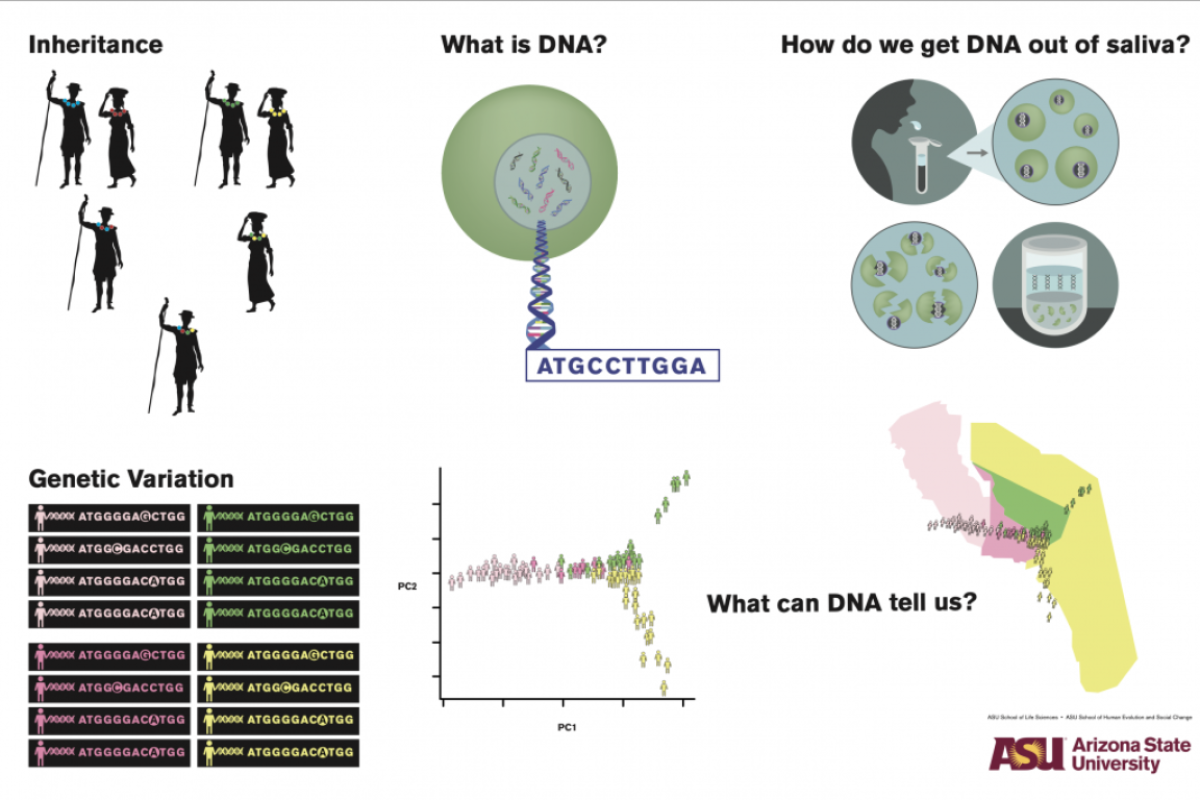

Genes, particular sequences of DNA, determine most of the characteristics that identify species worldwide. In humans, knowing why people differ from person to person has been a main question that scientists have asked. Investigating genetic variation within populations allows us to understand human evolution, migration patterns and even disease prevention and treatment.

Recently, a team of interdisciplinary researchers from Arizona State University investigated patterns of genetic variation in northern Kenya.

Associate Professor Melissa Wilson, Regents Professor Anne Stone, and former PhD student Angela Travella Oill and undergraduate student Emma Howell from the School of Life Sciences, joined Associate Professor Sarah Mathew and Carla Handley, a visiting scholar from the School of Human Evolution and Social Change.

The study was a multi-year collaborative effort briefly interrupted by the COVID-19 pandemic. However, the delay turned into an opportunity to expand on the communication channels already established over the course of the study to engage in additional outreach campaigns to raise awareness about COVID-19 among communities in the study area.

