The desert is a place that tells stories. Petroglyphs. Tire tracks. Paw prints. The dried parchment of a shed snake skin.

Who was here. What they did. Where they went.

And so it is with the newest addition to Arizona State University’s Tempe campus.

The Interdisciplinary Science and Technology Building 7 is a building of the desert, not a building in the desert.

Although it won’t be christened until April, it was born with many tales to tell.

The idea, as envisioned by university President Michael Crow, was to create a living room for the university, a place that is a nexus for all the institution’s research.

“Every single move that was made was made in support of this mission to create a very holistic, comfortable, sustainable project,” architect Rachel Green Rasmussen said.

The $192 million building features 70,000 square feet of lab space. There is a 26% reduction in global warming potential, water-based climate control to reduce energy use, and the capacity to capture 100% of rain falling on it and direct it to landscape and aquifer recharge.

“A highly complex building,” project manager Carlos Diaz of McCarthy Building Companies called it.

The interior is full of surprises. There’s a break room in a stairwell, which sounds miserable, but it’s a lovely, unusual space.

“It’s a good-feel building,” Diaz added. “People feel good in here.”

The site: The history and the importance of water in the desert

An irrigation canal — long a part of this area of land — cuts through the courtyard of the new ISTB7 building. A number of historical elements were incorporated into the building's design. Photo by Deanna Dent/ASU News

The site has always been a crossroads. Today, it’s one of the busiest intersections in the state.

A thousand years ago, the site was used to process food, an archaeological study revealed. The Akimel O’Odham and the Piipaash people brought foods like mesquite pods here. There was a foot path and, later, a stage coach route. The first transcontinental highway — from Savannah, Georgia, to San Diego — ran through here. (A remnant has been preserved.) Waters from the Kirkland-McKinney ditchWhat remains of the Kirkland-McKinney are a few small segments of open ditch along Eighth Street and University Drive in Tempe. It is sometimes also referred to as the Hayden Ditch. powered the Hayden Flour Mill.

The Kirkland-McKinney was among the earliest irrigation undertakings in the Tempe area, named for William H. Kirkland and James B. McKinney. With help from the area’s Hispanic residents, it is estimated the Kirkland-McKinney branch was constructed between 1869 and 1870, which makes it the oldest extant and in-use water conveyance in the SRP system.

The Hayden branch was developed roughly a year later as a part of Charles Trumbull Hayden’s vision of creating a water-powered flour mill. This branch continued to serve Tempe until urbanization reduced the size of the branch and most of it was ultimately piped underground.

Water from this ditch system also helped support a thriving Spanish-speaking community made up of prominent families, such as the Sotelo family. The area was named after the family, known as the Sotelo Addition, and supported agriculture until the area began to urbanize around the midcentury mark.

It’s important to note that this canal and many others have deeper routes, and some date back before Europeans settled the Valley, built by the ancestors of the modern Akimel O’odham, who today are part of the Gila River and Salt River Pima-Maricopa Indian communities.

The ISTB7 incorporation of the ditch into the design of the building is unique, and SRP is in the process of working with ASU, the Bureau of Reclamation and Native American tribes to develop interpretive signage that tells the story of these canals.

Another bit of history on the land is a railroad spur line that linked Tempe to the greater Union Pacific rail network and the rest of the Southwest. Aspects from each of these historic elements have been preserved as part of the new structure.

“We wanted to be able to preserve and tell that story,” said Tom Reilly, architect with Architekton, one of the two firms who designed the building. “So less than 50% of the building touches the ground. … That creates that process.”

The site: The challenges

ISTB7, shown on Feb. 3, sits at one of the busiest intersections in the state. Photo by Denna Dent/ASU News

There’s a 28-foot grade from the intersection of University Drive and Rural Road to the top of the site. Both a working Salt River Project ditch and the light rail run through the site. And, as mentioned, it sits at one of the busiest intersections in the state.

It may well have been the most complex place to build something in Arizona.

“All of these things just to break ground,” said Diaz.

“I’m the oldest guy on the team, and I can tell you that it was the most challenging site that I’ve ever worked on. But the other side of that is there were hidden gems that I’ve never seen on another site, either," architect Tom Reilly said. “There were several times during the process when it looked like we were not going to be able to complete the building on that site. And inevitably, people rallied together and everybody wanted to do the right thing. They figured out how to do it.

"So it was a huge team effort from ASU, all the builders, all the designers, SRP, the Bureau of Land Management, the city of Tempe. It really was everybody kind of pulling together and getting excited about the vision and making sure that it happened despite the hurdles.”

