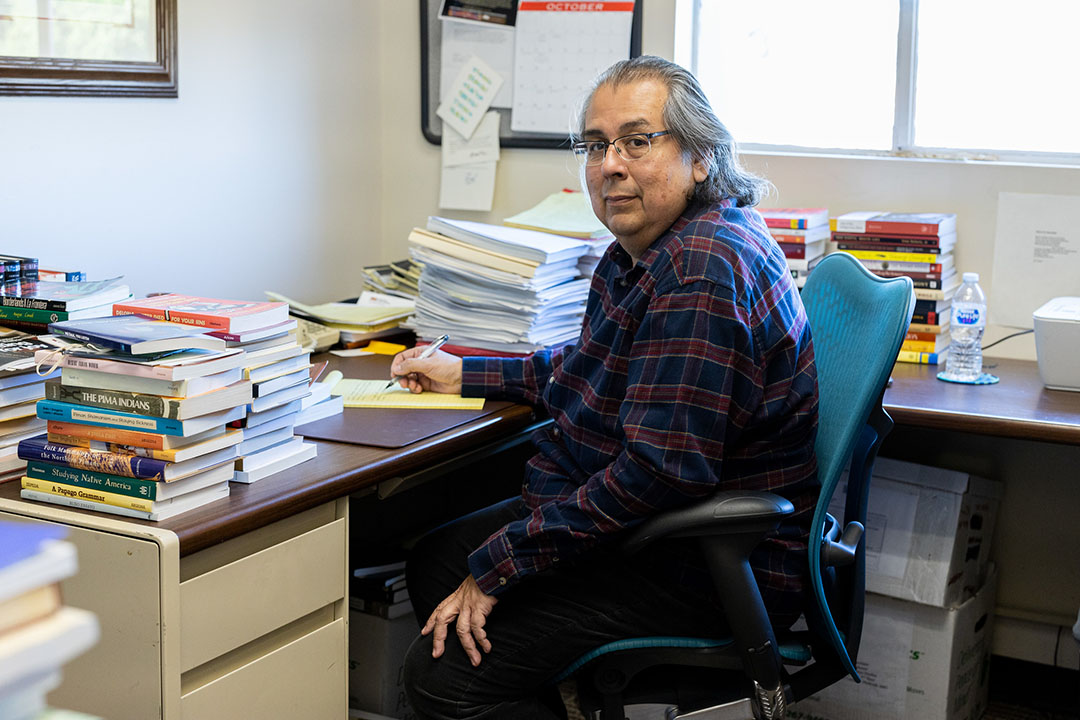

David Martinez, a professor with joint appointments at the American Indian Studies program and the School of Transborder Studies, and Lourdes Pereira, a student in the American Indian Studies program, are both supporting efforts to help their Indigenous tribe, the Hia-Ced O'odham, gain federal recognition. Photos by Meghan Finnerty/ASU

The Hia-Ced O’odham community, whose lands fall on both sides of the U.S.–Mexico border, is the only Indigenous tribe in Arizona that is not federally recognized. Two Sun Devils are working to change that.

David Martinez, American Indian Studies and School of Transborder Studies professor at The College of Liberal Arts and Sciences at Arizona State University, is related to the Hia-Ced O’odham through his maternal grandmother. He also serves on the board of the Hia-Ced Hemajkam LLC, the organization working to establish federal recognition for the Hia-Ced O’odham people and protect their lands and culture.

Martinez shared the story of how the Hia-Ced O’odham were once considered extinct, from the American perspective, and how this has impacted their ability to be federally recognized:

“In 1851, there was a yellow fever epidemic that swept through their ancestral land, between Yuma, Ajo and Sonoyta, in the southwestern part of Arizona,” said Martinez.

“As a consequence of that epidemic, as often happens in these situations, the Indigenous population migrated to other parts of their homeland to avoid the spread of disease.”

It was understood among the local O’odham communities that this migration to the eastern edge of their lands was temporary — a precaution in epidemic times. But because this happened at the start of the American occupation of the area, the Indigenous people were unable to return.

“As a consequence of the way that the Americans managed the land, in which they wanted to control every Indian population under its jurisdiction, the Hia-Ced O’odham stayed where they were.”

The Americans, in turn, assumed the Hia-Ced O’odham had abandoned their homeland and been wiped out by the yellow fever epidemic.

This was the beginning of over a century of struggles for a forgotten Indigenous transborder community.

Today, Martinez is documenting this history in his working manuscript “Elder Brother's Forgotten People: How the Hia Ced O'odham Survived an Epidemic to Claim a Place in Arizona's Transborder History,” which will become the foundation of the tribe’s petition for federal acknowledgment.

Preserving Indigenous heritage for generations

Lourdes Pereira, Martinez’s niece and a student in the American Indian Studies program, has been immersed in the Hia-Ced O’odham community, culture and language since she was young.

“My mom was incredible with making sure that we know where we come from and being involved in our community, and that’s where it really stems from for me, is my mom. And I know for her, our great grandmother, she did a fantastic job advocating for the Hia-Ced O’odham and creating a collection for us,” she said.

“There is just a lot of strong women in my family, and I'm very fortunate to have them.”

During her first year at ASU, Pereira became connected with the Labriola National American Indian Data Center, ASU’s Indigenous-led library, and became a student archivist. During one of the center’s workshops, she learned about community-driven archives. With that knowledge, she felt called to properly preserve her family’s collections and became an official archivist for the Hia-Ced Hemajkam LLC.

