Editor's note: This story originally appeared in the fall 2022 issue of ASU Thrive magazine.

As the sunniest city in the U.S., Phoenix has long been at the forefront of the solar revolution. Today, more than 190,000 solar installations, many of them in the Valley, provide nearly 10% of the state’s electricity. The energy from these solar panels coupled with the electricity from nuclear, hydropower and wind installations generate more than 50% of Arizona’s electricity.

This is promising, and for Arizonans, furthering this clean-energy transition in partnership with numerous stakeholders presents a historic opportunity to remake the economy in a way that benefits everyone, including businesses, residents, rural areas and the most vulnerable communities.

“There’s virtually no disagreement in Arizona that we need to decarbonize,” says Gary Dirks, senior director of the Julie Ann Wrigley Global Futures Laboratory. “The issue is how to go about doing it. As we’re making this transformation toward renewable energy and phasing out fossil fuels, we have to get it right.”

Building an energy supergroup

Dirks directs LightWorks, a multidisciplinary effort within the Global Futures Laboratory to solve energy challenges. He helps orchestrate programs at ASU that bring together researchers across multiple disciplines including the social sciences, policymakers, business leaders and community leaders to address pressing climate issues. These collaborations, Dirks says, are absolutely key.

“This energy transformation is going to take deep relationship building,” Dirks says. “We also need to be more purposeful about including all sectors and disciplines, especially social scientists who can help think about how we can evolve our political and societal will to change policies and our behavior. This framework is crucial for creating a successful transition.”

He points to the urgent need for an “us” mindset in order to make the transition to a carbon-neutral economy equitable, to bring along people who are most vulnerable to energy shortages, and to bring along those whose jobs will change during the transition.

That’s why LightWorks “assembles teams that can approach these problems and challenges in a more comprehensive way than they are frequently addressed,” Dirks says. This includes emphasizing policy and social justice.

For instance, Dirks says, “We cannot leave people behind as we transform the energy system. We need to be especially attentive to communities hard hit by plant closures, and rural and Indigenous communities.”

It also requires creating strategically designed technologies to overcome some of the biggest challenges with current renewable energies. Those technology challenges are among other key areas of LightWorks’ focus.

“We need to be especially attentive to communities hard hit by plant closures, and rural and Indigenous communities.”

— Gary Dirks, senior director, ASU Global Futures Laboratory

Solving energy gaps

Clean hydrogen is a promising solution to two of renewable energy’s challenges. Those challenges are that solar power is naturally intermittent — and currently available storage technologies such as batteries are ill-equipped to store energy at large scales for more than a few hours. A second challenge is that achieving deep decarbonization will require an alternative source of fuel to displace the natural gas and oil that power many vehicles and industrial processes. Batteries will get better, but we need the hydrogen option in our toolkit, Dirks says.

Hydrogen is the most abundant element in the universe and a fuel source that produces no carbon emissions. While the clean hydrogen economy has been promised for decades, it has failed to materialize due to several technological and economic hurdles. But Ellen B. Stechel, the co-director of LightWorks, a senior global futures scientist and a professor of practice in the School of Molecular Sciences, believes hydrogen’s time has come.

Stechel is the director of the recently established Center for an Arizona Carbon-Neutral Economy, a coalition founded by Arizona Public Service, Salt River Project, Tucson Electric Power, Southwest Gas, ASU, The University of Arizona and Northern Arizona University. AzCaNE, which is housed within the Global Futures Laboratory, is joined by the Arizona Commerce Authority and many other stakeholders, including businesses and cities, and is in conversation with tribal communities.

“Our goal is to reach a carbon-neutral economy, but since there will be support from the Infrastructure Investment and Jobs Act, our first focus is clean hydrogen,” Stechel says.

Stechel’s vision for the future is one where Arizona produces more than enough clean hydrogen to meet its own needs, which would shift the state’s energy balance and turn it into a net energy exporter. This revolutionary shift would simultaneously decrease the state’s carbon emissions, foster technological innovation and save nearly $1 billion annually that Arizona spends importing fossil fuels from other states.

While this vision would have seemed outlandish only a few years ago, the work of Stechel and her collaborators at AzCaNE is bolstered by the U.S. Department of Energy’s $8 billion initiative to establish a network of regional clean hydrogen hubs across the country. If Stechel gets her way, one of those hydrogen hubs will be based in Arizona or established through a partnership with a neighboring state.

“These kinds of transitions aren’t easy,” Stechel says. “Arizona is a leader in the way we’re starting to pull everybody together behind this cause because unprecedented levels of cooperation will be necessary to succeed.”

A major part of AzCaNE’s work is collaborating with researchers, utilities and other stakeholders to find ways to dramatically lower the cost of hydrogen production to make it cost competitive with fossil fuels. For Stechel, this means creating future-forward technologies that scale. One of the more notable examples of this kind of technology is being developed by Ivan Ermanoski, a research professor at LightWorks and the School of Sustainability, and a senior global futures scientist, in a highly collaborative project for which Stechel serves as the principal investigator.