Prepping

Architects on the project were Tempe-based Architekton and New York-based Grimshaw Architects.

First up was educating the East Coast contingent on all things Arizona.

“We threw the New Yorkers into all the aspects of the desert,” said Rasmussen, an architect at Architekton. “We did rides along the canals. We went and hiked in the desert. A lot of things to really get them to understand the plant materials and the kind of beauty that I think we’ve all come to recognize that really seeps into your soul here about desert living.”

Eric Johnson, an associate at Grimshaw, said “With Architekton, you guys taught us a lot about shading and kind of the appropriateness of materiality in Arizona.”

A geode

The "slot canyon" on the east side of the building hints at ISTB7's geode inspiration — a hard exterior with a sparkling interior. Photo by Charlie Leight/ASU News

The concept behind the building is a geode. The exterior is hard and crusty, but in the interior courtyard, there’s an abundance of light and sparkling glass.

“When you crack the geode open, there’s all this excitement, there’s all this kind of reflection happening inside the geode,” Johnson said.

The interior is also seen as a riparian area, with water flowing through and cool blue walls inspired by the Havasu Falls in the Grand Canyon.

“You can get glimpses into that idea as you kind of walk around the building,” Johnson said. “There’s the slot canyon to the east where you can see into this blue, green material with all its reflections that we provided.”

The skin

The building is clad in a shell of glass-fiber-reinforced concrete panels. It absorbs and stores less heat.

It’s on track for LEED V4 Platinum certification; “significantly harder from a building performance standpoint,” Diaz said. The air conditioning systems only bring in fresh air as needed.

“How do you create a skin that actually does not hold that heat? That slows down the heat transfer into the building?” university architect Ed Soltero said. “We’ve delayed that, so that the mechanical systems have been downsized completely and we don’t expend a lot of energy.”

The panels are based on biomimicry of a saguaro’s orientation to the sun. The commanding cactuses shield themselves from the heat with the deep pleats of their skins. South-, east- and west-facing windows are heavily shaded by the angled concrete panels, while the north-facing windows are barely covered.

“As you walk around the building, you’ll find that some of the panels are much more open than others on the south facade,” Johnson said. “It’s very much closed in to cut down as much of the solar gain on the facades as possible, but we’ve also lifted the skin a little bit to provide almost like a hood or, or a visor, so that you're blocked from the sun in one direction, but you’re seeing out in another direction obliquely. ... The real move here is definitely to provide a skin that’s responsive to the solar angle.”

Shade

The north of the building is very open, and the south is very closed. In winter, the courtyard will be fully illuminated, but in summer it’s fully protected. Ancestral Puebloans oriented cliff dwellings in the same way. The bridge over University Drive also has a shading element.

“We were inspired by Native American dwellings in the Southwest that have a similar massing of the building, where we lifted the mass of the building to allow sun to kind of reflect underneath the building in the winter months and get as much of a comfortable atmosphere under the building in the winter, but in the summer, the entire building shields the courtyard and what’s underneath the building from that harsh summer sun,” Johnson said.

There’s a nexus between history, shade and the building’s height. Lifting the building to protect the irrigation ditch is a statement.

Johnson described it: “Look, this is something that we respect, and that has been here in our history. We’re not just going to cover it up with a building and put a plaque up and say there once was a canal and it stood here. We’re actually engaging with that canal and using it to irrigate our plants and to cool the micro climate under the building. So people will sit next to the canal and feel a little bit of shelter from the sun, but also the cooling nature of the water will help to kind of create these micro climates as well.”

Photo by Charlie Leight/ASU News

Airflow

Ancient buildings in the Middle East had what university architect Soltero calls a shadow network. There’s a progressive sense of arrival when you arrive at a garden, in shaded courtyards, in a shaded alleyway. And those shadow networks create air movement.

There’s a simple idea in thermodynamics: Hot goes to cold. If you can shade a place (in an area that’s not windy), the hot air will try to go to the cool shaded area.

When the architects did the computational flow dynamics for ISTB7, they did a heavy-duty engineering analysis and induced an airflow. You might not feel it, but it’s there.

The story

The building tells its stories both horizontally and vertically.

As you walk in from the Rural Road intersection, you pass a display space for stone tool-making, part of the Institute of Human Origins. Passersby will be able to watch grad students chip away at hunks of obsidian. Walk across the atrium, over the canal and past the light rail tracks, and a mechanical tree that captures carbon from the environment awaits. You have just traversed the length of human experience.

