Increased political polarization found to thwart global environmental goals

The latest UN climate summit — the 26th edition of the “Conference of the Parties,” or COP26 annual meeting — ultimately delivered on its primary goal of keeping alive the Paris Agreement’s aim to limit global warming to 1.5 degrees Celsius (2.7 Fahrenheit) above preindustrial levels.

Nations agreed on the Glasgow Climate Pact, which states that carbon emissions will have to fall by 45% by 2030 to keep alive the 1.5-degree goal.

Charles Perrings

But according to new research led by School of Life Sciences Professor Charles Perrings, it may become even harder for nations to reach a consensus within this modern era of increased political polarization.

“What we found is that polarization leads to greater treaty non-compliance. It's more difficult to negotiate and sustain international agreements, the more polarized the electorate is and the more polarized political parties are,” Perrings said.

At Arizona State University, Perrings directs — along with School of Life Sciences colleague Ann Kinzig — the ecoSERVICES Group within The College of Liberal Arts and Sciences. The group studies the causes and consequences of change in ecosystem services — the benefits that people derive from the biophysical environment.

Perrings led a team that viewed international environmental agreements from this big-picture perspective.

Environmental treaties

Michael Hechter

In a new research study published in the Proceedings of the National Academy of Sciences, a team comprising Perrings, ASU political scientist Michael Hechter, a professor in the School of Politics and Global Studies, and Robert Mamada of Grand Canyon University used a complex adaptive systems approach to analyze the effect of polarization on national compliance with international environmental treaties.

Complex adaptive systems occur when the seemingly uncoordinated responses of nation-states adapt to changes in the conditions addressed by particular environmental agreements. These changes may generate seemingly coordinated patterns of behavior at the level of the system.

For the study, they considered how polarization of political parties and stakeholders on the issues addressed by international environment agreements affects commitment to those agreements.

There have been more than 3,600 International Environmental Agreements (IEA) since the 19th century. Of these, the big majority (80%) represent bilateral agreements: 10% involving 10 or fewer signatories, and less than 1% involving 100 or more signatories. According to Perrings, this network of IEAs has been characterized as a complex adaptive system in which, in the absence of international controls, simple behavioral rules at the national level may give rise to complex international adaptive dynamics.

The network of treaties has evolved from a single node (treaty) in 1857 to 747 nodes with 1,001 directed links by 2012 — with waves of increased activity following the 1972 United Nations Conference on the Human Environment (the Stockholm Conference) and the 1992 Earth Summit (the Rio Conference).

Fanning the flames

The complex adaptive systems approach sees decentralized interactions between nation-states pursuing their own agendas on particular issues as a potential source of seemingly coordinated adaptive behaviors across the network.

The approach anticipates the emergence of herd-like adaptations to changes in environmental conditions as a function of the topology of the system.

“The simplest analogy would be to the way that a forest fire spreads,” Perrings said. “If you think about a forest area as a set of pixels, then there are well-defined relations governing combustion within and between the individual pixels. Each one has a very simple relationship to the next, but the spread of the fire across multiple pixels may be very, very complicated.”

However, within politics, the fire spreading is an increased political polarization that leads to less diversity of opinion, and less ability to reach consensus.

“It's a similar kind of thing when we look at human behavior,” Perrings said. “Individuals are interacting — very often through social media — and those interactions can generate at the level of a wider system.

“Interactions between individuals in a society that's polarized may be increasingly limited to those who share the same opinions. The social media they access then become echo chambers that amplify differences between groups.”

The softness of the law

Perrings notes that what environmental agreements have in common is that they are often unenforceable by international law.

“They are voluntary. And that's true, by the way, of all agreements. They're all self-enforcing,” Perrings said. “There's no supranational governing body that can wield a big stick, so they they're only as strong as the members of those agreements allow them to be.

“The reality identified in the literature is that the softness of the law embodied in most international agreements — the lack of enforcement or penalties — makes compliance largely optional. And it has long been recognized that nation-states do not want enforcement of agreements if they might themselves be noncompliant.

“In international law, there is no judiciary or police force to ensure compliance.”

The result is that countries can fail to meet their obligations or withdraw from agreements if they wish. For example, changes in the conditions confronted by member states of the European Union over the last two decades have strained the willingness to comply with EU agreements, leading the United Kingdom to withdraw from the union. And under the Trump administration, the U.S. opted to unilaterally withdraw from the Paris climate accord, only to reverse this decision with the current Biden administration.

In addition to changes in the environmental conditions addressed by the agreements, or changes in scientific understanding of the implications of those conditions, initial obligations in new agreements are frequently set low to induce countries to sign and then ratify those agreements. But if national obligations continue to increase, the effect will ultimately be to reduce national commitment by both parties.

“Even though the progression of obligations may be inherent in the initial terms of the agreement, mission creep can later trigger non-compliance, renegotiation or withdrawal,” Perrings said.

Existential threats

How much of the environmental crisis is seen as an existential threat by the nations that govern the response? Perrings notes that even during the great threat of the current COVID-19 pandemic, one might have been expected a coordinated international disease control effort under the World Health Organization. But the immediacy of the threat to national populations led to an almost the polar opposite — a wholly decentralized response to the pandemic.

“What many nations did was to devolve responsibility as fast and as far as they could — to individual states, cities and even municipalities. And they did so at a time when this is exactly the wrong thing to do,” Perrings said.

