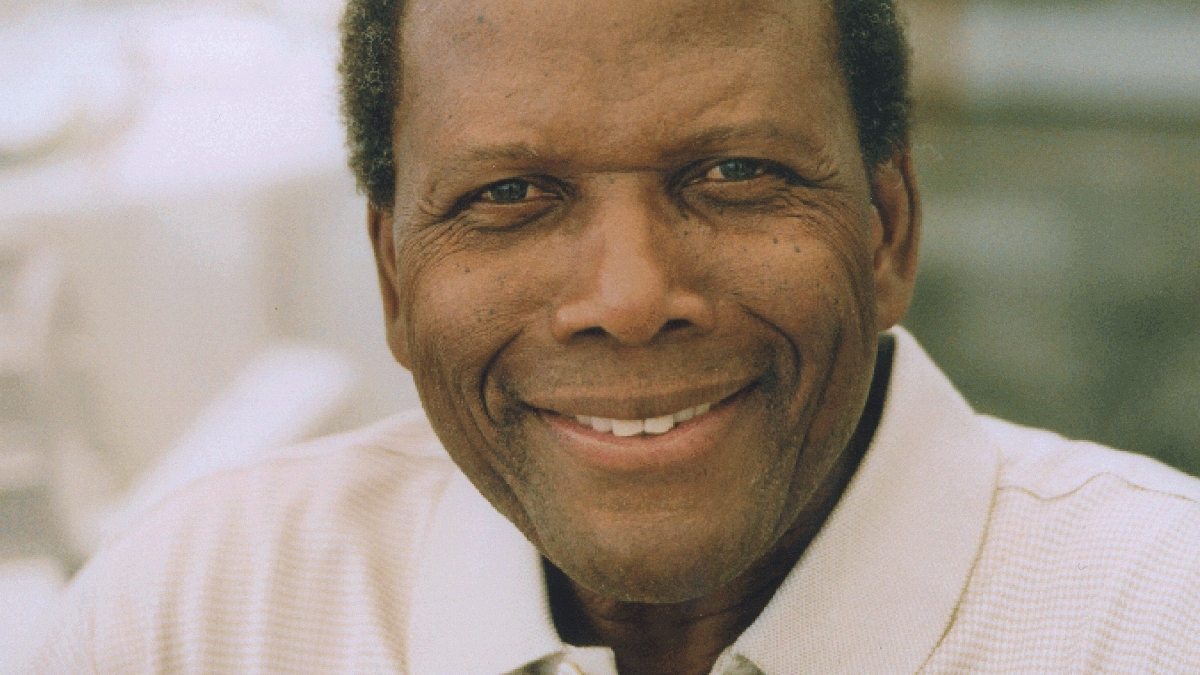

Sidney Poitier, a Hollywood icon who broke racial barriers in his roles and as the first Black man to win the best actor Oscar, left a legacy that will live on through film school students at Arizona State University.

Poitier, known for embodying characters with dignity and wisdom, died Thursday, Jan. 6, at the age of 94.

In 2021, ASU renamed its film school after the legendary actor and director in a move that signified the university’s commitment to inclusivity and diversity.

The Sidney Poitier New American Film School, with nearly 700 students, is one of five schools in the Herberger Institute for Design and the Arts at ASU.

The founding director of the film school, Cheryl Boone Isaacs, knew Poitier and called him “a beacon of light.”

“I first met Sidney Poitier decades ago because he was a friend of my brother’s, Ashley Boone, a pioneer in this business,” she said.

