Before a piano produces beautiful music on stage, the care and maintenance of its 12,000 parts is itself a complicated and delicate symphony.

At Arizona State University, Rick Florence has spent almost 30 years carefully coaxing the most perfect notes possible from the pianos as the head piano technician in the School of Music, Dance and Theatre.

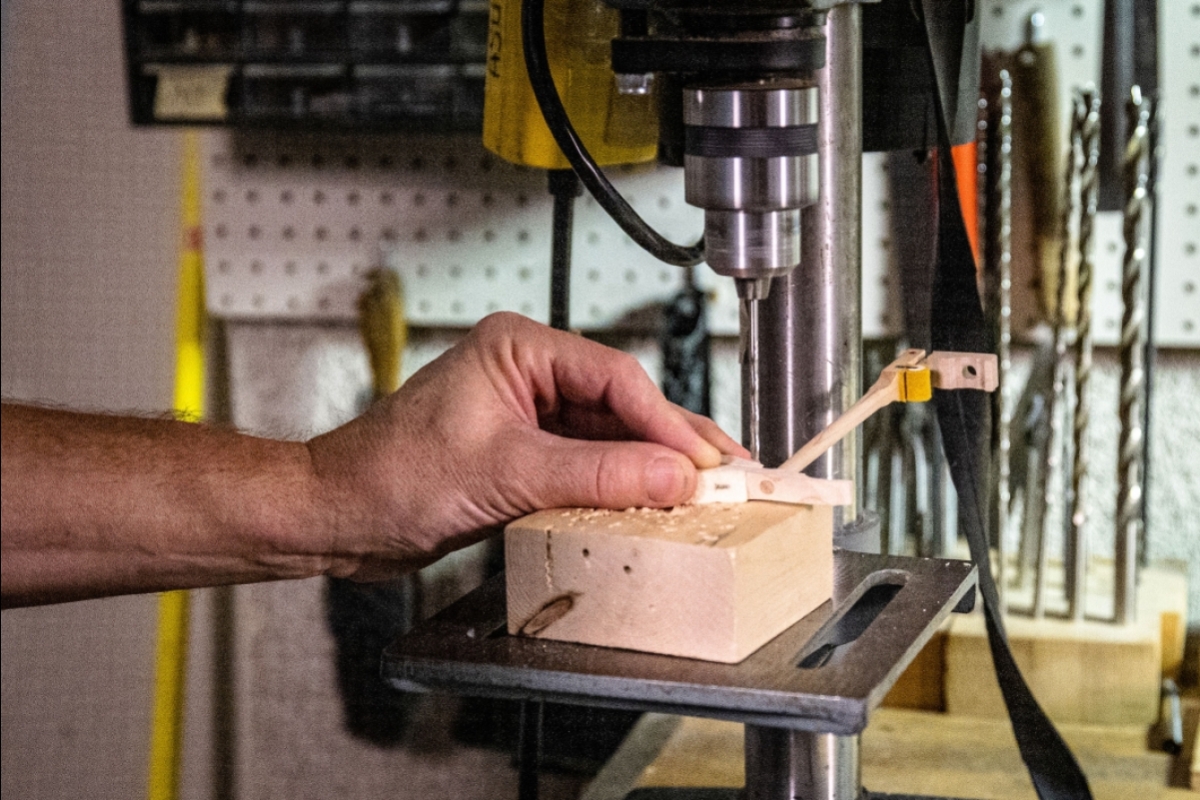

Based out of his workshop in the basement of the Music Building, he — along with a part-time colleague, Keith Cannon, and student workers — maintains a schedule for all the pianos, which can range from simple tuning to completely rebuilding the interior every few years.

Over the years, Florence has developed a complex system to balance and “regulate” the instruments. He can remove the “action” of the piano – the keys, the hammers that hit the strings and the thousands of parts in between — like a big drawer and take it to his workshop.

Recently, Florence replaced the hammers and balanced the action of the John Lennon Imagine grand piano that was donated to ASU. That piano is being used in the recording studio of the Popular Music program at Fusion on First in downtown Phoenix.

John Lennon's self portrait adorns the music desk of the John Lennon Imagine Series Limited Edition Steinway concert grand piano in its new home at a Fusion on First studio. Photo by Charlie Leight/ASU News

“We try to make each piano as consistent and predicable as possible for the pianist,” said Florence, whose title is manager of keyboard technology and event services.

“A good pianist will always be able to adjust their playing, but they’ve studied and practiced for that recital, and they deserve a piano that’s in pristine shape.”

In honor of National Piano Day on March 29, the 88th day of the year because a piano has 88 keys, Florence answered some questions from ASU News.

Question: How did you become a piano technician?

Answer: I’m a third-generation piano technician on my mom’s side. Every month, the family would get together for a big meal and there was discussion ad nauseum about the pianos and I thought I would never do this. Never.

Then I went to college and decided to apprentice in my grandfather’s shop for a year to tune pianos to pay for college. I changed my major a few times and I was hating school. My tuning business was growing, my family was growing and I was enjoying it. I worked privately for 10 to 12 years when the job at ASU opened up.

When I arrived at ASU in 1992, I had a solid foundation of training and experience, mostly due to my work with Yamaha Corporation and training in my grandfather’s shop. I had no idea how little I knew. Working at a university, especially at ASU, is like working in a live-in laboratory. (The use of a piano for) one academic year is equivalent to closer to 10 years in a typical home.

The upside to this accelerated use is the ability to see, firsthand, how materials and procedures hold up, and make necessary adjustments. This has enabled us to develop action building and voicing and regulating procedures that have improved our ability to support the music program.

