ASU math alumna models high-velocity impact for NASA's DART mission

ASU alum Wendy Caldwell.

History was made on Sept. 26 when NASA’s Double Asteroid Redirection Test (DART) successfully impacted its asteroid target, the agency’s first attempt to move an asteroid in space. As a part of NASA’s overall planetary defense strategy, DART’s impact with the asteroid demonstrated a viable mitigation technique for protecting the planet from an Earth-bound asteroid or comet, if one were discovered.

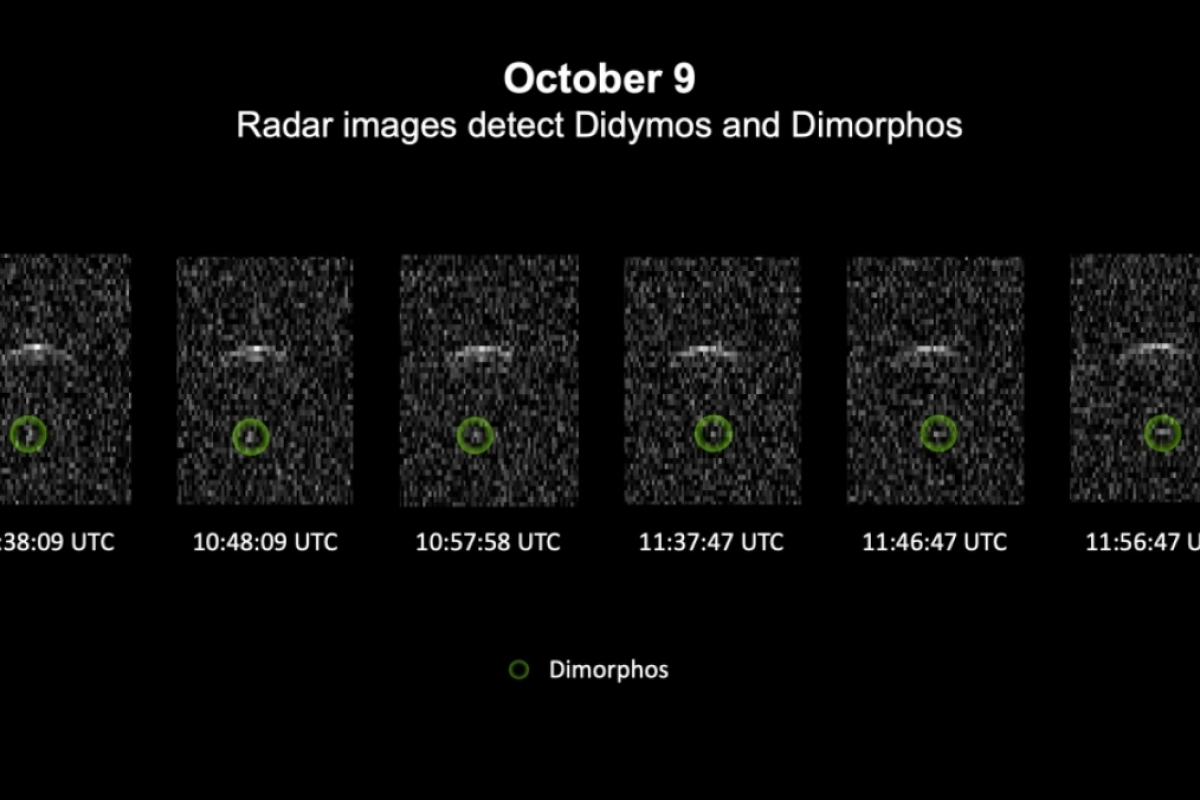

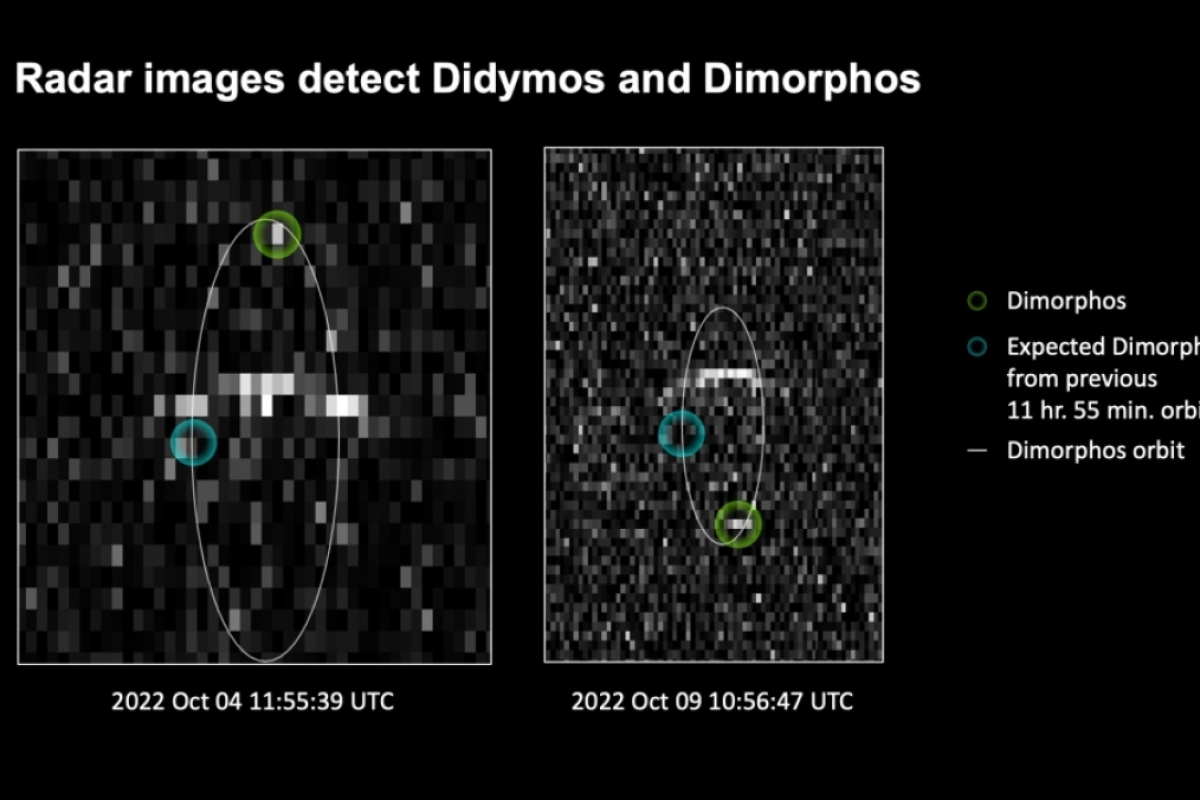

DART targeted the asteroid moonlet Dimorphos, a small body just 530 feet in diameter. It orbits a larger, 2,560-foot asteroid called Didymos. Neither asteroid poses a threat to Earth.

Wendy Caldwell is a scientist at Los Alamos National Laboratory and a member of DART’s Impact Modelers Working Group. She earned her PhD in applied mathematics from Arizona State University's School of Mathematical and Statistical Sciences in 2019.

Caldwell was at the watch party at Johns Hopkins Applied Physics Laboratory as the successful impact was announced at 7:14 p.m. EDT. Watching the monitors, Caldwell knew viewers would not actually see Dimorphos, the secondary, smaller asteroid of the Didymos system, until an hour before impact – with the world watching.

“When we saw it and got confirmation of ‘target locked,’ we were screaming and cheering like it was the Super Bowl!" Caldwell said. "It was even crazier when the screen went red at impact. I remember saying, ‘Look at that resolution’ as the spacecraft plunged closer to the surface of Dimorphos. We got some great views of surface boulders and other features. It was also validating for those of us who were hypothesizing that Dimorphos would be a rubble pile with regolith. Nailed it!”

The Impact Modelers Working Group is a collaborative effort across institutions for the DART mission, which includes two Los Alamos National Laboratory scientists, both women. The group worked on inverse tests in which they ran simulations to mimic data they would receive from the impact. Then they shared that data with other team members, who run simulations to try to determine properties, such as material composition and momentum enhancement.

Prior to spacecraft impact, Caldwell’s job on the “truth” team was to model high-velocity impacts into rocky targets to help inform likely material compositions of Dimorphos and to predict the momentum enhancement of the impact. Currently, her job is to model the impact given the data gathered from the mission, in order to better understand Dimorphos and deflection by kinetic impactor. Her team gets new data on a regular basis and is continually updating and improving the models.

She has also done benchmarking studies in the Los Alamos National Laboratory hydrocode FLAG. Her team published two papers in September, one on their predictions for the DART impact and one summarizing their inverse test and results.

