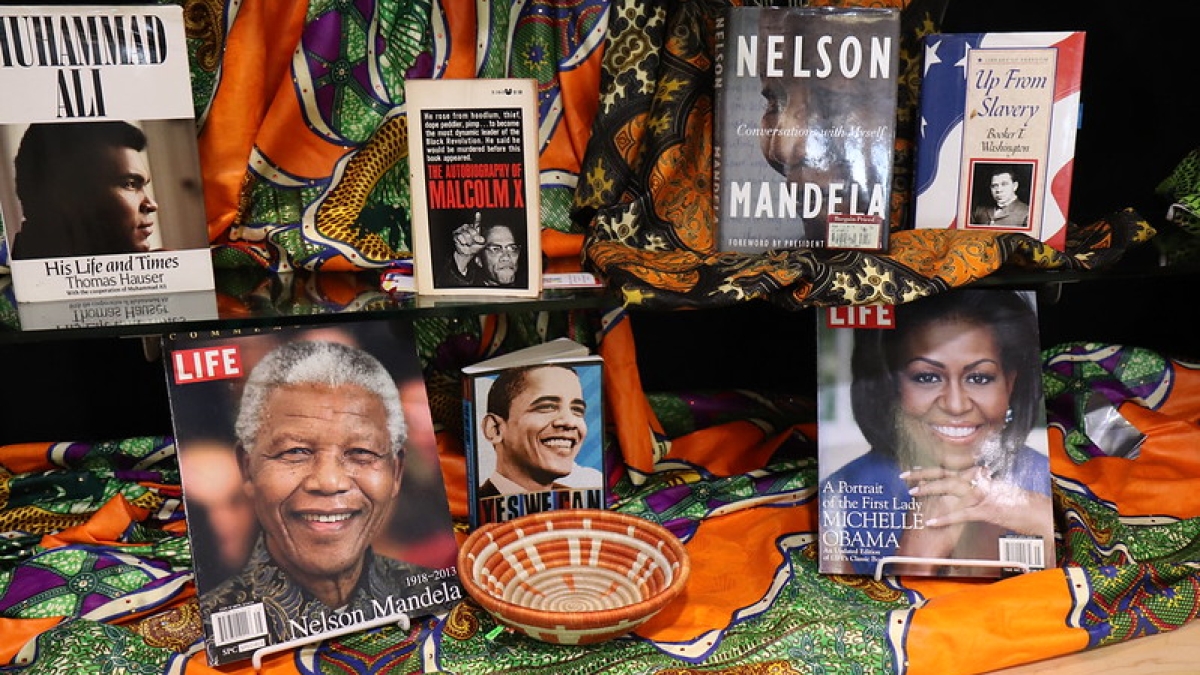

Martin Luther King Jr., Rosa Parks, Muhammad Ali and Maya Angelou are among the notables frequently mentioned in conversations related to Black History Month — and rightfully so.

But what do we know about other Black change-makers; the many who have gone uncited in history books — the female orators and journalists, the astrophysicists and meteorologists, the music therapists and composers?

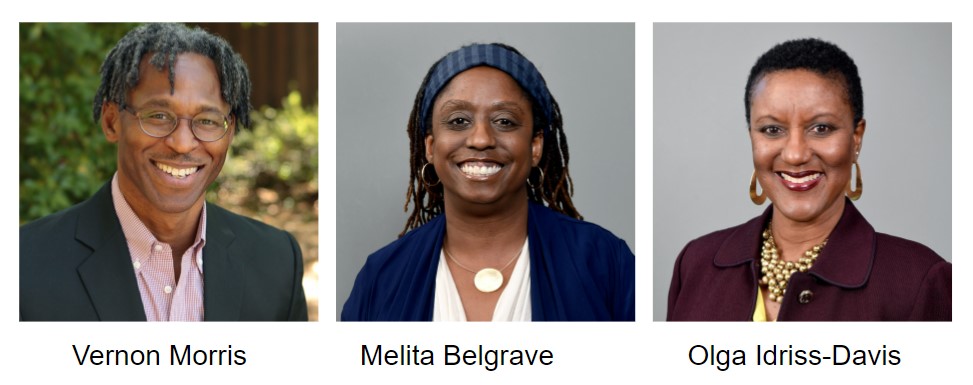

In honor of Black History Month, we asked three Arizona State University professors to discuss some of the unsung champions of their fields. Here, Vernon Morris, Melita Belgrave and Olga Davis talk about the men and women who continue to inspire their research and instruction.

June Bacon-Bercey: Forecasting the future of meteorology

An international expert on weather and aviation, June Bacon-Bercey was the first African American woman to earn a degree in meteorology in the United States, and the first female TV meteorologist trained in meteorology in the U.S.

