On Sept. 25, 1981, Sandra Day O'Connor was sworn in as an associate justice of the Supreme Court of the United States by President Ronald Reagan. She was the first woman to be appointed to the highest court in the land.

It was a milestone for her and for women in law across the country. On the 40th anniversary of that historic day, Sandra Day O’Connor College of Law at Arizona State University looks back at its namesake and the effect of her legacy.

Sandra Day O’Connor as a child. Courtesy of the O’Connor Institute

O'Connor, now 91, grew up on a remote ranch near Duncan, Arizona. A typical ranch kid, she branded calves with cowboys, rode horses everywhere, drove a pickup and was a crack shot with a .22 rifle. She learned to read by the time she was 4.

Later, she attended the Radford School for Girls in El Paso and graduated high school two years early. During that period, O'Connor's interest in the law was sparked from a family legal dispute over the ranch.

At 16, she was admitted to Stanford University and later was admitted to Stanford Law in 1950. She completed law school in just two years, graduating third in her class.

Attitudes toward women in law proved a barrier, and the imminently qualified Sandra Day O’Connor struggled to find a job. But she kept her nose to the grindstone and became the assistant attorney general for Arizona in 1965. Four years later, she made state headlines when she was appointed to the Arizona Senate.

In 1970, the state Legislature was very male and very rough. Raised among cowboys, she dealt with it by just walking away, according to Evan Thomas’ biography, "First: Sandra Day O'Connor." But sometimes she spoke up.

Tom Goodwin was the chairman of the Arizona House Appropriations Committee. Thomas described him as "a drunk-by-10 a.m. drunk." One day O'Connor called him out on it.

"If you were a man, I'd punch you in the nose," he barked.

"If you were a man, you could,” she replied.