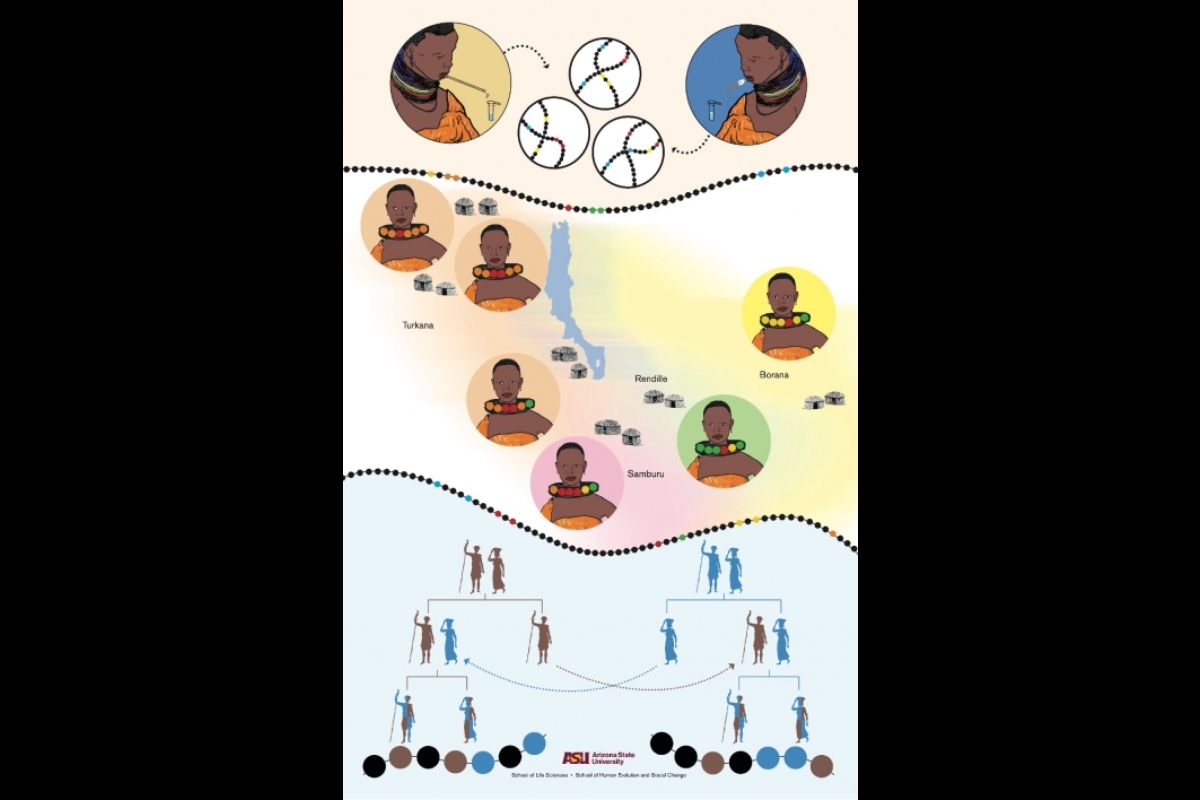

Their journey began in 2016. Mathew and Handley collected saliva samples and demographic information from 572 individuals in four neighboring regions: Tukana, Samburu, Wsa Borana and Rendile.

DNA was extracted from the saliva samples and after all data was gathered, Wilson and Stone supervised the sequencing, genotyping and analysis of the DNA samples, performed by recent graduate Oill, the first author of the study.

For the researchers, it was important to spread the word about the goals and methods of the study and share the results with the Kenyan community. The team worked with Jacob Sahertian, director of academic media for the ASU School of Life Sciences VisLab, to create graphics for an information campaign.

“I did additional research on the region through documentaries and studies to gather ideas for how best to communicate the information they requested,” Sahertian said.

He drew inspiration from photos from the region provided by the research team as well as additional sources, mirroring local signage and clothing styles to lend a personal touch to the campaign.

Then, in 2018, after data collection and analysis, Oill had the opportunity to travel to Kenya to share preliminary findings using the newly created visuals.

“People were glad we came and talked with them about the project. They thought the preliminary results were interesting," she said.

“Some people said that they now have a better understanding of why we collected spit from them. People also expressed their excitement about wanting to know what else we find from their DNA."

The results of the study, published earlier this year in the American Journal of Biological Anthropology, suggest that geographic distance, not culture, mainly shapes genetic variation within and among human groups in Northern Kenya. Because most people marry those who live nearby and don’t go far when they relocate, genes stay local, and thus genetic variation mostly depends on geographic location.

“The ethnolinguistic groups that have more intermarriage between them also have shown evidence of more genetic relatedness between them,” Wilson said.