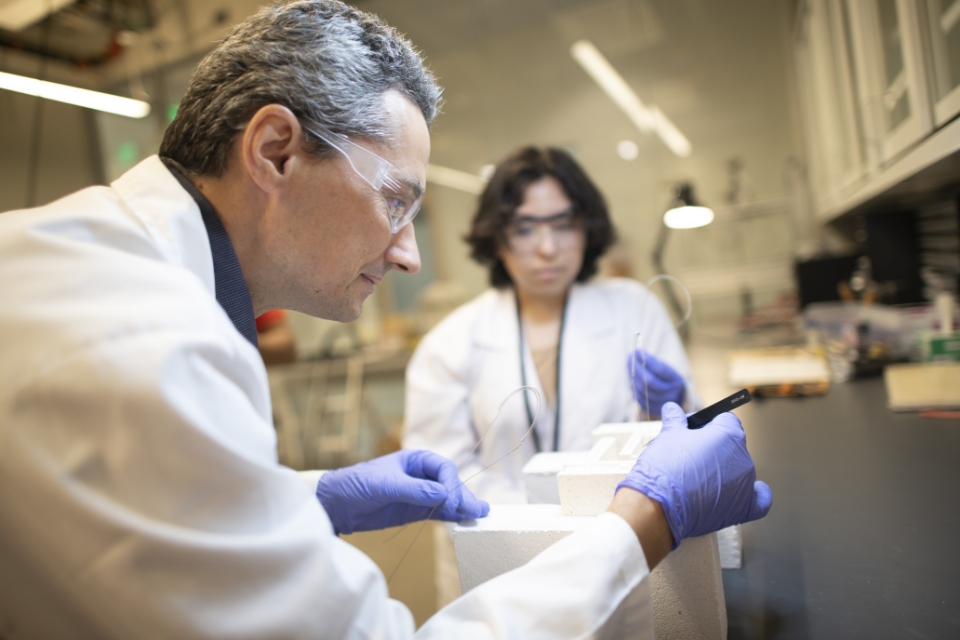

Ivan Ermanoski and Natalie Figueroa, an engineering and physics student, are excited about helping make clean hydrogen a reality. When hydrogen is burned as a fuel, it becomes water. Photo by Sabira Madady

Today, the U.S. produces an enormous amount of hydrogen, but nearly all of this hydrogen is created by using high-temperature steam to separate it from natural gas, and much of it is then used in refining fossil fuels. To break this cycle, Ermanoski and his colleagues have built a reactor that can use heat from the sun — collected, for example, by arrays of mirrors that concentrate sunlight onto a small area — to produce clean hydrogen.

A grant from the U.S. Department of Energy is sponsoring the development of Ermanoski’s functioning tabletop thermochemical hydrogen reactor, and it points to a future where a large-scale version of the device could be used to produce hydrogen that can provide Arizona residents and others in the U.S. with a clean and reliable source of energy on demand.

“When you don’t have renewable power, you have to get energy from somewhere else, and right now, that’s almost always coal or natural gas. The promise here is that hydrogen will have more uses in the future as a long-term energy storage solution,” Ermanoski says, “as well as to power numerous processes instead of fossil fuels.”

Better solar cells

The work being done at ASU on hydrogen technologies will play a vital role in the energy transition. Yet, although the costs of solar photovoltaics energy production fell by 82% from 2010 to 2019, there is still more innovation needed to make solar power technologies even cheaper and more efficient.

A pioneer in improving solar energy conversion efficiency is Zhengshan Yu, an assistant research professor in the School of Electrical, Computer and Energy Engineering and founder of the startup Beyond Silicon. Yu’s work focuses on improving conventional solar silicon panels by adding other semiconductor materials. Today’s silicon panels make up about 95% of the market and are about 20% efficient. So far, Yu and his team have created solar cells that are 28.6% efficient by using perovskite — which consists of materials that use the same crystal structure as calcium titanium oxide — on top of the silicon, which enables more efficient use of different colors of light, Yu says.

The company won $200,000 in the DOE Perovskite Startup Prize to commercialize these new, innovative perovskite/silicon tandem solar cells that can eventually be manufactured in the United States.

“Our goal is to propel this technology out of the lab and power the world,” Yu says.

Zhengshan Yu’s team has improved solar panel efficiency from 20% to 28.6% by adding other semiconductor materials on top of the silicon. Photo by Ghassan Al Balushi

Another leader in boosting solar efficiency and reducing costs is Arthur Onno, an assistant research professor in the School of Electrical, Computer and Energy Engineering.

He is working on a DOE-funded project that could revolutionize solar panels by using cadmium telluride, which proves significantly cheaper than silicon panels. Still, because of their lower efficiency, these “CadTel” panels only represent about 5% of the global market.