“So that’s where it starts to talk about, OK, we can learn from history and learn from our past, and then how do we re-create it and talk about our modern technologies and where we’re going in the future in order to continue to survive and thrive on this planet?” Rasmussen said.

As you climb the building, you will pass the Institute of Human Origins on the second floor, with a cast of the Lucy skeleton on display — one of the oldest known human ancestors, discovered in 1974 by ASU paleoanthropologist Donald Johanson. The third floor houses sustainability initiatives and its school, along with the Global Locust Initiative and Urban Resilience to Extremes Sustainability Research Network. On the fourth floor are located the College of Global Futures leadership and administration, the Swette Center for Sustainable Food Systems, the Humanities Lab and related units. The fifth floor is home to the Julie Ann Wrigley Global Futures Laboratory leadership and administration, the Global Institute of Sustainability and Innovation, LightWorks, the Center for Global Discovery and Conservation Science and the newly established ASU-Starbucks Center for the Future of People and the Planet, among other groups.

Junior anthropology major Isabella Boker works on cutting foam for the storage of skull artifacts at the recently completed Institute of Human Origins space in ISTB7 on March 8, 2022. Photo by Deanna Dent/ASU News

“The building is really talking about our kind of deep past all the way to our global future,” Rasmussen said. “And so it was a very strong commitment from the university and the design team from all aspects to really make that sing.”

In one of the first meetings the architects had with all the groups using the building, the concept was unveiled.

“Honestly, it’s like the room started vibrating and they said, ‘Gosh, you guys are studying deep time and how we became human, and we’re studying future time and how we’re going to remain human on this planet and create a healthy planet for us to remain,’” Reilly said. "They saw it immediately. So it was very easy for us to latch upon that and talk about how things were stacked, how the sections worked to be able to tell that story within the building itself.”

One of the project’s original goals was to create a place where the public could see how ASU research is changing the world.

“A lot of this was about that porosity that we talked about,” Rasmussen said. “A lot of it was linking the light rail station to the new Novus development across University Drive, the building with the bridge, and then also the sports venues up there. So as people are coming to the campus for other things, they get drawn through this building, and the researchers will be putting on specific displays and research happening on any one of the ASU campuses will be using this. There’s a lot of nooks and places where we left space for those displays to happen.”