Caldwell uses numerical partial differential equations and computational solid mechanics in her simulations. There are also post-processing calculations used for determining the amount of momentum imparted to Dimorphos from the impact, as well as the period change.

“Most of that stuff is vector calculus, but a lot of physics, like orbital mechanics, feature prominently,” Caldwell said.

A significant amount of computer power is needed to run the 3D impact simulations. Caldwell’s code is parallel and can run on up to 3,600 processors at a time. It can take days of run time on those processors for simulations to complete.

“It's a heavy lift, and not something that can be achieved on a laptop or even smaller supercomputers. Our LANLLos Alamos National Laboratory computers can run calculations on the order of 40 petaflops — that's 40 million billion floating point operations per second,” Caldwell said. “And people like me still whine about it not being fast enough.”

Analysis of data obtained over the past two weeks by NASA’s DART investigation team shows the spacecraft's kinetic impact with its target asteroid, Dimorphos, successfully altered the asteroid’s orbit. The new data provide some interesting information about both asteroid properties and the effectiveness of a kinetic impactor as a planetary defense technology.

“These data are going to allow us to validate our modeling techniques against impacts into space rocks big enough to pose a threat to life on Earth,” Caldwell said. “We don't have a lab for these experiments, so getting to actually do it in space was really cool.”

The DART team is a diverse group of scientists coming from a wide array of backgrounds. Caldwell explains what a scientist in 2022 might look like.

“A scientist looks like whoever is reading this. We are all born scientists — it is why kids ask ‘why?’ all the time. It is our nature to want to understand the world around us.

“Scientists are normal people. I have tattoos and piercings, usually dye my hair weird colors, dance, direct plays and perform in a local cabaret. And I'm still a scientist. Yes, I like to stay home and read books sometimes, but I also stood in line at Disney to meet Elsa and Anna.

“The thing is, you probably won't know if you see a scientist, because, contrary to how we are portrayed in popular culture, we don't stand out. Some of my colleagues wear suits every day. Some wear shorts and flip-flops. One of the greatest things about my job is that it doesn't matter at all how I look — it matters that I do good science.”

More Science and technology

Cracking the code of online computer science clubs

Experts believe that involvement in college clubs and organizations increases student retention and helps learners build valuable…

Consortium for Science, Policy & Outcomes celebrates 25 years

For Arizona State University's Consortium for Science, Policy & Outcomes (CSPO), recognizing the past is just as important as…

Hacking satellites to fix our oceans and shoot for the stars

By Preesha KumarFrom memory foam mattresses to the camera and GPS navigation on our phones, technology that was developed for…