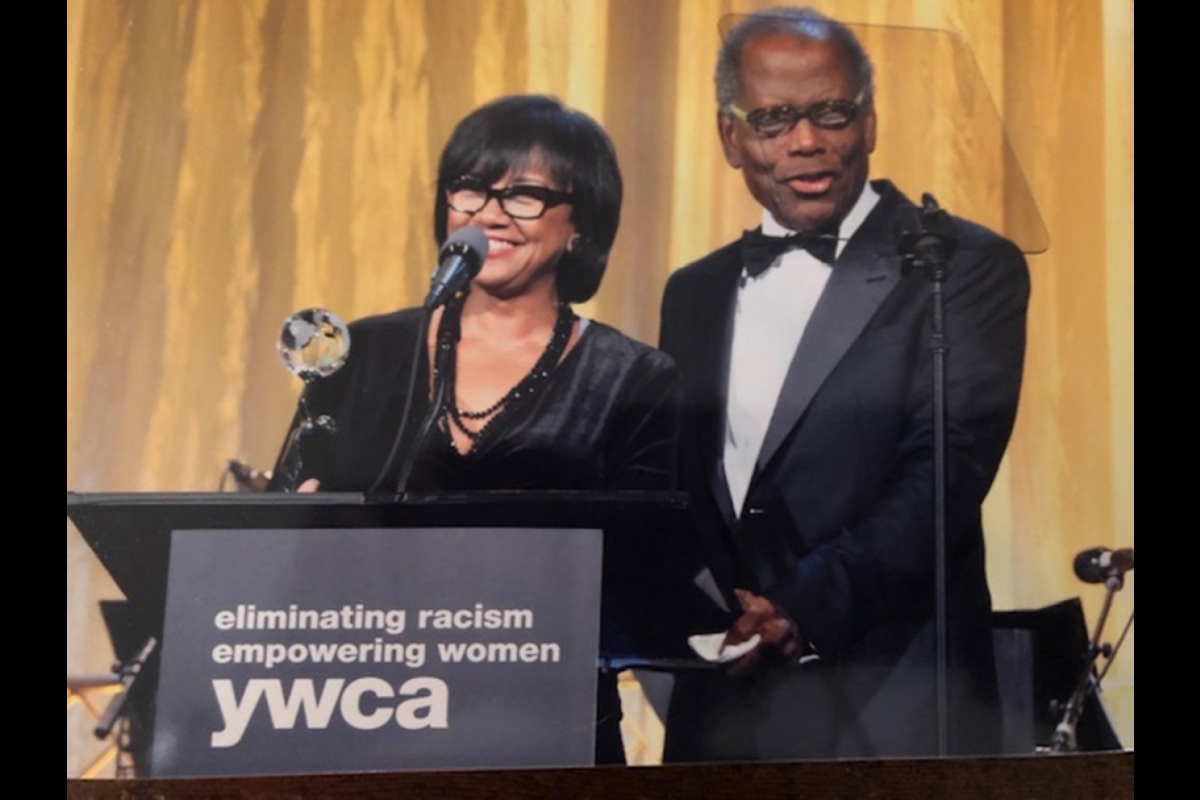

“Then when I got into the film business, I would run into him every once in a while, usually around Academy (of Motion Picture Arts and Sciences) events. And when I was elected president of the academy, our relationship solidified. When I was honored by Essence Magazine, Sidney presented me with the award, alongside Oprah Winfrey, and Sidney later presented me with an award I received from the YWCA of Greater Los Angeles.

“He always exemplified excellence, humanity — he was such a beacon of light that really lit the way for many of us, especially in the creative Black community.

“Sidney was far reaching in his philanthropic endeavors, his civil rights movement involvement. He always used his light to advance others.”

ASU President Michael Crow offered condolences to the Poitier family and everyone whose lives Poitier touched.

“It was with great sadness that we learned this morning of the passing of Sidney Poitier, an American film legend and an inspiration for countless people across the country and around the world, as well as the man for whom Arizona State University’s New American Film School is named,” Crow said.

“His contributions were immense and will be forever associated with grace, with talent and with striving to be your best while also being of service to others. He was self-made, he was committed to his craft, and our university and our students will hold his example at the forefront of what we do for generations to come.”

Poitier won the Oscar for his role in the 1963 film “Lilies of the Field,” which was shot and set in southern Arizona. He returned to Arizona twice more in the 1980s to direct “Stir Crazy” and “Hanky Panky.”

Attending a film school named for Poitier will connect ASU’s students to the continuum of history, according to Tiffany Ana López, the vice provost for inclusive excellence at ASU. She is the former director of the School of Film, Dance and Theatre in the Herberger Institute.

“He is an essential part of understanding American film history,” López said at the time of the renaming in 2021.

“He has a litany of ‘firsts,’ but it’s important for students and people following the film school to understand the impact of being first and to have people understand what is possible.

“This is why representation, seeing people who look like you on the screen, is so important. Because if you can’t see it, it’s hard to imagine being it.”

Many of Poitier’s movies addressed race, starting with “No Way Out,” a 1950 film in which he played a doctor who had to treat two white racists. In 1967 alone, he starred in three hit movies dealing with racial tensions: “To Sir, With Love,” “Guess Who's Coming to Dinner” and “In the Heat of the Night.”

In the fall 2021 semester, the film school offered its inaugural class on the life and legacy of Poitier, co-taught by López and Jason Scott, an associate professor and associate director of the film school. Students created final projects, such as proposals for films, videos and online content, as well as interactive installations, based on reading Poitier’s memoirs, watching his films and researching his impact on audiences and filmmakers.

