At the outset of the two-day Veterans in Society conference at Arizona State University’s Sandra Day O’Connor College of Law, moderator Bruce Pencek asked a question:

“What does it mean to be a veteran?”

Panelists at the event, which was hosted by the College of Integrative Science and Arts, attempted to answer that question Oct. 20–21 by looking at issues such as veterans’ resilience, the transition from military life to civilian life and how the arts can help veterans.

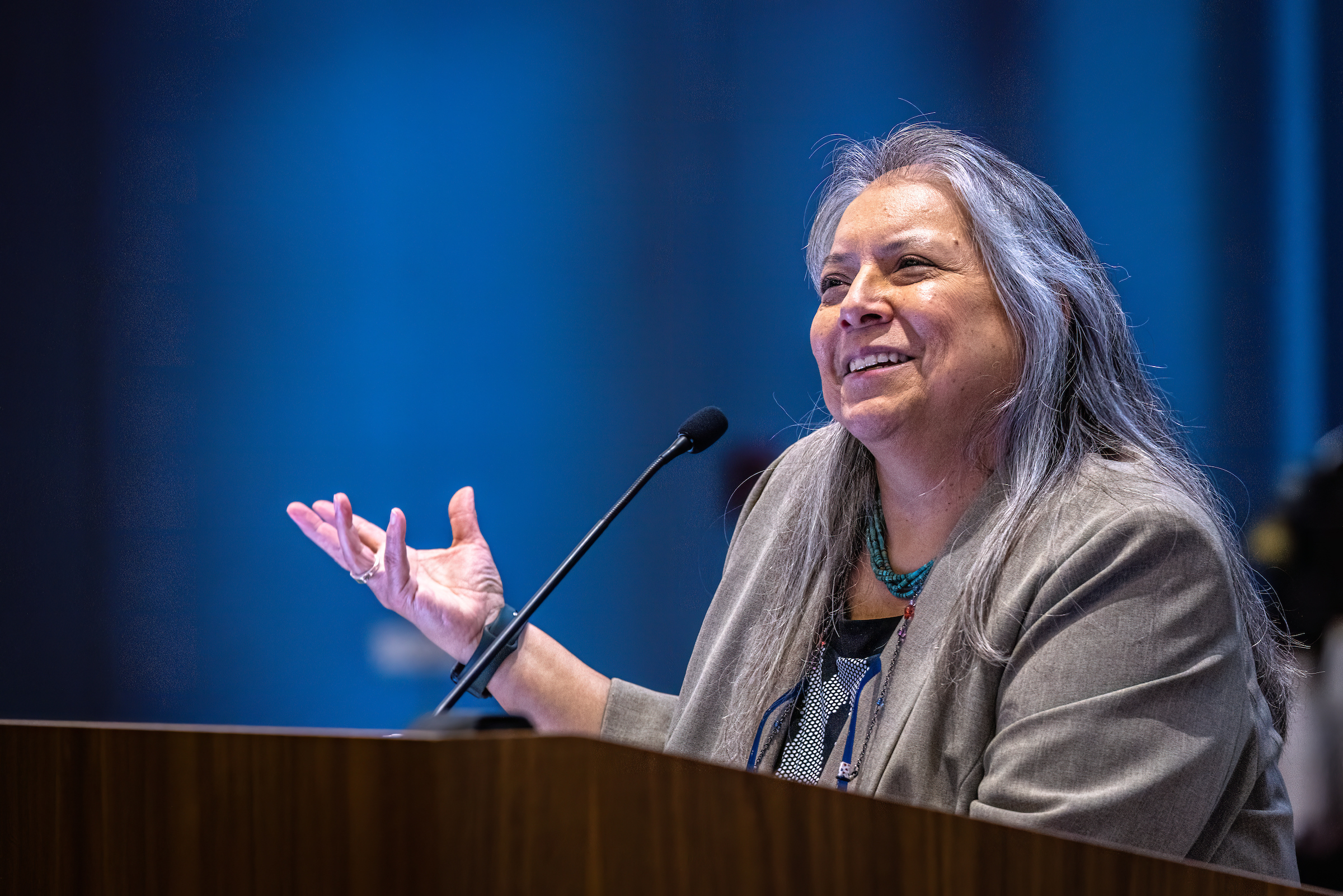

The keynote speaker for the event was Zonnie Gorman, a recognized historian on the original Navajo Code Talkers of World War II and the daughter of World War II Code Talker Carl Gorman.

