As the COVID-19 pandemic continues to linger and we approach World Wildlife Day on March 3, many scholars among the Homo sapein variety of animal have found themselves pondering more than usual the relationship between themselves and their non-human counterparts.

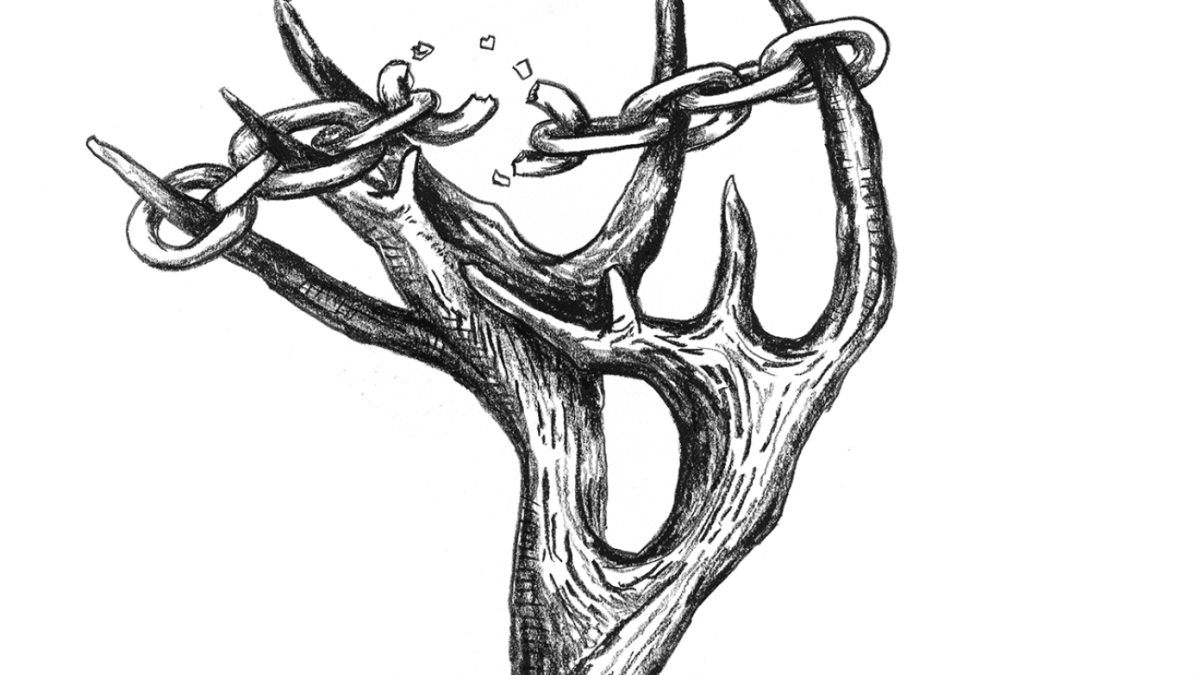

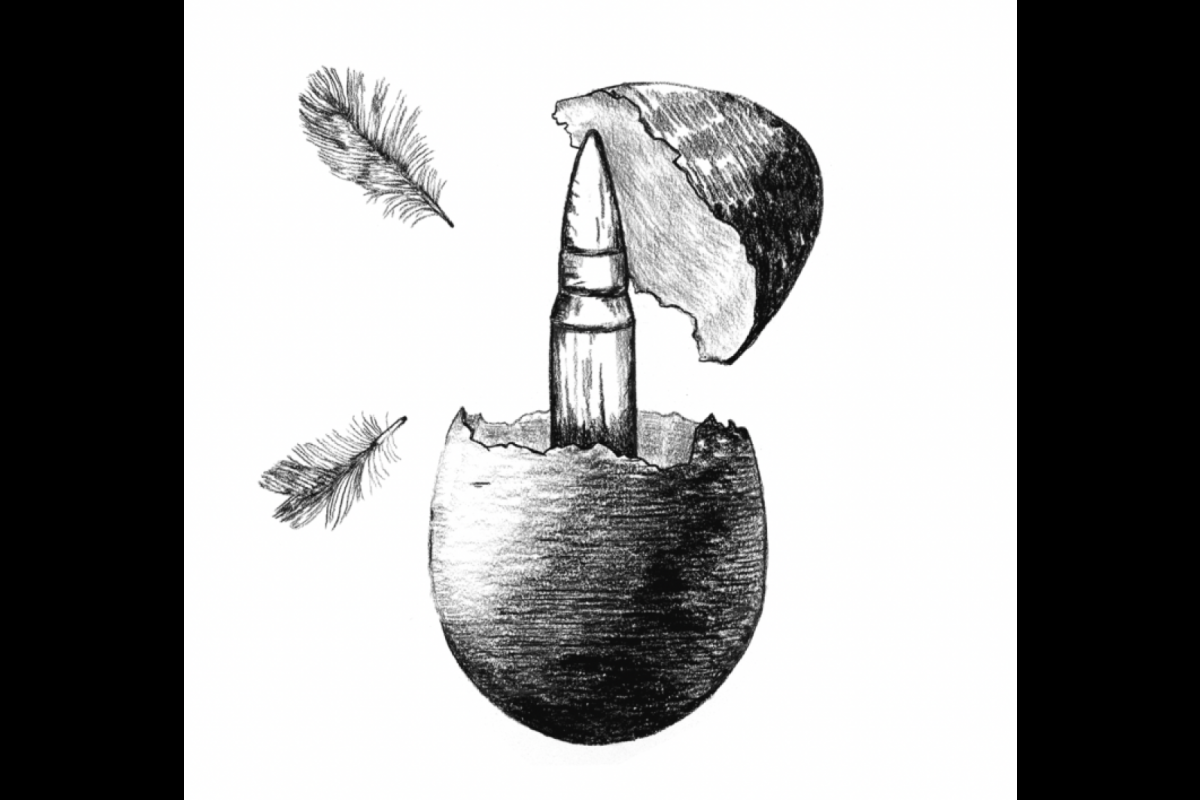

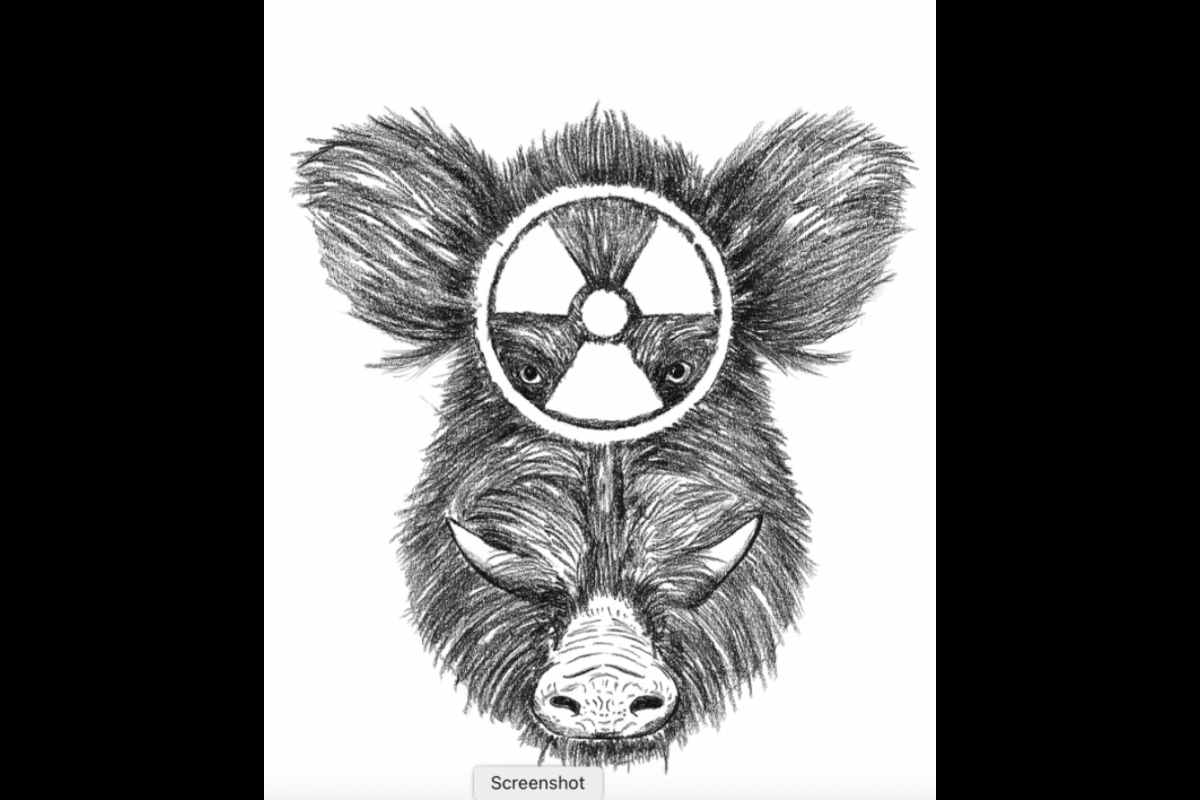

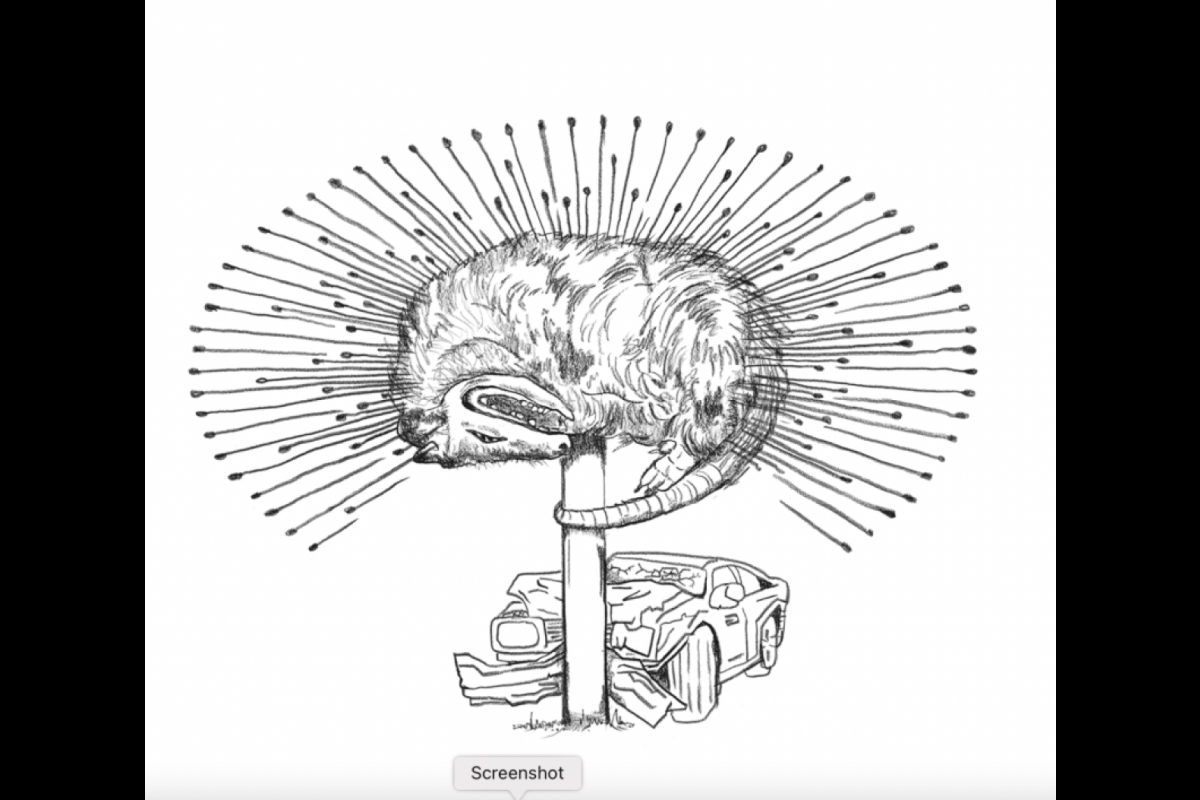

ASU English Professor Ron Broglio is one of them, and his new creative nonfiction book “Animal Revolution” takes a hard look at real-life incidents of animals crossing boundaries between their world and humans' – from reports of radioactive boar invading towns to jellyfish disarming battleships.

And it couldn't be more timely.

"If the coronavirus pandemic has taught us anything," the book jacket reads, "it is that we should pay attention to how we bump up against animal worlds and how animals will push back."

Broglio shared his intentions for the audience and his thoughts on the ways we can improve our complex relationship with the animal world.

ASU English Professor Ron Broglio

Question: Can you explain what nonhuman phenomenology is and how it relates to your book, "Animal Revolution"?

Answer: Phenomenology is how we carry ourselves in the world; another word is comportment, basically how we negotiate space. Every little detail is a constructed cultural element. It also has to do with our shapes, and our bodies, and how bodies move in the world.