López said that the students spoke about how studying Poitier’s work changed their viewpoints on film.

“His life and career helped them see the power of being yourself and having a strong work ethic, telling stories you want to tell and not what others expect from you, and, most importantly, making films about the people you care about,” she said on Friday.

The 2021 film school naming included a celebration video that featured remarks by three of Poitier’s six daughters.

Beverly Poitier-Henderson said at the naming: “It’s fitting that ASU is embracing his work ethic and embracing his commitment to truth and his commitment to the arts and his commitment to education. We’re very happy. He’s very happy.”

“It’s really important to have diversity in the stories that we tell, and they need to be told by the people who are living these stories and that’s a huge problem in this industry,” said Anika Poitier, who is a director and actor. “There are so many stories about Black people and brown people and women that are not told by the people who have lived these stories, and to deny their perspective is dangerous.”

Anika Poitier said she hopes the Sidney Poitier New American Film School will encourage students to tell their stories and provide a platform to share them.

“Because I think that it’s what the world needs desperately right now.”

Sydney Poitier Heartsong, an actor and producer, said that her father wanted Black people to have opportunities in all aspects of the film industry.

“I know at the time, the thing that angered him the most was that he was the only one. He was the only one standing up there. He was the only one with an Academy Award. And he fought so that others could be included as well,” she said. “He wanted to see his story and his likeness represented on the screen, and he was also keenly aware of the fact that that wasn’t going to fully happen, in the way that it should, unless there were people also behind the camera.”

Poitier grew up in the Bahamas and moved to New York as a teenager. Working as a dishwasher, he responded to an ad seeking actors for the American Negro Theatre.

In his 1980 memoir “This Life,” Poitier describes how, after a brief audition, he was rejected because of his strong Bahamian accent. So he bought a radio and listened to it constantly, mimicking the voices until he lost his accent. Six months later, he tried again and was accepted. He later discovered that he got in because not enough men had auditioned.

His first role was a small part in “Lysistrata” on Broadway. On opening night, he had such acute stage fright that he froze, bungling the lines. The audience laughed, and the newspaper review the next day praised his comedic talents.

After acting in road shows for a few years, Poitier went to Hollywood in 1950 to star in his first movie, “No Way Out.” He was 22 years old, playing a doctor who treats two white brothers who are racists, and was at ease in front of the cameras.