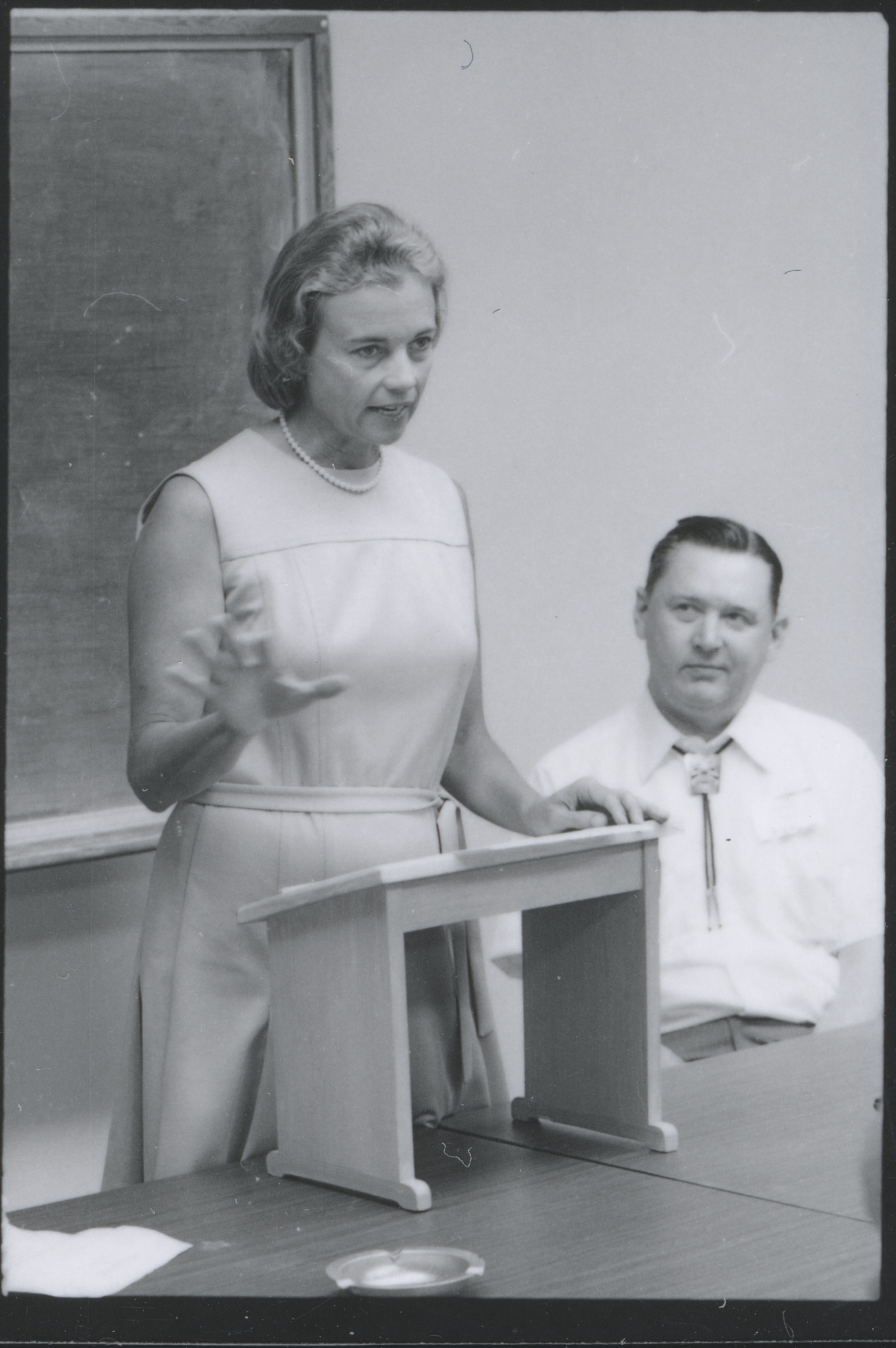

Arizona Sen. Sandra Day O’Connor speaks with the Taft Institute, likely at Arizona State University, circa 1974. Photo by Charles Conley/ASU

The milestones began to pile on for O’Connor when she became the first woman majority leader in any state senate in the United States. She was elected to the Maricopa County Superior Court in 1974, and appointed to the Arizona Court of Appeals in 1979, which positioned O'Connor for her historic appointment.

In July 1981, O’Connor became the first female justice in the more-than-190-year history of the Supreme Court.

O’Connor’s legal decisions were often the swing vote in divisive cases. She tackled issues such as gender discrimination, abortion rights, sexual harassment and freedom of religion. Known mostly as a conservative justice and a proponent of judicial restraint, O’Connor also developed a reputation as an independent thinker and voter.

She retired from the bench in January 2006 to care for her ailing husband, who was diagnosed with Alzheimer’s disease. That April, ASU Law was officially renamed the Sandra Day O’Connor College of Law.

“While the final chapter of my life with dementia may be trying, nothing has diminished my gratitude and deep appreciation for the countless blessings in my life,” she wrote in a letter released by the Supreme Court’s public information office. “As a young cowgirl from the Arizona desert, I never could have imagined that one day I would become the first woman justice on the U.S. Supreme Court.”

Roslyn Silver, a federal judge for the U.S. District Court for the District of Arizona, has known O’Connor for decades.

An ASU Law alumna, Silver started at the school in 1968.

“There were very few women in any of the classes,” Silver said. “I think we had five women at the time.”

When she walked into the school, one of the upperclassmen warned her that there were no women's restrooms in the building. He explained she would have to walk across campus to the nearest facility.

"And initially I believed him, though he was joking,” she said. “That lawyer better not appear in my courtroom now, I can tell you.”

Silver never thought the professors treated women differently.

“If you performed, it didn’t make any difference what your gender was,” she said.

One of her fondest memories was working on the law review. But a professor told her the school was not ready for a woman to be editor-in-chief.

“That’s the only negative thing that happened to me,” she said. “Other than that, as hard as I worked, I still had a good time.”

In 1974, O’Connor was chair of the state Senate Judiciary Committee. They had proposed a memorandum that would have declared that life was created at conception. The National Organization for Women objected to that. They asked Silver to speak on their behalf. She appeared before O’Connor.

“She was very firm in her questions, but polite,” she said. “I frankly was terrified, but I got through it.”

They met on the street sometime later. Silver introduced herself.

“She was very friendly, and she invited me to come to her courtroom and watch her,” Silver said. “She was very well-prepared and asked very good questions. No question she was in control of the courtroom. ... She was not shy about scolding lawyers when they were unprofessional.”

O’Connor had experience in ways that Silver said you don’t see on the Supreme Court; she was a trial lawyer and she had state court experience. And she had some political experience: “All of that worked very well for her.”

“I also recognized — quietly, I guess — that this marked the opening of doors for women,” Silver said. “It expanded the opportunities for women throughout the United States on the judiciary and frankly for women lawyers. It meant to me that all women who were qualified and determined were valued, and could be rewarded in this country. It would be difficult to deny women if they were determined to succeed. So in my view she’s a hero for women.”

Sandra Day O’Connor leads a lecture on Sept. 19, 2005, at ASU. Photo courtesy of the Sandra Day O'Connor College of Law

Reflecting the trailblazing nature of O’Connor’s career, only 2% of law students were women at the time she attended in the 1950s. By the time she retired in 2006, that percentage had risen to 48 percent. For the ASU Law incoming fall 2021 JD class, women and nonbinary students make up nearly half of the class.