If more efficient, CadTel panels could capture a larger market share and significantly drive down the cost of solar energy. However, while researchers have known that CadTel has a relatively high theoretical efficiency, achieving this in practice has been challenging. A big hurdle is that solar cell manufacturers and researchers lacked a robust way to conduct tests of CadTel solar cells, which are around 50 times thinner than silicon cells.

“If you look at the basic physics, CadTel should be more efficient,” Onno says. “We just haven’t understood how to unlock the material’s potential.”

To overcome this problem, Onno and his colleagues developed a new type of solar cell probe that uses lasers rather than electricity to explore the performance of CadTel cells to tease out causes of inefficiency. Over the past year, the ASU researchers have delivered a handful of these devices to two U.S. solar manufacturers, which have begun using them in their industrial labs to work on improving CadTel solar panel efficiency.

“From the feedback we’ve received, our tools have been heavily used by the manufacturers,” Onno says.

“Our goal is to propel this technology out of the lab and power the world.”

— Zhengshan Yu, assistant research professor, School of Electrical, Computer and Energy Engineering

Microalgae with a big impact

Another approach to deep decarbonization is underway in the most unlikely of places — the city of Mesa’s wastewater treatment plant. For the past year, Bruce Rittmann, director of the Biodesign Institute's Swette Center for Environmental Biotechnology and a distinguished global futures scientist, has led a research project at Mesa’s wastewater plant focused on finding more effective ways to feed carbon dioxide to microalgae. These photosynthetic microorganisms thrive on CO2 and sunlight, and when they’re harvested, they can be cooked down into a carbon-neutral biofuel comparable to natural gas.

Treating wastewater in “anaerobic digesters” generates a substantial amount of greenhouse gas emissions in the form of CO2 and methane, which Rittmann realized could be harnessed to grow large amounts of microalgae. This process would, in effect, use microalgae to turn sunlight into a sustainable biofuel, but this requires the ability to separate the CO2 and methane efficiently. To solve this problem, Rittmann and his team developed a material made of tiny hollow fibers that can be placed in nearby pools to selectively deliver CO2 to microalgae growing in the ponds and capture a relatively pure source of methane to be used in a variety of industrial processes.

“If treatment plants harvest the methane and turn it into electricity, they can become energy neutral, and Arizona could produce enough methane to become an energy exporter,” Rittmann says. “This would have a huge impact on treatment plants, cities in Arizona, and the world.”

Scaling the use of the sun to grow microalgae for a biofuel could help fill in energy gaps. Photo by Deanna Dent

Decarbonization for a healthier planet

In addition to these technologies and while working on the social and behavioral aspects of the transition, ASU is developing and scaling other technological solutions toward a carbon-neutral economy, including carbon capture, water conservation, better battery storage, more resilient electrical grids, ways of approaching agriculture that improve soil and lower carbon emissions — and many more. The goal is to build a carbon-neutral economy that benefits all Arizonans.

“We have to come together with an inclusive mindset, not an us vs. them approach, to pave the path toward the economy and planet we all want to see,” Dirks says.

5 ways to help with the energy transition

Continue your education about the climate crisis and energy transition. Take free courses through asuforyou.asu.edu like Sustainable Earth and read the ASU report "Pathways to a Carbon-Neutral Arizona Economy.”

Get familiar with how energy decisions are made in your community. Advocate for the energy transition in your homeowner association, your company, your city, your circles and community organizations, and with politicians. Vote for what is important to you on energy.

Weatherize your home to lower your energy use. Learn more at energy.gov/energysaver/weatherize.

Consider rooftop or community solar. Visit your utility’s website to learn more.

If you’re looking to upgrade your vehicle, run the numbers on an electric car. It’s being adopted by many Phoenix residents, who own 42,000 electric vehicles, often powered by rooftop solar or Phoenix’s 570 public EV charging stations, according to a 2021 report by AZ Big Media.

Story by Daniel Oberhaus, a staff writer at Wired magazine and the author of “Extraterrestrial Languages” (the MIT Press). He is an ASU alumnus, ’15 BA in English (creative writing) and philosophy, and a graduate of Barrett, The Honors College.

Top image: A critical part of the energy transition is bringing everyone along, and that vision drives technology development, such as improvements to solar panels, microalgae grown from the sun for a biofuel and clean hydrogen. From left: Highly efficient solar electricity, scalable hydrogen reactors, carbon-neutral algae biofuel.

More Science and technology

Cracking the code of online computer science clubs

Experts believe that involvement in college clubs and organizations increases student retention and helps learners build valuable social relationships. There are tons of such clubs on ASU's campuses…

Consortium for Science, Policy & Outcomes celebrates 25 years

For Arizona State University's Consortium for Science, Policy & Outcomes (CSPO), recognizing the past is just as important as designing the future. The consortium marked 25 years in Washington, D…

Hacking satellites to fix our oceans and shoot for the stars

By Preesha KumarFrom memory foam mattresses to the camera and GPS navigation on our phones, technology that was developed for space applications enhances our everyday lives on Earth. In fact, Chris…