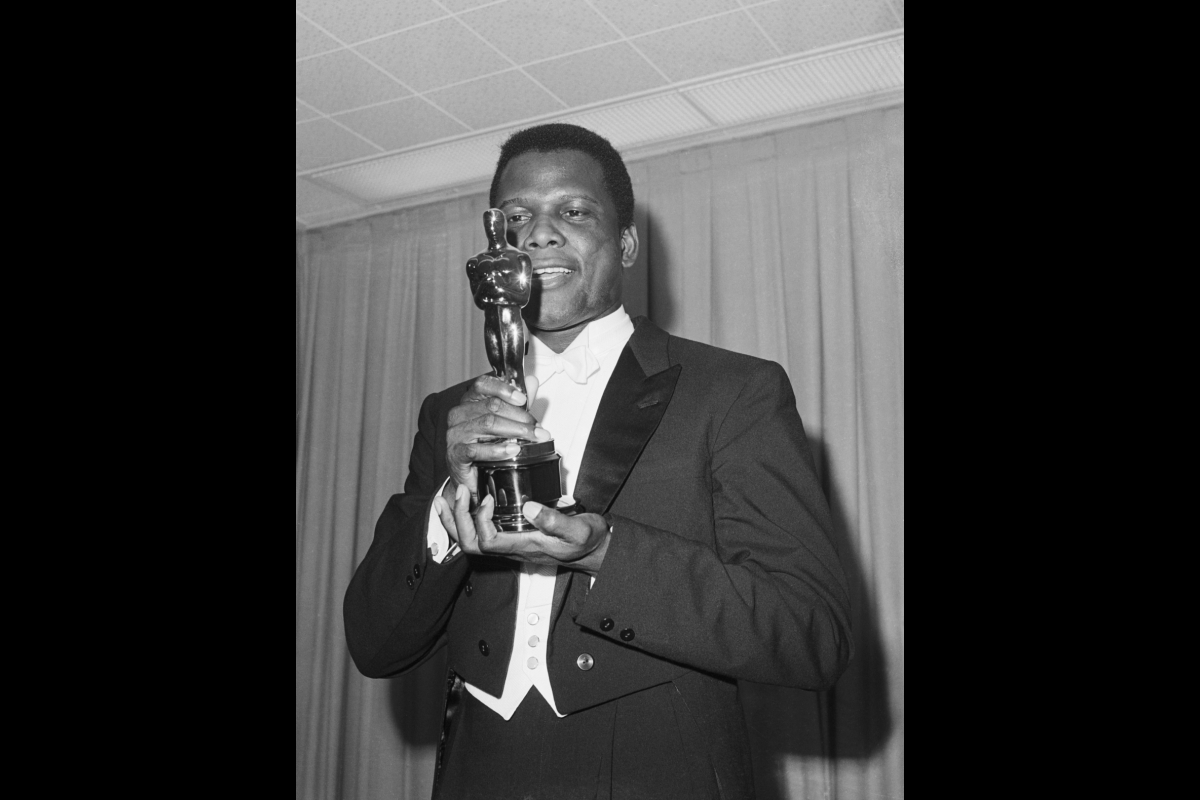

By 1958, he had starring roles. In “The Defiant Ones,” Poitier and Tony Curtis played escaped prisoners who were shackled together. Curtis requested that both of their names appear above the movie title. Both were nominated for best actor Oscars, with Poitier becoming the first Black man nominated. David Niven won that year for “Separate Tables.”

Poitier made a triumphant return to Broadway in 1960 in “Raisin in the Sun,” a play by Black playwright Lorraine Hansberry that he called “an uplifting experience.” He starred in the film version as well.

In 1963, Poitier traveled to southern Arizona to make “Lilies of the Field,” playing a handyman who reluctantly builds a chapel for a group of nuns. In “This Life,” Poitier says little about his time in Arizona except that the movie was on such a tight budget the shooting schedule was condensed into a fast two weeks.

Poitier won the best acting Oscar for his role. In his memoir, he recounted his reaction: “I was happy for me, but I was also happy for the ‘folks.’ We had done it. We Black people had done it. We were capable. We forget sometimes, having to persevere against unspeakable odds, that we are capable of infinitely more than the culture is yet willing to credit to our account.”

Poitier’s blockbuster year was 1967, in which three of biggest hits were released: “To Sir, With Love,” in which he plays an engineer teaching a rowdy group of students in London’s East End; “In the Heat of the Night,” playing a police detective investigating the murder of a white businessman, and “Guess Who’s Coming to Dinner,” in which Poitier’s character is engaged to a white woman. All of the movies directly addressed racial issues.

In “This Life,” Poitier wrote about his career slowdown in the 1970s, and the backlash over his many distinguished characters — often the only Black character in a movie filled with white people: “A Black man was put in a suit with a tie, given a briefcase; he could become a doctor, a lawyer or police detective. That was a plus factor for us, to be sure, but it certainly was not enough the satisfy the yearnings of an entire people. It simply wasn’t.”

He stayed away from Hollywood during the heyday of Black exploitation films (mostly made by white men), which he saw as only temporarily satisfying to Black audiences, who would eventually want movies that reflected their lives better than a doctor or a hustler.

That’s where he saw the role of comedy. In “This Life,” he described screening “Uptown Saturday Night,” the third movie he directed, to a roomful of white production company executives in 1974. After the movie ended, there was an awkward silence from the group, who didn’t know what to make of its joyful depiction of Black humor and camaraderie. It was a huge hit.

Poitier returned to Arizona twice as a director. When he was directing “Stir Crazy” in 1980, Columbia Pictures wanted to rent what was then called the Arizona State Prison in Florence. The warden agreed and used the money to build a rodeo arena. More than 300 inmates signed on to be extras in the movie.

Two years later, Poitier returned to Tucson to direct “Hanky Panky.”

Poitier acted in fewer films in the 1980s and ’90s, adding roles in TV movies and shows, including portrayals of Thurgood Marshall and Nelson Mandela.

He served as the Bahamian ambassador to Japan from 1997 to 2007.

WATCH: The naming celebration for the Sidney Poitier New American Film School

More Arts, humanities and education

Exceeding great expectations in downtown Mesa

Anyone visiting downtown Mesa over the past couple of years has a lot to rave about: The bevy of restaurants, unique local shops, entertainment venues and inviting spaces that beg for attention from…

Upcoming exhibition brings experimental art and more to the West Valley campus

Ask Tra Bouscaren how he got into art and his answer is simple.“Art saved my life when I was 19,” he says. “I was in a dark place and art showed me the way out.”Bouscaren is an …

ASU professor, alum named Yamaha '40 Under 40' outstanding music educators

A music career conference that connects college students with such industry leaders as Timbaland. A K–12 program that incorporates technology into music so that students are using digital tools to…