Vernon Morris, director and professor in ASU’s School of Mathematics and Natural Sciences, says Bacon-Bercey is one of several pioneers in climate and environmental sciences that has inspired and informed his career as an atmospheric scientist.

June Bacon-Bercey

Bacon-Bercey worked for the National Oceanic and Atmospheric Administration (NOAA), an organization for which Morris himself later served as the principal investigator and founding director of the NOAA Cooperative Science Center in Atmospheric Sciences and Meteorology. She also worked for the National Weather Service and the Atomic Energy Commission, all at a time when men greatly outweighed women in scientific fields.

Morris says Bacon-Bercey was always thinking about helping the next generation of climate scientists, even using the money she won on a TV quiz show in 1977 to establish a scholarship for women. She also published an analysis of African American meteorologists in the U.S. with the intent to increase the participation of African American women in meteorology, and she used her platform to encourage women to be persistent and resilient in the field.

Bacon-Bercey co-founded the American Meteorological Society’s Board on Women and Minorities. In 2000, she was recognized by the National Science Foundation and NASA as a minority pioneer for her achievements in atmospheric sciences.

Born in Wichita, Kansas, in 1928, Bacon-Bercey died in 2019 in Burlingame, California. She was 90 years old.

George Carruthers: Widening the scope

George Carruthers, a physicist, engineer and space scientist, is another science innovator Morris says opened his mind and eyes to a career in science.

George Carruthers (center) principal investigator for the Lunar Surface Ultraviolet Camera. Photo courtesy NASA

In 1969, Carruthers invented and patented the image converter to detect electromagnetic radiations in short wavelengths. His innovative telescope was used during Apollo 16, the NASA mission that landed the first moon-based space telescope. Listen

Born in Cincinnati in 1939, Carruthers reportedly built his first telescope at the age of 10 using cardboard tubing and lenses he purchased through the mail with money he earned making deliveries. He earned his PhD in aeronautical and astronautical engineering at the University of Illinois at Urbana-Champaign in 1964 and began working at the U.S. Naval Research Laboratory (NRL) that same year.

Even though his research and innovation was highly regarded and frequently recognized, Morris says Carruthers shied away from the spotlight. Still, he was vigilant in helping the next generation of scientists and engineers achieve their goals, creating program pathways for high school students to work at the NRL and teaching courses in earth and space sciences at Howard University after he retired from the NRL.

Morris says he is also a direct beneficiary of Carruthers’ generosity and legacy, crediting Carruthers for helping him start up his own research lab early in his career.

Carruthers died in Washington, D.C., in 2020 at the age of 81.

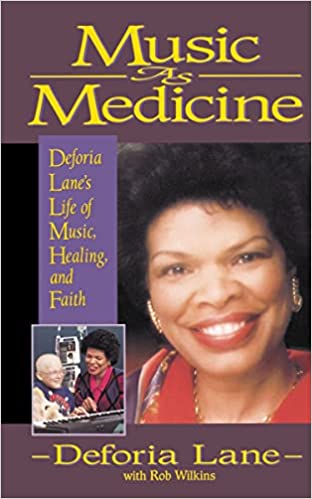

Deforia Lane: Science and sound healing

Melita Belgrave, associate dean and associate professor in the School of Music, Dance and Theatre, says Deforia Lane has been an inspiration and role model for her research and practice in the field of music therapy. Lane has been recognized for designing a number of music therapy programs for adults and children navigating a wide range of emotional, mental, physical and terminal challenges.

Her work has been so successful that she was the country's first music therapist to receive grant money to study music's therapeutic effects on cancer patients.

Belgrave says although Lane has managed to break through as a significant contributor to the science and practice of music therapy, there are a number of other Black women who have been largely overlooked or forgotten for their contributions to the field and whose works are also worthy of recognition.

Belgrave says representation matters on many levels and recalls how Lane inspired her as a young college student. She says it has been an honor and privilege to get to interact with Lane as a professional and peer in recent years.

Belgrave recommends Lane’s book “Music As Medicine: Deforia Lane’s Life of Music, Healing and Faith” for those interested in learning more about Lane’s life and career as a music therapist.

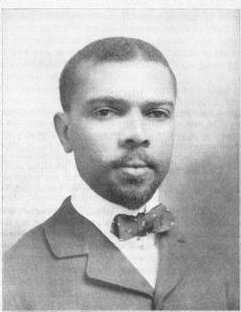

James Weldon Johnson: Poets and anthems

James Weldon Johnson

The ASU Choirs’ revival of the song “Lift Every Voice and Sing” inspired Belgrave to revisit the history of the song and its composer, James Weldon Johnson.

The song, widely regarded as the Black national anthem, was initially written by Johnson as a poem for educator Booker T. Washington for Washington’s visit to a school in Jacksonville, Florida, in 1900. Soon after, Johnson enlisted his brother, John Rosamond Johnson, to set the poem to music, and several years later the NAACP began to promote the hymn as the Black national anthem.

