ASU anthropologists design new ways to reduce stigma in global health care

ASU President's Professors Alexandra Brewis (left) and Amber Wutich. Photo courtesy Tim Trumble Photography

People who are large-bodied have no self-control. People with mental health conditions can’t be productive members of society. People who don’t use toilets are disgusting.

These are all stigmas Arizona State University anthropologists and President’s Professors Alexandra Brewis and Amber Wutich have observed over and over from different health professionals over many years.

Brewis and Wutich have spent many years identifying stigmas within health care practices across the world. Through global health classes, online trainings and an award-winning book, the professors are bringing attention to an often overlooked but solvable problem.

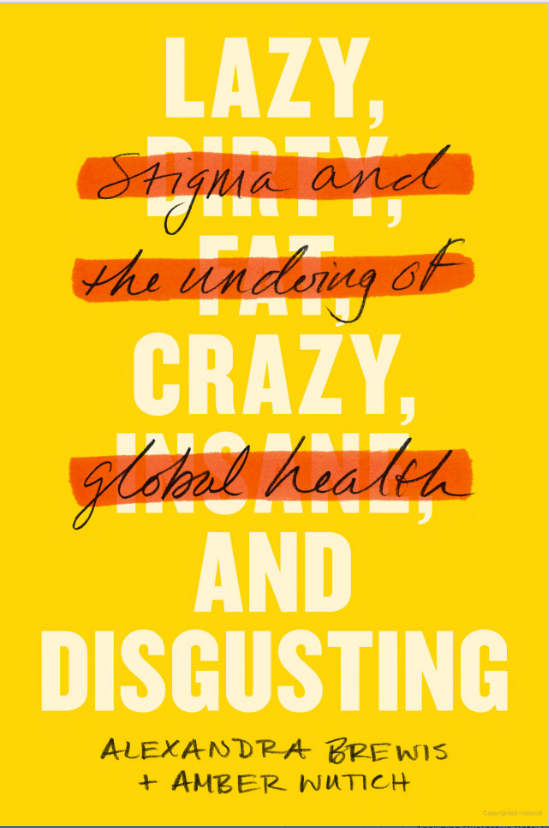

Their recent book “Lazy, Crazy, and Disgusting: Stigma and the Undoing of Global Health,” is based on their 50 years of combined fieldwork as medical anthropologists. Over the last decade, Brewis studied weight and issues around weight stigma in clinical settings, while Wutich has focused on people’s experiences of living with inadequate sanitation in places like South America and the U.S.-Mexico border.

“After doing fieldwork on an array of stigmatized issues over many years — like water insecurity, high body weight and ADHD — I came to understand that self-stigma, when we judge ourselves harshly and believe and agree with the negative values, is one of the more emotionally painful things that people endure,” Brewis said, a biocultural anthropologist with ASU’s School of Human Evolution and Social Change.

“This is why we think it is so important to address any aspect of health care that might — even inadvertently — be contributing to that profound human pain,” she said.

Brewis said what is most concerning is when doctors contribute to the pain patients are already enduring from self-stigma. For example, she said people with large bodies sometimes avoid going to the doctor’s office because they anticipate poor treatment.

“Stigmas also tend to beget other stigmas,” Brewis said. “We sometimes refer to this as intersecting or layered stigmas — it is easier to pile stigma onto people already classified as less human than others, whether on the basis of racialized categories, gender identity, poverty, migrant status and so on.”

Cover courtesy Johns Hopkins University Press, Baltimore. Cover design by Kelley Galbreath

The book is a continuation of the work the professors do at the Center for Global Health and the Culture, Health, and Environment Laboratory in the School of Human Evolution and Social Change. In the lab, undergraduate and graduate students are involved in their data collection and analysis, with collaborators at many different sites all around the world.

“Other related team projects with a similar purpose of improving health globally are looking at the emotional and health consequences of lack of access to clean and adequate water, and working with engineers to design better solutions for low-resource communities,” Brewis said.

Along with the book and lab experiences, Brewis and Wutich both teach courses like Poverty and Global Health (ASB 305). Students learn how poverty shapes health risks and how stigma ultimately promotes illness and poverty as part of the school's global health degree programs. The global health program has options for bachelor's, master's and accelerated 4+1 degree programs.

“This is one of the things that makes the way we study global health of great value: the ability to turn tables and consider — and rectify — and identify how global health efforts in themselves might inadvertently be part of the problem, even while people practicing it believe they are ‘doing good,’” Brewis said. “This ability to be more reflective to improve how we work is one of the core benefits that anthropology brings to the table. Global health as a field has a particular responsibility to be ethical and impactful in the broad sense, as well as a narrow one. Anthropology is central to gaining that wider lens.”

Brewis and Wutich have gone beyond the book and classroom to find practical ways to reduce stigma in global health care, including last year's training around stigma reduction for Centers for Disease Control management. The one-hour “Recognizing and Challenging Stigma” self-paced online course they developed for health professionals is, says Brewis, a great tool for those who want an accessible overview of the book’s recommendations about how health professionals can recognize and avoid promoting stigma through their work.

“Lazy, Crazy, and Disgusting: Stigma and the Undoing of Global Health” has won numerous awards, including the 2022 Human Biology Association Book Award; the 2020 Carol R. Ember Book Prize from the Society for Anthropological Sciences; and was a finalist for the 2020 Book of the Year Award from the British Sociology Association/Foundation for the Sociology of Health and Illness.

More Health and medicine

College of Health Solutions launches first-of-its-kind diagnostics industry partnership to train the workforce of tomorrow

From 2007 to 2022, cytotechnology certification examinees diminished from 246 to 109 per year. With only 19 programs in the…

ASU's Roybal Center aims to give older adults experiencing cognitive decline more independence

For older people living alone and suffering from cognitive decline, life can be an unsettling and sometimes scary experience.…

Dynamic data duo advances health research

The latest health research promises futuristic treatments, from cancer vaccines to bioengineered organs for transplants…