Animals have that as well. They have differently shaped bodies, different sense organs, different ways of being in the world. Both in terms of being four-legged versus two, vertical versus horizontal, sense of smell versus sense of sight. Because we are sight-oriented, we skip over a lot of what is happening with the other senses.

It made me realize that animals live on the same Earth we do, but they’re in different worlds. Their sense perceptions are different. Their way of thinking about their surroundings is different. A lot of the book is about the tension between a shared Earth, but separate worlds.

Q: What do you hope readers will gain from this book?

A: Several things. The largest is that there’s a world outside of us. Humans and animals are on shared Earth. We live in different worlds and we are on shared Earth. We need to make room for them.

We are animals, too. If we listen to that part of us, to recognize the current culture is to distance ourselves from the Earth. If we instead listen to parts of us that really call to being engaged with the Earth as animals, then we become more sympathetic to the world around us.

Q: You collaborated with Marina Zurkow of the NYU Tisch School for the Arts to produce the illustrations for the book. How did she come to work on the book and how did her artistic style contribute to it?

A: She almost has a surrealist take on the stories, and takes them in another direction. And that’s what good art does; it doesn’t just come illustrative in a simple sense, but it creates a sense of wonder. I’m very interested in the power of non-verbal representation as pictures. I like the storybook style. I’ve known of Marina’s work for a very long time. She works on ecology, and she’s well-known for these kinds of surreal or magical takes on the world around us. Moving between the magical and the actual.

Are the animals actually in revolt? That’s sort of the poke at humans. It seems like it. It’s a reframing of actual events to make us think about larger questions. Her art also reframes the stories to point outside to a curious world around us.

Animals have done their job, my job is to report it in an interesting and provocative way, and Marina layers on top of that.

Q: In a perfect world, what does the relationship between humans, animals and our environment look like?

A: ASU has a Center for Biodiversity Outcomes ... Biodiversity means not just the major species have a space, but secondary and tertiary. All the different layers of species. The reason we need that abundance is that in hard times, a lot of things will be lost and a lot of species and animals will be lost, but the abundance is the fat that allows us to thrive in those times.

The idea is facilitating a world that accommodates more than humans. How are we accommodating bats? How are we accommodating bees? You can make spaces where these animals can thrive and dwell. In those cases, there’s no interference. In cases where there is interference, we can change our technologies to help.

Q: As a professor of animal studies, how have you seen ASU contributing to conservation efforts to support the local environment?

A: ASU, even on campus, is an interesting test lab because it’s an arboretum. We have some of the national leaders and national labs.

For example, bee studies. I just found out that Arizona has more bee species than anywhere in the Americas. I am actually leading a project now that is making pamphlets about different desert animals to get it out to college students and grade (school) kids and to the general public to become aware of animals around us and how cool they are.

Q: What are some changes we as humans can make in our everyday lives to form a better relationship with animals and our environment?

A: Notice all the animals around us, and then think of your own landscape or your own area and say, "How can I make this more hospitable?" By taking care of the local, which is the only thing you can kind of control in some ways, then that extends a certain sympathy to a global concern.

We often think about what we need, but birds need flyway spaces. Are we making flyway spaces? Butterflies who migrate here, they need milkweed. Is there milkweed around? There’s really basic elements of other worlds, and all the sudden, the world we live in becomes richer in texture.

Catch Broglio reading from his new book, “Animal Revolution,” at The Elizabeth Foundation for the Arts in New York City, Saturday, March 24. The event will be simulcast via Zoom starting at 6:30 p.m. ET.

Top photo: Illustration by Marina Zurkow for Ron Broglio's book "Animal Revolution."

More Science and technology

Turning up the light: Plants, semiconductors and fuel production

What can plants and semiconductors teach us about fuel production?ASU's Gary Moore hopes to find out.With the aim of learning how to create viable alternatives to fossil-based fuels, Moore — an…

ASU technical innovation enables more reliable and less expensive electricity

Growing demand for electricity is pushing the energy sector to innovate faster and deploy more resources to keep the lights on and costs low. Clean energy is being pursued with greater fervor,…

What do a spacecraft, a skeleton and an asteroid have in common? This ASU professor

NASA’s Lucy spacecraft will probe an asteroid as it flys by it on Sunday — one with a connection to the mission name.The asteroid is named Donaldjohanson, after Donald Johanson, who founded Arizona…