A sharper image for proteins

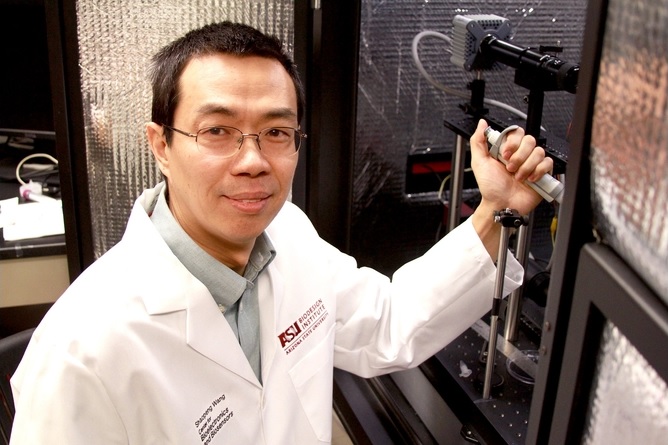

This graphic shows the experimental setup for performing evanescent scattering microscopy. The technique is a label-free method for sensitive imaging of biomolecules, including proteins. A beam of laser light is directed at a molecular sample with the proper angle to produce a condition known as total internal reflection. The resulting evanescent wave can excite the molecules at the glass-liquid interface, allowing for exceptionally precise imaging.

Proteins may be the most important and varied biomolecules within living systems. These strings of amino acids, assuming complex three-dimensional forms, are essential for the growth and maintenance of tissue, the initiation of thousands of biochemical reactions, and protecting the body from pathogens through the immune system. They play a central role in health and disease, and they are primary targets for pharmaceutical drugs.

To fully understand proteins and their myriad functions, researchers have developed sophisticated means to see and study them through advanced microscopy, improving light detection, imaging software and the integration of advanced hardware systems.

In a new study, corresponding author Shaopeng Wang and his colleagues at Arizona State University describe a new technique that promises to revolutionize the imaging of proteins and other vital biomolecules, allowing these tiny entities to be visualized with unprecedented clarity and by simpler means than existing methods.

"The method we report in this study uses normal cover glass instead of gold-coated cover glass, which has two advantages over our previously reported label-free, single-protein imaging method," Wang says. "It is compatible with fluorescence imaging for in situ cross validation, and it reduces the light-induced heating effect that could harm the biological samples. Pengfei Zhang, an outstanding postdoctoral researcher in my group, is the technical lead of this project."

Wang has a joint faculty position in the Biodesign Center for Bioelectronics and Biosensors and School of Biological and Health Systems Engineering. The group’s research findings appear in the current issue of the journal Nature Communications.

The new method, known as evanescent scattering microscopy (ESM), is based on an optical property first recognized in antiquity, known as total internal reflection. This occurs when light passes from a high-refractive medium (like glass) into a low-refractive medium (like water).

When the angle of incident light is moved away from the perpendicular (relative to the surface), it eventually reaches the “critical angle,” resulting in all the incident light being reflected, rather than passing through the second medium. (To properly illuminate biological samples, laser light is used.)

Shaopeng Wang is a researcher in the Biodesign Center for Bioelectronics and Biosensors and the School of Biological and Health Systems Engineering at ASU.

Total internal reflection produces an evanescent field, which can excite cells or molecules like proteins at the glass-water interface, when such molecules are affixed to a cover glass, allowing researchers to visualize them in startling detail.

Previous methods commonly label the biomolecules of interest with fluorescent tags known as fluorophores, to better image them. This process can interfere with the subtle interactions being observed and requires cumbersome sample preparation. The ESM technique is a label-free imaging method requiring no fluorescent dye or gold coating for sample slides.

Instead, the method exploits subtle irregularities in the surface of the cover glass to produce images of razor-sharp contrast. This is achieved by imaging the interference of evanescent light scattered by the single-molecule samples and the rough texture of the cover glass.

The use of evanescent wave scattering allows samples, including proteins, to be probed at extremely shallow depth, typically less than 100 microns. This allows ESM to create an optical slice, with dimensions comparable to a thin electron microscopy section.

The new study describes the use of ESM to detect four model proteins: bovine serum albumin (BSA), mouse immunoglobulin G (IgG), human immunoglobulin A (IgA) and human immunoglobulin M (IgM).

Protein-protein interactions, including the rapid binding and dissociation of individual proteins, were observed in a series of experiments. Understanding such binding kinetics is essential for the design of safer and more effective drugs. The researchers also used ESM to keenly observe conformational changes in DNA, further demonstrating the power and versatility of the new method.

More Science and technology

ASU and Deca Technologies selected to lead $100M SHIELD USA project to strengthen U.S. semiconductor packaging capabilities

The National Institute of Standards and Technology — part of the U.S. Department of Commerce — announced today that it plans to…

From food crops to cancer clinics: Lessons in extermination resistance

Just as crop-devouring insects evolve to resist pesticides, cancer cells can increase their lethality by developing resistance to…

ASU professor wins NIH Director’s New Innovator Award for research linking gene function to brain structure

Life experiences alter us in many ways, including how we act and our mental and physical health. What we go through can even…