'Veterans’ Transitions'

At the first panel discussion Thursday morning, the panelists discussed the difficulty veterans face when leaving the military and what more society can do to help that transition.

Bob Beard, a Marine Corps veteran and public engagement strategist for ASU's Center for Science and the Imagination, talked about the university's Veterans Imagination Project, which helps veterans project their future through the use of storytelling, futures thinking and collaborative imagination.

At the end of the project, the veterans — with the help of an artist — can clarify and envision their future in ways they never would have imagined.

“More than 200,000 men and women transition out of the military every year. For them, drastic change is not somewhere on the horizon. It’s instant,” Beard said. “The military world does a fantastic job training people to do the jobs they’re hired to do. But I believe the way out of the service is treated more like a simple job change and relocation. For veterans in the room, we know that can’t be further from the truth.”

Former military member and independent scholar Robert J. White conducted a study to find out why so many veterans leave their first jobs in civilian life within 24 months.

A 2014 study from VetAdvisor and the Institute for Veterans and Military Families at Syracuse University found that nearly half of all veterans leave their first post-military position within a year, and between 60% and 80% of veterans leave their first civilian jobs before their second work anniversary.

White said he left the Army to work for Shell Global in 2008. Fourteen other veterans made the same transition to Shell that year, but only two remained by 2010.

White said he found that veterans, in addition to feeling dissatisfied with typical job concerns like compensation, poor leadership and no clear path for promotion, also cited a loss of camaraderie, a lack of respect for veterans’ leadership experience and a lost sense of purpose.

White said it’s incumbent upon veterans to understand career ownership is their responsibility and that working for large companies can’t replace the camaraderie and sense of service they had in the military.

“I don’t know how camaraderie can be fulfilled in the corporate world,” White said. “I look for those experiences somewhere else. I’m not going to find my sense of purpose in corporate America.”

Code Talkers

Historian and expert on the original Navajo Code Talkers of World War II Zonnie Gorman delivers the keynote address for the fifth Veterans in Society conference on Thursday, Oct. 20, at the Beus Center for Law and Society on ASU's Downtown Phoenix campus. As the daughter of the oldest of the original Code Talkers, Carl Gorman, she spoke of her personal and academic knowledge of the first 29 Navajo Marine code creators. Photo by Charlie Leight/ASU News

During her keynote speech Thursday night, Gorman eloquently told the life story of two men who were part of the original 29 Code Talkers: Her father, Carl, and William D. Wilson.

The Code Talkers were made up of 29 Navajo men who created a code assigning a Navajo word to key phrases and military tactics. For example, in the code, a dive bomber became a “chicken hawk,” an observation plane became an “owl” and a fighter plane was a “hummingbird.”

“They were using Navajo words for words we didn’t have in our native language, like bombs and tanks,” Zonnie Gorman said. “They also developed a coded alphabet using sounds.”

How successful was the code? It remained unbroken through the end of the war, and during the nearly monthlong battle for Iwo Jima, six Navajo Code Talkers transmitted more than 800 messages without an error.

Gorman noted that the urge to serve was so strong for her dad and Wilson that they lied about their age to get into the Marines. Carl, who was 35 in 1942, said he was 25 on his application form. Wilson, who was a 15-year-old sheep herder, said he was 18.

All 29 Code Talkers graduated from boot camp; the dropout rate for other units was approximately 10%.

“These men were extremely patriotic,” Gorman said. “During World War II, Native Americans were the largest group to volunteer for service.”

That fact is remarkable, she said, because many Native American children, including Carl and Wilson, attended boarding schools that attempted to assimilate them into mainstream society, one method being prohibiting them from using their native language.

“Now, suddenly, the same government that was forbidding them to speak their language was now using their language to help American men win their freedom,” Gorman said. “The irony of this story is what resonates with a lot of people.

“To me, that’s what the Code Talkers represent. Their story connects with everyone. It’s a Navajo story, an American story, a military story and an international story. But, to me, it’s all about their resiliency as Diné people.”

Before Gorman spoke, retired Army Lt. Gen. Benjamin Freakley, now a professor of practice of leadership at ASU and a special advisor to President Michael Crow for leadership initiatives, said he was appreciative of the conference because it will help civilians better appreciate what veterans have endured.