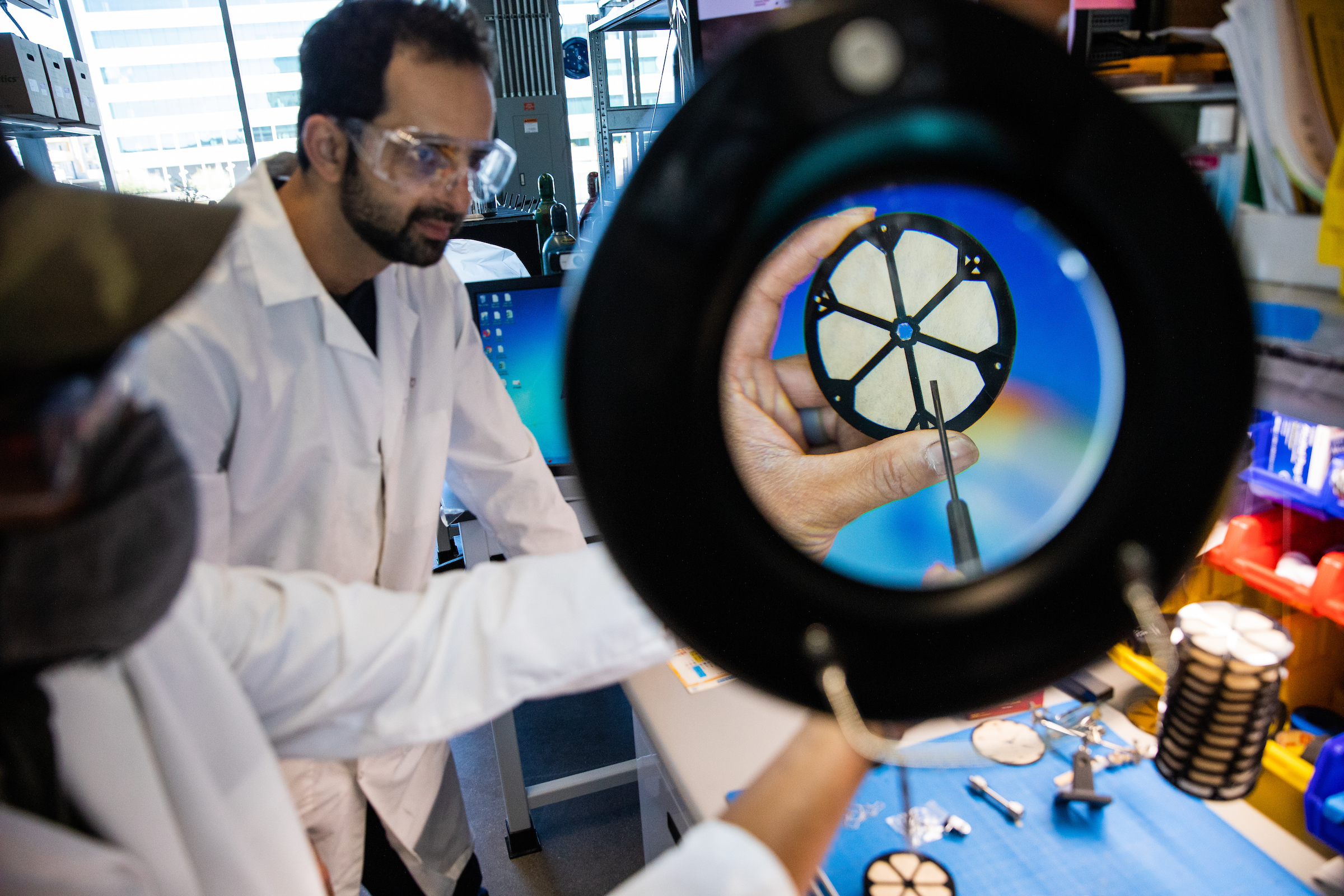

Mechanical engineer Jason Kmon (left) and doctoral student Thiago Barbosa examine a sorbent model in miniature being created for outreach purposes in the Center for Negative Carbon Emissions on March 7. Photo by Deanna Dent/ASU News

Creating a campus of the desert

The building is the latest addition to a campus with architecture that covers a range of styles. Soltero calls it an “architectural petting zoo.”

“This university doesn’t have a signature architecture per se,” he said. "Since I got here, I’ve been exploring this idea. How do we provide a signature for ASU? And the fact that we’re in a very stressed climate. I started looking to lessons of antiquity from all the places I’ve traveled in the world, in the Middle East and so forth. You follow the latitude light around the globe, you can get a lot of lessons from that in terms of the shade and shading. And so what I’ve been trying to do is create an architecture that creates a humane environment that creates a place of respite.”

Since Soltero began at ASU, he has been involved with buildings like Biodesign C, the Student Pavilion and the Beus Center for Law and Society.

(He is currently a doctoral candidate at ASU and an aspiring scholar in desert architecture. His dissertation topic focuses on developing a framework for “desert-adapted modernism.”)

“We have been at the forefront of this experimental architecture, and Biodesign C has similar things,” he said. “That one has a perforated skin. The ratio of perforations is totally different on each facade, according to the orientation of the building. It’s really understanding thermodynamics, and then how do you actually visualize that?”

Exterior of ISTB7. Photo by Charlie Leight/ASU News

All the buildings that Soltero has been involved with have particular characteristics.

“Those buildings will make no sense in Helsinki or anywhere else, right?” he said. “They speak of the environment. These buildings are the desert, and they behave correctly in the desert. ... And this is something that we created internally here and working very closely with Dr. Crow and the leadership about how do we actually create an architecture that is of ASU and is unique to ASU, you know? And I think we’re on our way there.”

If the building has a lesson to teach, what is it? What should students take away from it?

“The lesson that they've got to take with them is that you need to carefully look at what your environment is telling you there and what the dynamics of the micro climate are telling you there,” Soltero said. “So you can come with the architecture that is responsive, that can be quite exquisite and quite beautiful. Don’t mimic what you see; you have to look deeper at the things that are invisible.”

Photo by Charlie Leight/ASU News

Top photo by Deanna Dent/ASU News

More Environment and sustainability

From K–12 to corporate upskilling, ASU guides learners of all ages to design a sustainable future

Editor’s note: This story is part of a series exploring how ASU tackles complex problems to create a thriving future.When Kennedy Gourdine was a high school student in Maryland, she conducted…

Sustainability leadership in action

Editor's note: This story was originally featured in a special edition of ASU Thrive magazine.ASU alumni are making an impact. From city government to corporate leadership, they’re working in every…

Sustainable plant-based polymers could replace endocrine-disrupting plastics

We humans produce enormous volumes of plastic waste, and we recycle very little — just 14% of the 590 billion pounds discarded in one recent year, worldwide. To make matters worse, exposure to…