The steel gray muzzle of a military police officer’s machine gun pointed at her mother’s head as Nicole Anderson, then age 11, and her two sisters, ages 8 and 5, huddled in the back seat of a blue Fiat in terror.

After a carefree day of swimming and sunbathing on the white sandy shore along the Paraná River in La Paz, Argentina, Anderson’s mother had started driving home, still wearing a bikini — a freedom she’d taken for granted living in Australia. But personal freedom was a thing of the past after a right-wing coup overthrew the Argentine government in 1976.

Struggling to keep her hands steady, Anderson’s mother handed the officer her Australian passport. “Stay quiet!” she urged her daughters during the tense two hours it took for military police to confirm her identity with the Australian consulate and grant permission for the family to drive home.

The daughter of an Australian diplomat, Anderson grew up in war-torn countries where governments were toppled by military coups. As a result, she brings a deep passion for democracy and civil rights to her role as director of Arizona State University’s Institute for Humanities Research. At a time when eight in 10 registered voters on both sides of the political aisle fear that U.S. democracy could failAccording to a USA Today and Suffolk University survey., she shares voters’ fears — and is taking action to preserve democracy.

“I know firsthand what it’s like to live in undemocratic countries,” says Anderson, who spent her early childhood in Greece following the military coup in 1967 before moving to Argentina in 1974. “The impact on citizens is beyond what many people can imagine. It takes away all your freedoms. It takes away your voice to change things. There’s rule by fear and literally blood in the streets.”

Making voices heard

Anderson has launched “The Futures of Democracy” podcast with co-host Julian Knowles, professor of media and music, and chair of media and communications at Macquarie University in Sydney, Australia. The Arizona PBS podcast series poses the question, “Is democracy in crisis, or are we just at a turning point?”

Anderson and Knowles interview world-renowned experts and raise big questions surrounding democracy in the 21st century. In the series’ first podcast, ASU President Michael M. Crow discusses what role our education system plays in strengthening our democracy and whether democracy and citizenship should be taught as part of formal education.

In another episode, Kate Crawford, author of “Atlas of AI” and one of the world’s leading experts on the social, political and material aspects of artificial intelligence, discusses how AI and algorithmic decision-making systems impact the human rights of citizens and reinforce social inequality. The episode explores whether AI shapes our perceptions of reality and if this is a democratic problem.

As Americans await the next round of hearings investigating the Jan. 6 attack on the U.S. Capitol, these kinds of discussions are especially timely.

“Now is the right time to start talking about what is important about democracy and thinking through what it means to live in a democratic society,” Anderson says. “I’m trying to get people to think about the society they live in and the society they want to live in.”

As Anderson knows firsthand, democracy — and all its freedoms Americans hold dear — can disappear in a flash.

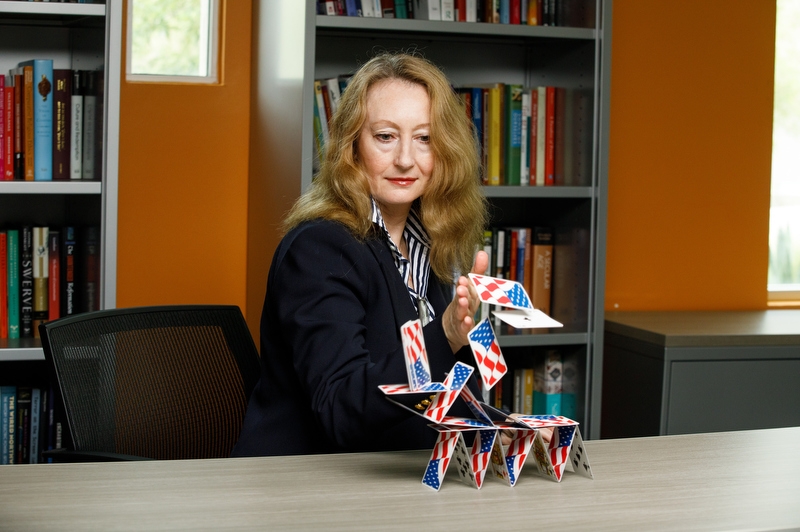

“I know firsthand what it’s like to live in undemocratic countries,” says Nicole Anderson, director of The Institute for Humanities Research at ASU. Anderson spent her early childhood in Greece following the military coup in 1967 before moving to Argentina in 1974. Photo by Andy DeLisle/ASU

April 21, 1967: A military coup d’état in Greece

Just weeks before scheduled elections, a group of right-wing army officers quickly seized power in Greece in a coup d’état. The coup leaders gained complete control of Athens by placing military tanks in strategic positions in the city. They dispatched mobile units to arrest leading politicians, authority figures and ordinary citizens suspected of left-wing sympathies using detailed lists prepared in advance. All told, an estimated 8,000 people were arrested in the first month of the coup, according to Amnesty International.