"We have an increasing military-civilian gap," Freakley said. "Fewer and fewer people understand what the military is and what the military does. That's why this work is so critical."

Freakley said the perception of veterans as victims has to change.

"Let me assure you. They are not victims. They are victors," he said. "They did everything we asked them to do."

Retired Army Lt. Gen. Benjamin Freakley speaks at the Veterans in Society conference on Oct. 20 at the Beus Center for Law and Society on ASU's Downtown Phoenix campus. Photo by Charlie Leight/ASU News

'Resilience Among Veterans'

Friday morning, Rachel Larson, a lecturer in ASU’s College of Health Solutions, and Amanda Straus, a doctorate of behavioral health student at the College of Health Solutions, told the audience about an ongoing project titled “Veteran Resiliency Review” aimed at empowering veterans to take charge of their health in an effective way and reducing the suicide rate among veterans during their panel on "Resilience Among Veterans."

In Arizona, veterans account for more than 20% of all suicides while accounting for just 9% of the population.

Larson said the project works in coordination with the Arizona Coalition for Military Families and Be Connected, a support and resource group for Arizona veterans. With the help of the coalition, nominations of veterans in need are put forward. A review committee then chooses which cases to review with in-depth interviews.

Thus far, Straus said, 51 veterans have been nominated. Of those 51, 16 reported needs and requested assistance.

“Most veterans reported having only one need. Some had more than one need,” Straus said.

Once those needs are identified, the veterans are provided access to resources, whether it’s Be Connected or another group. And they’re not just handed a phone number. They are directly connected to a person who can provide either the support or resources they desire.

“Many veterans indicated they were unaware many of these resources were even available to them,” Larson said.

Larson said project organizers will do more interviews over the next few months to collect a larger sample. They will use the results to help implement programs targeted at specific needs, such as transportation, access to health care and food insecurity.

The power of arts and humanities

During a panel titled "Humanities and the Arts for Veteran Resilience," Alisha Ali, an associate professor in the Department of Applied Psychology at New York University, talked about a program called DE-CRUIT, which uses narration through theater – specifically, Shakespeare’s works — to help veterans heal from trauma, feel more connected to others and begin the process of forgiving themselves.

The panel was moderated by Jerome Clark, assistant professor in ASU's School of Humanities, Arts and Cultural Studies.

DE-CRUIT’s goal is to help veterans understand the emotions swirling inside them as they enter the civilian world. Shakespeare’s words help because many of the military characters of Shakespeare’s plays also dealt with the same terrors that modern-day veterans feel today.

The program has shown to reduce symptoms of post-traumatic stress and depression, produce greater self-efficacy, which then translates into greater confidence in themselves, and improve heart-rate variabilities, Ali said.

Here’s how the eight-week program works: Participants first practice and perform Shakespeare verses that eloquently describe the horrors of war. Then, each person writes his/her own personal “trauma monologue.” They’re asked to circle words that are emotional for them, a way to identify themes and help them find what Shakespearean monologue they’ll eventually perform.

In a key stage, the veterans hand off their trauma monologue to another participant, who then performs the monologue.

“I can perform something and not forgive myself,” Ali said. “But if it’s performed by a fellow veteran, I can understand from a distance that I need to forgive them, and that begins the process of forgiving myself.”

In the final stage, the veterans perform their trauma monologue — “It’s terrifying,” Ali said — and a Shakespearean monologue in front of family members and friends.

Often, the veterans will describe things in their trauma monologue that they have not expressed to those closest to them.

“They know they’ll be listened to, and they’ll be heard,” Ali said.

Top photo: Rashaad Thomas, a poet, writer, scholar and U.S. Air Force veteran from South Phoenix, reads one of his works as part of the introduction to the conference keynote address on Oct. 20. Photo by Charlie Leight/ASU News

More Health and medicine

The surprising role of gut infection in Alzheimer’s disease

Arizona State University and Banner Alzheimer’s Institute researchers, along with their collaborators, have discovered a surprising link between a chronic gut infection caused by a common virus and…

ASU, University of Wisconsin partner to empower Black people to quit smoking

Arizona State University faculty at the College of Health Solutions are teaming up with the University of Wisconsin to determine which treatments work best to empower Black people to quit…

New book highlights physician wellness, burnout solutions

Health care professionals dedicate their lives to helping others, but the personal toll of their work often remains hidden.A new book, "Physician Wellness and Resilience: Narrative Prompts to Address…