They found that if stakeholders are themselves polarized on environmental issues — as is the case with people’s view of climate change — there is less pressure on parties to narrow the gap between them, leading to a reduction in the commitment parties are willing to make to international agreements on those issues.

“Polarization leads parties to focus on an increasingly narrow set of issues, and an increasingly limited set of constituents. The main message becomes the exclusive focus. Parties start talking about one set of things, and talking to one set of people,” Perrings said. “At the level of the whole overall system, one of the things we've observed is that polarization leads to a loss of diversity in ideas, as well as in policies and policy instruments. The system becomes simplified around the core ideas associated with each of a relatively small number of groups.”

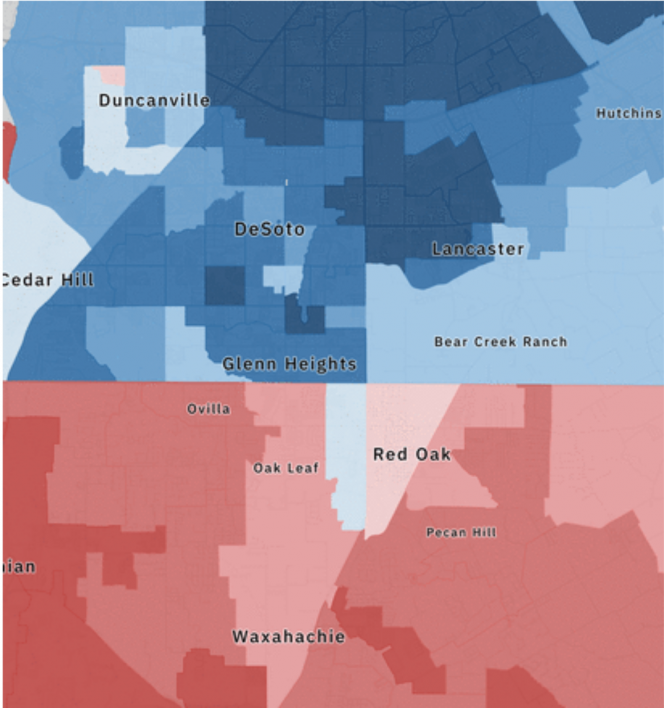

The 2016 U.S. presidential election results of Dallas, with precinct-level majorities for Republicans (red) and Democrats (blue). Image courtesy of Amanda Kmetz, Indraneel Purohit and Samuel S.-H. Wang of the Electoral Innovation Lab at Princeton University

Final thoughts

They draw two main conclusions. First, the rules governing national responses to changes in the conditions addressed by IEAs are not so simple after all.

Second, they found that stakeholder engagement has the capacity to moderate party polarization on the issues addressed by agreements, even where stakeholders are themselves polarized on those issues.

“An immediate implication of this is that if the electorate is to moderate party positions on agreements, they need a route to engage on those agreements. In the United States, the most direct route is via congressional elections, but that route is only available if the agreements themselves involve congressional action,” Perrings said.

The general cost of polarization is that it makes it more difficult to coordinate action to cooperate across groups to provide things of benefit to the wider public.

Polarization puts environmental issues and solutions off the table, and a range of consequences that are really quite significant are completely ignored.

“Whether the system is robust enough that it can adapt to environmental threats that are not being addressed is an open question. This should be one of the objectives of governments. You want to be able to survive the bad stuff,” Perrings said. “In the long run, we are all better off if 1,000 flowers are let to bloom.”

The germination of the project began from discussions between ASU and Princeton University faculty members as part of an ASU Dialogues in Complexity Workshop led by Simon Levin and supported by ASU’s Office of the President. Levin is a professor in ecology and evolutionary biology and director of the Center for BioComplexity at Princeton University.

“This is a new topic for me,” Perrings said. “I’m engaged in it is because of this initiative. Simon Levin was brought into a collaborative venture with ASU to look at the consequences of complexity.”

The research paper is part of an eight-paper PNAS special issue devoted to the topic. It also includes contributions from ASU’s Stephanie Forrest, whose research showed that common ground is shrinking in politics and people on opposite ends of the ideological spectrum are more entrenched in their divergent positions than at any time in recent history.

Already, the findings are generating a greater conversation on a national level and the media are taking notice, including a recent New York Times column.

Support for the research came from the National Science Foundation, the Army Research Office, the U.S. Defense Advanced Research Projects Agency and the Air Force Research Office.

Top photo by Deanna Dent/ASU News

More Law, journalism and politics

Peace advocate Bernice A. King to speak at ASU in October

Bernice A. King is committed to creating a more peaceful, just and humane world through nonviolent social change.“We cannot afford as normal the presence of injustice, inhumanity and violence,…

CNN’s Wolf Blitzer to receive 41st Walter Cronkite Award for Excellence in Journalism

Wolf Blitzer, the longtime CNN journalist and anchor of “The Situation Room With Wolf Blitzer,” will accept the 41st Walter Cronkite Award for Excellence in Journalism, Arizona State University has…

Cronkite School launches Women Leaders in Sports Media live-learn program

Women in a new sports media program at Arizona State University got a solid game plan from a sports veteran at an Aug. 20 welcome event.“Be humble, be consistent and be a solver,” Charli Turner…