Her documentation will support the Hia-Ced O’odham in their petition for federal recognition, but this work is also significant to her on a personal level.

“For me, making my tribe become federally recognized is extremely important to me. But also with our community memory, our ancestral knowledge, I know how vital and crucial that is too, for it to be preserved for generations, for my children's children's children to be able to go back and to listen to these stories, to hear about our sacred sites, our oral histories,” said Pereira.

“That all to me is like breathing.”

The road to federal recognition

The process to become federally recognized is not easy.

There are two methods for a American Indian tribe to gain federal recognition: (1) submitting a petition or (2) congressional vote.

Petitions, submitted to the Office of Federal Acknowledgement, must include a historical narrative of the tribe from the 1900s, supporting evidence for the tribe’s historical existence, instances of previous government communications that mention the tribe, and a list of living members, to name a few.

“When you look at the guidelines for the petition, they want your historical narrative organized by decade, beginning in 1900,” said Martinez.

“It's not unusual to see a petition that's 400 pages long, so this isn't just filling out a five-page form and checking off the boxes.”

Professor David Martinez works in his office surrounded by books. Martinez is documenting the history of the Hia-Ced O'odham in his working manuscript “Elder Brother's Forgotten People: How the Hia Ced O'odham Survived an Epidemic to Claim a Place in Arizona's Transborder History.” Photo by Meghan Finnerty/ASU

For example, the Schaghticoke Indian Tribe, one of three current petitions in progress, submitted their 100-page petition in January of this year, and the review is not yet complete, according to the U.S. Department of the Interior Indian Affairs website.

The Pamunkey Indian Tribe, the last tribe to receive federal acknowledgment, submitted its petition in June 2009 and was officially acknowledged in January 2016. The Shinnecock Indian Nation, which originally submitted documents in 1998, was officially acknowledged in 2010.

Alternatively, tribes can gain federal acknowledgement through Congress.

“Congress can recognize anyone that it wants; it has that much power,” said Martinez.

“There have been tribes over the years that got federal acknowledgement status through the congressional process. So basically what that means is getting support from a congressman like (Raúl) Grijalva, who's willing to introduce a bill into Congress granting the federal acknowledgement status to the Hia-Ced O’odham.

“Of course, it would have to go through the normal legislative process, you know, including a positive vote in both houses. But that's another path that we're trying to pursue.”

Why it matters

Without federal recognition, Martinez says the Hia-Ced O’odham’s relationship with the federal government is like a stepchild.

“There are a lot of conversations that the Hia-Ced O’odham are not a part of, that maybe next door, the Tohono O’odham Nation, they're a part of, because they're a federally acknowledged tribe,” he said.

“And so it's not unusual for the Hia-Ced O’odham to have to depend on the Tohono O’odham to remind the federal government that they should talk to us.”

Recently, the development of the U.S.–Mexico border wall took place on Hia-Ced O’odham sacred lands.

An open letter dated Sept. 4, 2020, from the Hia-Ced Hemajkam LLC stated: “On March 20, 2020, Hia-Ced O’odham leaders traveled to the Organ Pipe National Monument to visit our sacred place, to see with our eyes and hear with our hearts the impact of the Border Wall on our aboriginal territory. Although the pond had noticeably decreased in water and the children’s shrine destroyed, the Quitobaquito Cemetery and reburial site were not disturbed.”

The border wall is one example of how federal acknowledgement and open conversations between the government and Indigenous communities could have helped preserve and protect their lands and resources.

Lourdes Pereira works as a student archivist at the Labriola National American Indian Data Center. Pereira's documentation as an official archivist will support her tribe in their petition for federal recognition. Photo by Meghan Finnerty/ASU

Just the beginning

The Hia-Ced O’odham have a long road ahead, but for Martinez and Pereira, federal recognition is just the beginning.

With support from Irasema Coronado, director and professor at the School of Transborder Studies, and Carlos Vélez-Ibáñez, founding director emeritus and Regents Professor at the School of Transborder Studies, Martinez is working to establish an Institute for Transborder Indigenous Nations at ASU that brings attention to the unique challenges that transborder Indigenous communities face.

“The center that I want to create will hopefully benefit not only the Hia-Ced O’odham, but all Indigenous people along the U.S.–Mexico divide,” Martinez said.

The institute, to be housed in the School of Transborder Studies, is also supported by Stephanie Fitzgerald, director and associate professor of American Indian Studies.

Pereira is in the process of applying to law school. She hopes to study Indian and intellectual property law at the Sandra Day O’Connor College of Law.

“I would hopefully see myself being an attorney, practicing tribal law, tribal governments and hopefully becoming chairwoman one day for my community,” said Pereira. “That's my goal. I'd love to be chairwoman for my community when we are federally recognized.”

Meghan Finnerty contributed to this story.

More Law, journalism and politics

Can elections results be counted quickly yet reliably?

Election results that are released as quickly as the public demands but are reliable enough to earn wide acceptance may not…

Spring break trip to Hawaiʻi provides insight into Indigenous law

A group of Arizona State University law students spent a week in Hawaiʻi for spring break. And while they did take in some of the…

LA journalists and officials gather to connect and salute fire coverage

Recognition of Los Angeles-area media coverage of the region’s January wildfires was the primary message as hundreds gathered at…