High school sports is, for some people, emphatically not the glory days.

Endless drills and repetition. Riding the pine when you don’t get what coach has screamed at you. Watching the kids with some semblance of talent get all the attention.

Rob Gray’s new book, “How We Learn to Move: A Revolution in the Way We Coach & Practice Sports Skills,” wants to correct the way sports are taught and learned.

An associate professor at Arizona State University’s Human Systems Engineering program, Gray’s idea for the book came from his consulting work with sports teams. His research focuses on perceptual-motor control, with a particular emphasis on the demanding actions involved in driving, aviation and sports.

“We're changing how we think about how to train people and how we practice now,” Gray said. “The way I start the book is I kind of lament what I'm seeing with kids in sports. The way that we're doing it, a lot of things we're doing, I think it’s pushing a lot of people away ... I think not only does it kind of discourage people, but I think it can lead to them not developing a love of movement, of being active and causing health problems later on.”

In Gray's hands, how we learn and how we become skillful at a sport becomes something entirely different from the way we learned in high school.

That military idea that there’s one way to serve a tennis ball for example. That one way is to repeat that technique over and over until (theoretically) it’s automatic. You don’t play the game until you learn how to serve. Or dribble the soccer ball. Or sink a penalty shot.

“I think kids that can't learn the fundamentals — which can be boring — don't get a chance to enjoy the game,” he said. “And I find that kind of frustrating.”

With kids returning to sports after a long year spent kicking a soccer ball around in the back yard by themselves, coaches still have them dribbling balls around cones instead of playing together. It takes the fun out of learning to move and interact with your environment. Recent research shows that’s not the way we’re designed to do things, Gray said.

“We're not designed to repeat the same thing over and over,” he said. “We're designed to be adaptable to our environment and problem-solving and things like that. That's kind of the point that I'm trying to get across.”

One concept Gray demonstrates in the book is called self-organization. Coaches should not be instructors, but designers who create a practice environment where student athletes learn to figure out what works best for them.

“What I want to do is change the practice environment; for example, reducing the number of players or making you play on a smaller size field or changing the size of the ball to kind of encourage you to try different things and explore and figure out what works for you rather than, this is a way to do it, try to repeat this over and over," he said.

For tennis, play with lower compression balls and smaller rackets, so the ball doesn’t bounce as high. Let them actually play the game right away and experience variation.

In countries like Brazil, there aren’t a lot of facilities like you’ll find at the average suburban American high school. Kids play soccer in the street and on the beach, and with kids of different ages and sizes. But Brazil turns out some of the best players in the world, like Pelé.

“Instead of getting the kind of really high-class training facilities you can get in other countries, I argue, maybe that's an advantage,” Gray said. “It gives you a chance to learn to adapt and adjust to your conditions.”

In many sports, creativity — like making good decisions or creating opportunities to score — is crucial to playing well.

“But we don't give much chance in practice for people to develop that because we're telling you, here's what to do, rather than letting you figure it out,” he said. “Our body's not designed to do that. The body's really variable, you know. Even our heart rate... It's not like a metronome. It has variation in it.”

Gray hopes the book will inspire coaches to switch up training and practice, and parents to do the same when tossing the ball around the backyard.

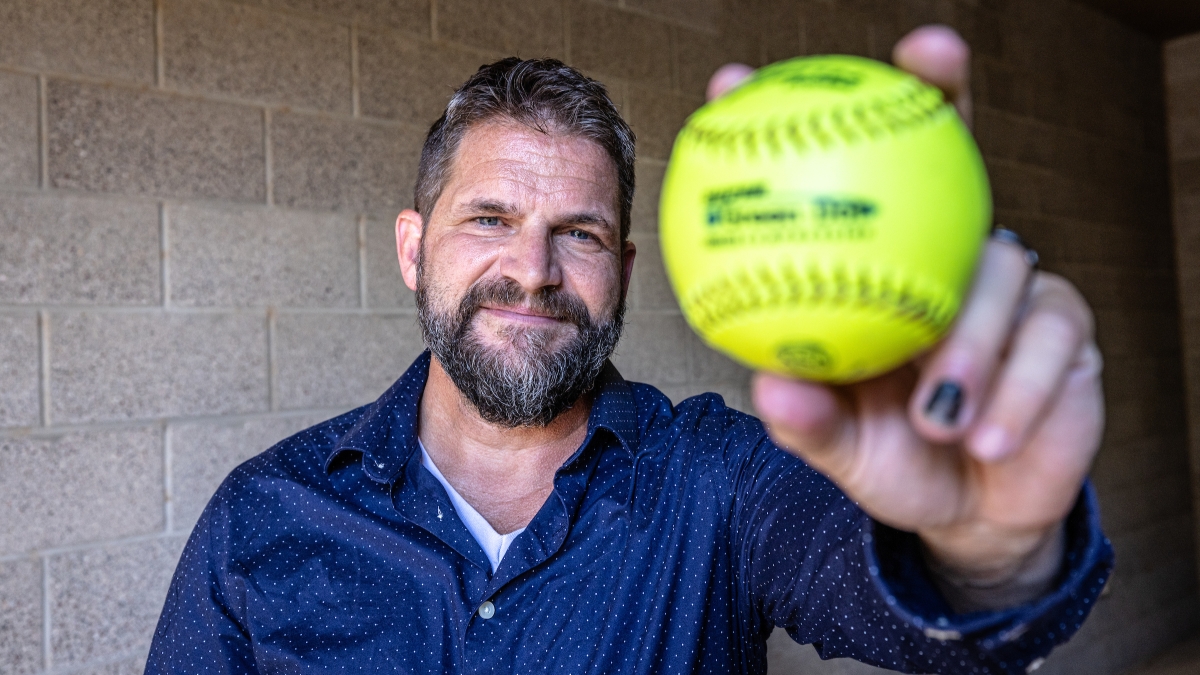

Top photo: Human systems engineering Associate Professor Rob Gray is photographed near his Santa Catalina Hall office on ASU's Polytechnic campus. Photo by Charlie Leight/ASU News

More Science and technology

Cracking the code of online computer science clubs

Experts believe that involvement in college clubs and organizations increases student retention and helps learners build valuable social relationships. There are tons of such clubs on ASU's campuses…

Consortium for Science, Policy & Outcomes celebrates 25 years

For Arizona State University's Consortium for Science, Policy & Outcomes (CSPO), recognizing the past is just as important as designing the future. The consortium marked 25 years in Washington, D…

Hacking satellites to fix our oceans and shoot for the stars

By Preesha KumarFrom memory foam mattresses to the camera and GPS navigation on our phones, technology that was developed for space applications enhances our everyday lives on Earth. In fact, Chris…