Kate Rosier is the assistant dean for institutional progress at the college and executive director of the Indian Legal Program. O’Connor’s legacy inspires her now.

“She's witty and passionate and spunky,” Rosier said. “And I think that her legacy shows that she didn't back down to any type of challenge. It's really impressive.”

Rosier works with Native attorneys and the Native population in her role with the Indian Legal Program.

“We've just had our first Native dean: Stacy Leeds, who's on the ASU Law faculty,” Rosier said. “But we have our first Native woman as a federal judge with Diane Humetewa. The first secretary, Deb Haaland. Right? And so I feel like (O’Connor) did a lot of work for women, and she's inspiring because we see that as what is possible for the rest of the groups of color. You know, she fought hard to open a lot of doors, and the rest of us are working hard to make sure we keep them open, to help change what the profession looks like.”

When O’Connor was on the Supreme Court, she was noted for mentoring her clerks and making sure they were well connected, so they got good jobs after they left her office. Sometimes she cooked dinner for them.

That welcoming tradition is carried on today at the school that bears her name.

Sandra Day O'Connor poses with Sparky at an ASU event in 2013.

“One of the things that I've heard the dean say is she's a very fun and kind woman,” Rosier said. “And we want the students to feel that as well in the environment of the law school. I feel like her presence has a place in the law school, even though she isn't in the law school with us.”

Mentorship is key to being successful, especially for first-generation students and those without connections to the profession.

“We try to connect students in a lot of different areas, whether Indian law trying to connect you with Native attorneys, or if you're a woman, try to connect you with women in the profession,” Rosier said. “And we just started a first-generation program to make sure that they understand and have friendly people to ask questions to because without those people in place, you know, it's hard to be successful and know where to go to help for help. And so I think our law school is making everybody feel welcome and supported along this journey.”

Courtney Moore, a first-year law student this fall, saw that spirit of helping when she came to visit the school.

“When I came to visit ASU for my tour, when I was trying to determine if I want to be at Sandra Day O'Connor College of Law I was met with so much welcome,” Moore said. “They took me to lunch. They took me on a tour around the school. ... And when I left and I visited some other schools, I didn't see that. And so that was one of the reasons why I moved all the way out here to attend the school, because I felt that sense of community.”

Moore is part of the Advance Program. In furtherance of the ASU Charter, the goal of the program is to foster an inclusive community at ASU Law, particularly for first-generation students, students of color and students who have overcome adversity. It’s a yearlong program bringing together a cohort of 20 students who can offer different perspectives from ethnic, cultural, religious and other backgrounds.

“It's the networking that I've been able to have, the connections that I've been able to make, and I've only been here for a little over three weeks,” Moore said. “And it all started with the Advanced Scholars program, being able to be brought in with other underrepresented communities, first generation just in general, just being able to connect with them and then be matched to an actual mentor, a student mentor, and an attorney mentor through that program. ... It's been an incredible experience so far.”

Retired Supreme Court Justice Sandra Day O'Connor laughs as ABOR Chair Greg Patterson recalls his time at the university during the grand opening of the Beus Center for Law and Society, home of ASU's Sandra Day O'Connor College of Law, on the Downtown Phoenix campus Aug. 15, 2016.

Rosier said she is proud to have O’Connor’s name on the building and to work at an institution that supports her legacy.

“We're trying to do everything we can to support our students and make sure that if somebody graduates with a degree from this fine institution, that they're going to be great practitioners and hopefully change the world like she did,” she said.

Top photo: Sandra Day O'Connor Being Sworn in a Supreme Court Justice by Chief Justice Warren Burger (left) swears in Sandra Day O'Connor as a Supreme Court justice as her husband watches on Sept. 25, 1981. Photo by White House Photographic Office/National Archives

More Law, journalism and politics

Can elections results be counted quickly yet reliably?

Election results that are released as quickly as the public demands but are reliable enough to earn wide acceptance may not always be possible.At least that's what a bipartisan panel of elections…

Spring break trip to Hawaiʻi provides insight into Indigenous law

A group of Arizona State University law students spent a week in Hawaiʻi for spring break. And while they did take in some of the sites, sounds and tastes of the tropical destination, the trip…

LA journalists and officials gather to connect and salute fire coverage

Recognition of Los Angeles-area media coverage of the region’s January wildfires was the primary message as hundreds gathered at ASU California Center Broadway for an annual convening of journalists…