Shundene Key isn’t sure when she decided she wanted to become a scientist. Or why.

“I don’t recall,” Key said. “But even when I was young, I was always curious about learning new things.”

Sometimes, a child’s interests are replaced by an adult’s practicality. The 8-year-old who dreams of being a fireman becomes an engineer upon adulthood.

But Key, a second-year PhD student in Arizona State University’s School of Molecular Sciences, never lost her curiosity or love for science, and it’s led her here:

Key was recently awarded a National Science Foundation Graduate Research Fellowship Program grant funding her work on surface proteins in the immune system. As a recipient, Key received a five-year fellowship that includes three years of financial support, including an annual stipend of $34,000 and a cost of education allowance of $12,000 to ASU.

“I am honored and humbled for receiving this prestigious award,” Key said. “I feel it’s a recognition of all the hard work I have put in over the years. Having this opportunity means I can devote my time toward my research and training as a scientist.”

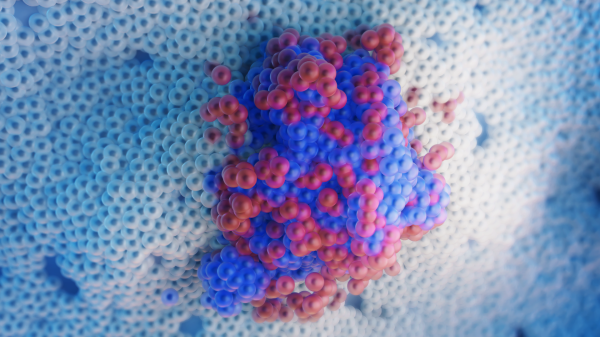

That research centers on surface proteins in the cells of the immune system that sense bacteria and viruses. When turned on, the proteins stick to pathogens so they can be cleared by the system. But if the proteins are turned on too early, an inflammatory disease like Crohn’s or psoriasis can occur. Conversely, if they don’t turn on when necessary, the immune system can’t fight off pathogens.

The goal of Key’s project is to understand how the proteins are turned on and what external stimuli can turn them on. If successful, doctors could control the activities of the proteins to either treat inflammatory diseases or devise ways to fight cancer with the immune system.

“We only want these cells to attack bad bacterial viruses,” said Key’s adviser, Xu Wang, an associate professor in the School of Molecular Sciences. “We don’t want them to attack us. So we really want to regulate when these sticky proteins are active and when they’re not.”

That’s the science. But there’s more to Key’s story. In fact, her journey exemplifies a line in ASU’s charter: "ASU is a comprehensive public research university, measured not by whom we exclude but rather by whom we include and how they succeed."

Remember those last three words: How they succeed.

Key transferred to ASU in the fall of 2014 after getting her associate degree at Haskell Indian Nations University in Kansas. A member of the Navajo Nation who grew up in Mesa, Arizona, Key chose ASU in part because it had a biochemistry degree, but also because of its resources for Native American students, such as the American Indian Student Support Services (AISSS) and the American Indian Graduate Student Association.

“I got to connect with other Indigenous students who had the same goals as I did, as far as education goes,” Key said.

Key got to know Laura Gonzales-Macias, now the interim director of AISSS. When, in 2017, Key expressed her desire to work in a laboratory, Gonzales-Macias connected her with Otakuye Conroy-Ben, an assistant professor in the School of Sustainable Engineering and the Built Environment in the Ira A. Fulton Schools of Engineering.

Gonzales-Macias understood that beyond the professional help Conroy-Ben could give Key, she could also be a personal mentor. Conroy-Ben is a member of the Ogala-Lakota tribe from the Pine Ridge Indian reservation in South Dakota.

She was the first Native American female scientist Key had met.

“Having an Indigenous mentor with a common background really helped,” Key said. “She knew of resources that could help me in the areas I was interested in.”

Their conversations weren’t always about science. Conroy-Ben and Key talked about the cultural barriers that limit educational opportunities for Native American women.

“There’s a lot of responsibility on us to take care of our families,” Conroy-Ben said. “To not be so self-serving but to think more of the community.”

Key was fortunate. Her mother encouraged her to get an education so she would have more “opportunities in life.” Still, Key said, ASU’s commitment to both a diversified student population and faculty was critical for her. And in Conroy-Ben, she met a woman who shared her background, who understood where she was coming from and what she was looking for.

“I am lucky to have met women of color in powerful positions, whenever I need advice or encouragement,” Key said.

Perhaps Key would have reached this point, becoming an NSF grant winner, had she not been mentored by Conroy-Ben. She’s a smart young woman who, colleagues say, wants to dive into the work and further her ambitions.

“I’ve often provided letters of recommendation for her, and she’s made it really easy because she’s so amazing,” Gonzales-Macias said.

But consider this: According to the National Science Foundation, only 0.1% of scientists and engineers are Native American women. Key found that 0.1% at ASU.

“To have that type of mentorship and bring somebody under your wing is very powerful,” Gonzales-Macias said. “There’s a relatability, a sense of belonging. There’s also that sense of, ‘You paved the way for people like me.’”

More Science and technology

From food crops to cancer clinics: Lessons in extermination resistance

Just as crop-devouring insects evolve to resist pesticides, cancer cells can increase their lethality by developing resistance to treatment. In fact, most deaths from cancer are caused by the…

ASU professor wins NIH Director’s New Innovator Award for research linking gene function to brain structure

Life experiences alter us in many ways, including how we act and our mental and physical health. What we go through can even change how our genes work, how the instructions coded into our DNA are…

ASU postdoctoral researcher leads initiative to support graduate student mental health

Olivia Davis had firsthand experience with anxiety and OCD before she entered grad school. Then, during the pandemic and as a result of the growing pressures of the graduate school environment, she…