Overall, the results highlight the importance of geography, even on a local scale, in shaping observed patterns of genetic variation in human populations.

“The history of people as told by genes is not the same as the history told by culture,” Mathew said. “This to me is one of the most interesting implications of these findings. The different stories these two pathways of transmission tell about humans hold the key to understanding the unique evolutionary trajectory of our species.”

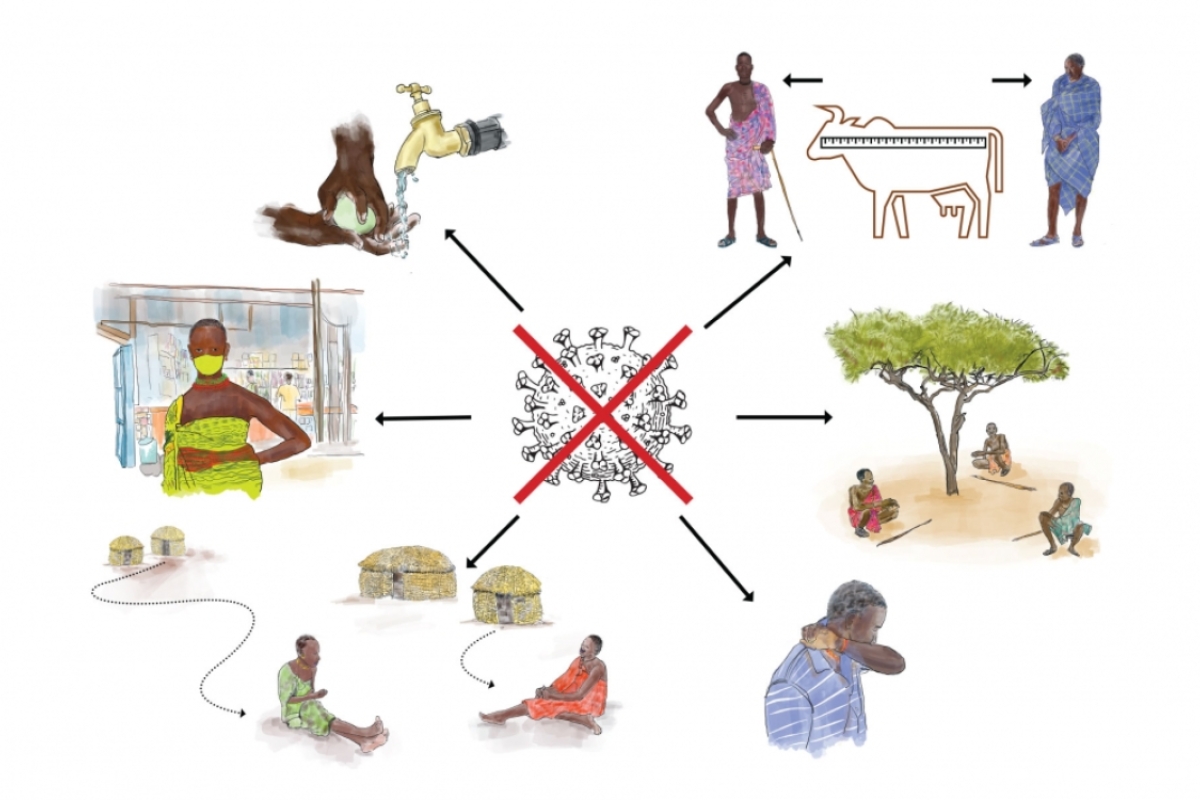

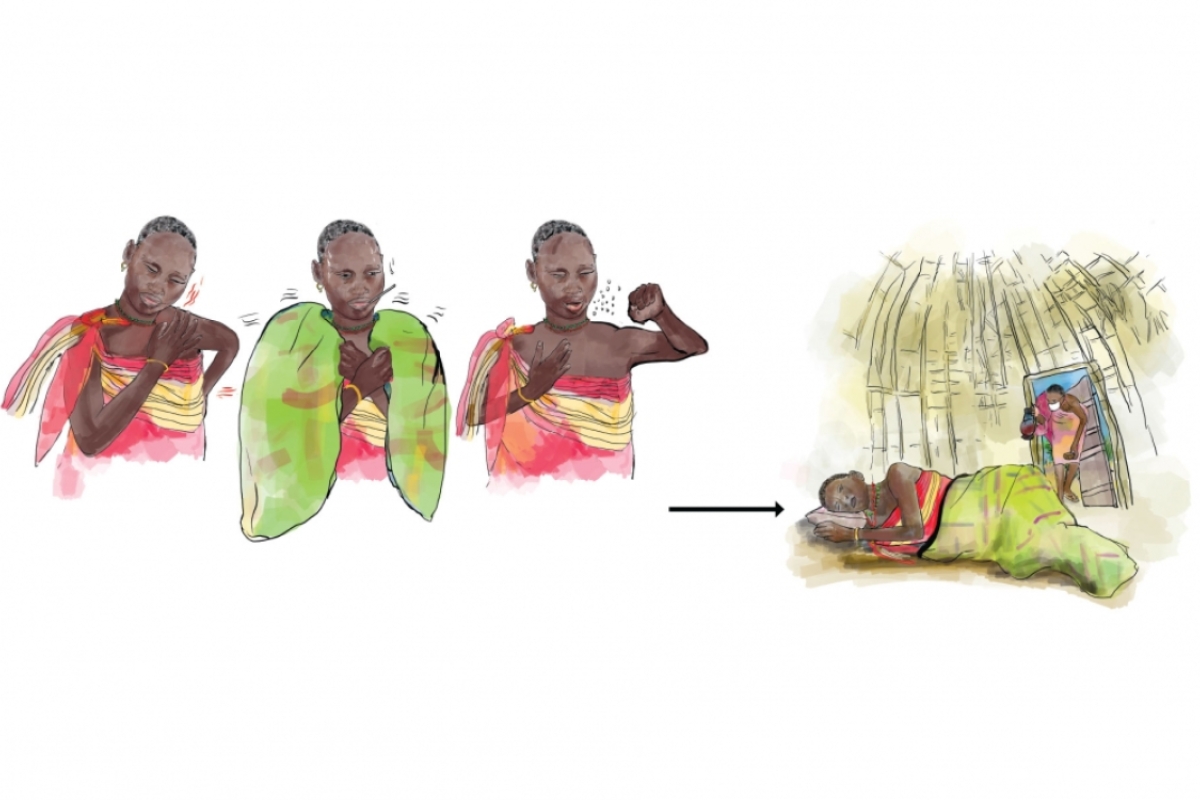

When research activities were interrupted by the COVID-19 pandemic in 2020, it was an opportunity for the investigators to leverage their ongoing relationships with the communities and help with the local COVID-19 response. They focused on creating and distributing educational campaigns in collaboration with the VisLab and with local research assistants in Kenya. Sahertian created visuals describing COVID-19 transmission and prevention strategies, but in a unique way catered for the Kenyan communities:

“We wanted to represent elements of their culture and day-to-day life. … (For example), people don’t carry rulers everywhere; they are herders, so we used a cow to represent distance. That is an easy visual representation,” Sahertian said.

The resulting graphics were printed on cloth, making them easier to fold, roll and travel from place to place with greater durability.

In addition to the visuals, and in order to reinforce this message, audio recordings in the local languages were spread via WhatsApp. Moreover, researchers worked with local women to make and distribute around 1,000 masks.