Longstanding political freedoms and civil liberties the Greeks had enjoyed and taken for granted for decades abruptly came to an end. Citizens lived in extreme fear, knowing they could be arrested without warrant at any time and brought before a military court to be tried.

Anderson was too young to remember life in Greece, but recalls stories her father shared about working in the country as an immigration officer, helping Greek people reclaim their personal freedoms by migrating to Australia, which has a large Greek population today.

March 24, 1976: Right-wing military coup in Argentina

Shortly before 1 a.m. on March 24, 1976, President Isabel Peron was detained by military officers, the opening act in the state of siege. As the day progressed, hundreds of workers, unionists, students and political activists were abducted from their homes, their workplaces or the streets. Congress was disbanded, with senators, deputies and staff members arrested, brutally beaten and thrown out the doors and windows of the Congressional Palace. As Argentina’s military dictatorship waged the so-called dirty war against its opponents, tens of thousands of people suspected of being dissidents or subversives were kidnapped, tortured or killed.

One night Anderson’s father didn’t come home from an evening at the pub with fellow Australian diplomats, and her mother feared for the worst. The diplomats had left their passports at the office and were detained by military police for 24 hours on their way home. The police pointed machine guns at them and forced them to stand against a wall until they could prove who they were.

Anderson can never forget the sound of bombs exploding in and near Acassuso, the Buenos Aires suburb where her family lived. Ever watchful for his family’s safety, Anderson’s father used a mirror attached to a long pole to examine the underbelly of their car to check for hidden bombs before they drove away.

“We heard bombs going off at night, shaking the house and waking us up,” recalls Anderson, who couldn’t go to school for two years as an adolescent because it was too dangerous.

Those two years became formative. She read voraciously, and her love of literature and philosophy blossomed. She felt an inner urge to do something with her life to work toward social justice and help others. Beginning at age 13, she started writing essays about social conditions after seeing the injustice all around her during the volatile time abroad.

“I’d write about materialism. I’d write about community. I’d write about what it means to be an individual — a whole range of philosophical questions I was constantly asking myself because I was confronted with the trauma of what was happening in different countries,” she says.

Protecting the future of democracy

Today, as director of ASU’s Institute for Humanities Research, she sees humanities as a powerful tool for social change and protecting democracy as a responsibility for all.

“Part of what the humanities can do is turn the facts into compelling stories that need to be told and influence and change the way people view the world,” she says.

“It is the small stuff that corrodes democracy: corruption, disregard for the Constitution, practicing autocracy within institutions, lack of education about democracy and its importance for freedom of speech, human rights, and above all, for access to voting,” she adds. “These things can corrode slowly, so it is vigilance of voting, of having your say and holding to account the governments we vote in that will enable the survival of democracy.”

Learn more about the Institute for Humanities Research.

Listen to “The Futures of Democracy” podcast.

Top photo: Nicole Anderson, director of The Institute for Humanities Research at Arizona State University. Photo by Andy DeLisle/ASU

More Law, journalism and politics

Can elections results be counted quickly yet reliably?

Election results that are released as quickly as the public demands but are reliable enough to earn wide acceptance may not always be possible.At least that's what a bipartisan panel of elections…

Spring break trip to Hawaiʻi provides insight into Indigenous law

A group of Arizona State University law students spent a week in Hawaiʻi for spring break. And while they did take in some of the sites, sounds and tastes of the tropical destination, the trip…

LA journalists and officials gather to connect and salute fire coverage

Recognition of Los Angeles-area media coverage of the region’s January wildfires was the primary message as hundreds gathered at ASU California Center Broadway for an annual convening of journalists…