Belgrave says renewed interest in the song in recent years has given rise to new renditions, some of which include storytelling and conversation about why the song is important and what it means to people.

James Weldon Johnson died in 1938 at the age of 67.

Maria W. Stewart: Persuasive communication

The year was 1832. The place: Franklin Hall in Boston. The event: An historic address and call to action to resist slavery by one of the first women of any race to speak publicly to a mixed audience of men and women in the United States — Maria W. Stewart.

Olga Davis, associate dean of Barrett, The Honors College on the Downtown Phoenix campus and professor in the Hugh Downs School of Human Communication, says her exploration of Stewart’s rarely told impact began in graduate school when she wrote a dissertation on narratives by enslaved Black women and the liberating persona of these narratives. Davis said she was moved by Stewart’s courageous act of speaking up at a time when women were discouraged from speaking in public, sometimes with threats to their lives.

Over the next three years, Stewart made a total of four public addresses and published a political pamphlet and a collection of meditations before giving in to public pressure from those who wanted her to stop lecturing. Stewart later moved to New York City, where she taught in public schools, and then to Washington, D.C., where she continued to teach and write before her death in 1879.

Davis says Stewart’s essays and speeches presented ideas that became central to the struggles for freedom, human rights and women’s rights, and laid the groundwork for future generations of activists and political thought leaders. Listen

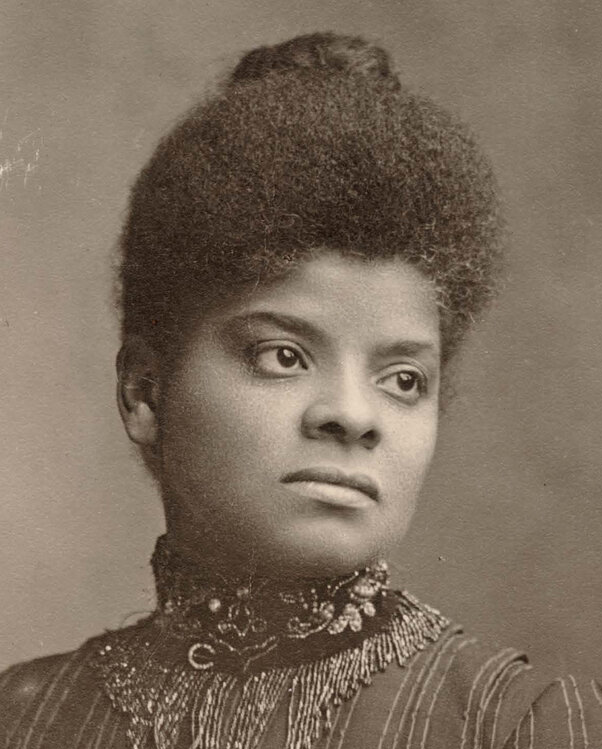

Ida B. Wells: Journalism and justice

Ida B. Wells

Social justice crusader Ida B. Wells is not an unknown figure in the annals of American history, but renewed attention and interest in the legacy of the investigative reporter and activist in recent years bears a refresher of why historians, according to The New York Times, considered Wells “the most famous Black woman in the U.S.” during her lifetime.

Davis says Wells was a fighter in many different realms — for racial justice, for women’s suffrage. Her persistence as a writer, speaker and organizer is well documented and continues to inspire to this day.

Wells became less of a household name in the decades after her death in 1931, but she has been back in the public eye in recent years as the subject of various news articles, editorials, exhibits and podcasts.

In 2018, the city of Chicago, where Wells lived and died, renamed a street for her, and in January 2022 toymaker Mattel released a limited-edition Barbie doll celebrating Wells as part of its “Inspiring Women” series. The doll is accessorized with a “Memphis Free Speech” newspaper — the newspaper Wells co-owned and wrote for, before a white mob invaded and destroyed the paper’s offices in 1892.

In 2020, Wells was honored posthumously with a Pulitzer Prize special citation for her work in journalism. Davis says the honor reinforces the impact of Wells, decades after her death. Listen

Top photo courtesy of Flickr.

More Law, journalism and politics

Can elections results be counted quickly yet reliably?

Election results that are released as quickly as the public demands but are reliable enough to earn wide acceptance may not always be possible.At least that's what a bipartisan panel of elections…

Spring break trip to Hawaiʻi provides insight into Indigenous law

A group of Arizona State University law students spent a week in Hawaiʻi for spring break. And while they did take in some of the sites, sounds and tastes of the tropical destination, the trip…

LA journalists and officials gather to connect and salute fire coverage

Recognition of Los Angeles-area media coverage of the region’s January wildfires was the primary message as hundreds gathered at ASU California Center Broadway for an annual convening of journalists…