Altogether, the work done in northern Kenya is essential in understanding key aspects of genetic variation. Sharing research findings with study communities through outreach campaigns, not only on aspects of genetic research but also in regards to improving their health, is essential as we keep navigating the negative effects of COVID-19.

Now the team is undertaking a follow-up study to evaluate attitudes toward participating in genetics research and examine how dissemination changes these attitudes. They hope this new study will help develop community-informed best practices for genetics research in rural, non-literate populations.

Wilson is affiliated with the School of Life Sciences and Biodesign Center for Mechanisms of Evolution. Mathew and Stone are affiliated with the School of Human Evolution and Social Change and the Institute of Human Origins. All contributors are affiliated with the Center for Evolution and Medicine.

Top photo courtesy Sara Mathew

More Science and technology

Hack like you 'meme' it

What do pepperoni pizza, cat memes and an online dojo have in common?It turns out, these are all essential elements of a great cybersecurity hacking competition.And experts at Arizona State…

ASU professor breeds new tomato variety, the 'Desert Dew'

In an era defined by climate volatility and resource scarcity, researchers are developing crops that can survive — and thrive — under pressure.One such innovation is the newly released tomato variety…

Science meets play: ASU researcher makes developmental science hands-on for families

On a Friday morning at the Edna Vihel Arts Center in Tempe, toddlers dip paint brushes into bright colors, decorating paper fish. Nearby, children chase bubbles and move to music, while…