Rick Florence, manager of keyboard technology and event services for the School of Music, Dance and Theatre, weighs the keys of the recently donated John Lennon Imagine Steinway grand piano in his workshop in the Music Building. He rebuilt all the hammers of the piano. Photo by Charlie Leight/ASU News

Q: A donor recently gave ASU an exquisite John Lennon Imagine Steinway grand piano. How many pianos does the School of Music, Dance and Theater have?

A: There are about 185 pianos in the School of Music, Dance and Theatre. This varies year to year. The value of the pianos is just under $8 million if we were to replace them.

Piano donations are not uncommon. Someone donated a 1916 Steinway Model O that is now being restored to be used at Mirabella, which raised the funds to restore it. And we had an 1898 Steinway model A donated to Kerr Cultural Center, which was also restored.

Q: What is the difference between regulating a piano and tuning it?

A: When you have a piano tuned, you’re changing the tension of the strings. It doesn’t affect the other parts. Too often, pianos are just tuned. It’s like only putting gas in your car and doing no other maintenance.

We don’t just tune pianos, we’re always adjusting the voicing and regulation. On a regular basis, we pull actions down to the shop, changing parts if needed and making adjustments. At some point, we replace all the hammers and other parts.

Our performance pianos in Katzin Concert Hall are checked every day, and sometimes multiple times a day if there are many recitals.

Q: How do you regulate a piano?

A: Regulation is the adjustment of the mechanism of the piano – the action. There are 28 separate adjustments for each note – adjustments such as parts alignment, spring strength and key travel. Regulation is optimized when an action is first balanced. To balance the action, we use a system designed by David Stanwood, a piano technician in Boston. What the system does is removes friction from the equation while you’re taking measurements, and it pays more attention to inertia, which is huge in the way a piano feels from key to key.

An action is a collection of levers. They all work together to create one ratio, meaning for every millimeter the key goes down, how many millimeters does the hammer go up? It’s generally a 5 to 1 ratio, but it varies dramatically from piano to piano, and sometimes from note to note.

Think of 88 different seesaws of different lengths and weights.

We have incorporated this program into a spreadsheet, with the help of a brilliant past student worker, Robert Springer, and we take measurements of each piano part and it tells us the actual ratio. We can then change out parts, if needed, to optimize the ratio of the action. Then we go through and adjust the strike weight — the weight of the hammer and shank that hit the string — and then, based on the calculation of the program, we adjust the key weight.

Once we’ve done that, it’s done. We keep these records because the keys don’t change, but we replace the hammers quite often. We can reproduce that same feel of the action by reproducing the strike weight.

Video by Ken Fagan/ASU News

Q: Do you teach?

A: I teach a course for pianists, who typically are not informed about the technology of their instrument.

They show up and they’re expected to play a piano that’s not theirs. The violinist takes their violin, the flutist takes their flute. The pianists are at the mercy of the piano itself, the venue, the skill of the technician and things that are totally out of their control, but yet they’re being judged on how well they’ll play.

So I teach “Introduction to Piano Technology.” The idea is to understand how a piano works and how to communicate better with a technician.

I also have an internship class, and the students can work here in the shop for credit.

Q: Does the musical genre matter when you’re working on a piano?

A: Sometimes we voice slightly differently. For example, a jazz pianist wants a little more attack. And a classical pianist usually wants more color, so you can go from velvety soft to growly. Voicing includes manipulating the shape and flexibility of the hammers, which allows for the color changes that pianists desire.

Q: What’s changed in your job since you arrived at ASU almost 30 years ago?

A: In 1992, we supported about 350 events per year, and we now are over 500.

Over the last 30 years, there have been incredible developments in parts availability, both in terms of quality and improvements to geometry. We have been able to act as a beta tester for a number of parts companies as they have improved their materials and production methods.

Q: In 1990, the importing of ivory was banned in the U.S. Does the school still have any pianos with ivory keys?

A: Up until three years ago, our main concert piano still had ivory. It was from 1986 and it was one of the last ones with ivory keys, but the ivory got so worn out that we finally had to replace them with plastic. It was sad to do because ivory has a nice feel to it.

I have a set of ivory keytops that I bought pre-ban, from a manufacturer that was going out of business. But when the ivory ban came down, we couldn’t use it. It would be illegal for me to put it on a key.

Q: Why is this work important?

A: We would pay $70,000 to $150,000 for a new institutional quality piano. We can rebuild one for about 35% of that. And we can make it how we want it.

Our whole job is about sustainability. How can we prolong these instruments and not have to chop down old-growth spruce and maple trees to make new pianos?

It’s about preserving natural resources and our budget, one piano at a time.

Top photo: Rick Florence, manager of keyboard technology and event services for the School of Music, Dance and Theatre, works on the keys and hammers of the recently donated John Lennon Imagine Steinway grand piano in his workshop in the Music Building. Photo by Charlie Leight/ASU News

More Arts, humanities and education

‘It all started at ASU’: Football player, theater alum makes the big screen

For filmmaker Ben Fritz, everything is about connection, relationships and overcoming expectations. “It’s about seeing people beyond how they see themselves,” he said. “When you create a space…

Lost languages mean lost cultures

By Alyssa Arns and Kristen LaRue-SandlerWhat if your language disappeared?Over the span of human existence, civilizations have come and gone. For many, the absence of written records means we know…

ASU graduate education programs are again ranked among best

Arizona State University’s Mary Lou Fulton College for Teaching and Learning Innovation continues to be one of the best graduate colleges of education in the United States, according to the…