A group of Arizona State University students explored the intersection of art and science and found astounding beauty.

In the “Art and Science” course, students work with faculty members in the School of Life Sciences and the Biodesign Institute. One of the assignments is to find an object that can viewed under an electron microscope, where the hyper-resolution produces extraordinary images.

Then the students produce artworks inspired by their discoveries. The dramatic pieces created by the students who took the course during spring semester will be exhibited in the show “Sculpting Science,” which will run Aug. 19 to Aug. 28 at the Step Gallery, Grant Street Studios in Phoenix.

“Art and Science,” offered every other year, is taught by Susan Beiner, a professor in the School of Art and internationally known ceramic artist, in collaboration with science faculty members, including Robby Roberson, an associate professor in the School of Life Sciences who creates the electron microscope images.

“It started as a way for students to use microscopy to make artwork and it’s really evolved into this collaboration with the School of Life Sciences and the Biodesign Institute,” Beiner said.

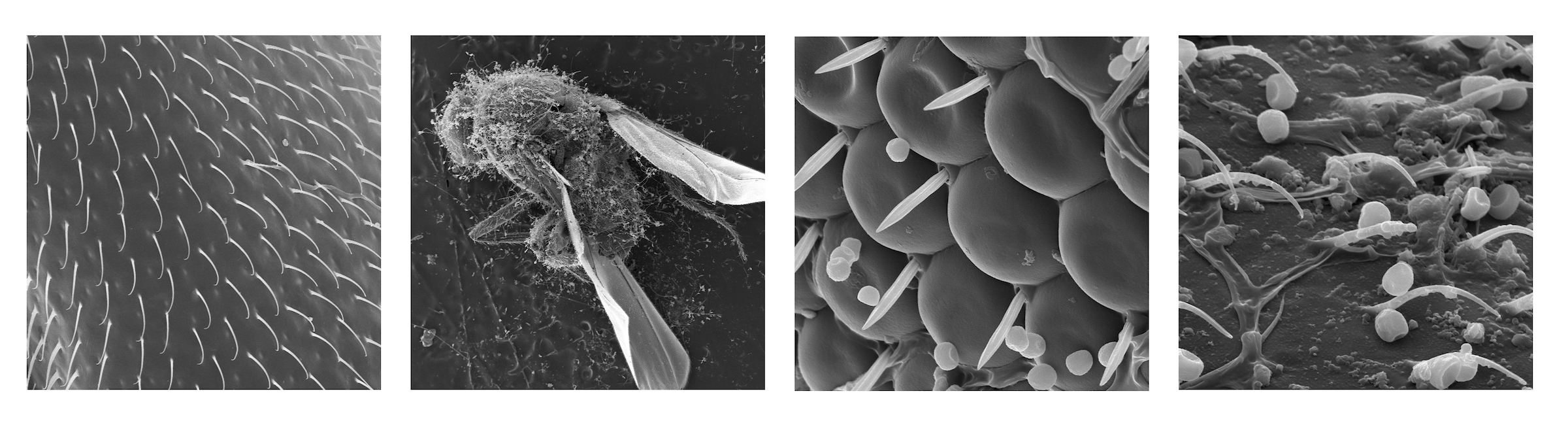

These are the images of a dead fruit fly taken by Associate Professor Robby Roberson through an electron microscope and used by student Sara Faye.

The students visit several research labs over the semester and then learn about microscopy from Roberson.

“The students bring him objects and then get about 12 images from that,” Beiner said.

“What they give to him and the scans they get back are very different. And then they create an art object from the scanned image.”

Students have scanned everything from leaves to hair to popcorn and can create their projects in any medium.

“We’ve had metal work, mixed media, painting, and a lot of students feel they have to do ceramics because I’m in ceramics,” Beiner said.

“One student created a project where she embroidered cells and we’re hanging them from a steel rod, like a microscopic view. It’s the first time I’ve had anyone think about translating science into a fiber material.”

The course ended in May, but because the projects are so intense, Beiner holds the exhibit at the beginning of the fall semester, so students have extra time to refine them.

“Art and Science” is open to undergraduates and graduate students of any major. Over the years, more science students have participated, Beiner said.

“Some of the things the science students come up with are not what the art students come up with.

“They’re not as connected to art, so they think in different ways, and sometimes it’s more innovative in terms of how it relates to the content.”

Student Sara Faye (left) and Professor Susan Beiner work on Faye's sculpture for the "Art and Science" show, based on electron microscope images of a fruit fly. Photo by Deanna Dent/ASU News

Sara Faye, a senior who is a biology major with a focus in cellular genetics, worked in a fly lab on campus when she took the course. So she gave Roberson a dead fly to scan.

“I do quite literal things, so for my project I built a fly lying in a dish,” she said. “The fly was covered in a fungus so I covered my fly with dead baby’s breath flowers to emulate the fungus, which is life growing from death.”

Faye said that Beiner emphasized how the creative process and the scientific method can power each other.

“You have to be creative in science and you have to be clinical in art, where you test new ideas over and over to see if they’re right,” said Faye, who is minoring in studio art.

“It took me hours of testing to make sure I had the right glazing and right material to put on my piece.”

Adam Sanders made a ceramic vase based on electron microscope images of a mummified gecko’s foot.

“The toes are segmented and they have these tiny little hairs on them, and I found out that it’s these hairs that make geckos stick to the wall,” he said.

“So I made a great big vase based on the segments of the gecko’s toes.”

Alumnus Adam Sanders and Professor Susan Beiner examine his nearly completed piece based on the structure of a gecko's toes. Photo by Deanna Dent/ASU News

Sanders also made two other pieces for the show.

“One was based on conversations we had about molecular biology and cellular biology,” he said.

“I learned about the coronavirus and, more importantly, the vaccine and how it teaches your immune system to identify the virus without actually having to put the virus inside your body. Your immune system practices on that and when the coronavirus comes, it knows what to do.”

Inspired, he created a ceramic piece.

“I put gold leaf on it so it’s fancy,” he said.

His other piece is based on a talk with a geology professor.

“It turns out this big layer we thought was homogenous between the Earth’s mantle and core is made of these semi-fluid, irregularly shaped blobs,” he said.

“My piece is made of brass and I cast this acrylic blob inside of it and I think it won’t be like anything else in the show.”

Susan Beiner works in her home studio on a piece that will eventually be displayed in the Memorial Union on ASU's Tempe campus. Photo by Deanna Dent/ASU News

Sanders graduated in May with a Bachelor of Fine Arts in sculpture and is now working on a piece of public art to be installed next year. He had to work with his adviser to arrange for his scholarship to cover last spring’s “Art and Science” course, which is considered a science credit.

“I worked hard to take that class,” he said, especially because he was eager to learn from Beiner, who recently won the grand prize in the prestigious Taiwan Ceramics Biennale.

Sanders found that “Art and Science” expanded his point of view.

“My dad was a geologist so growing up, science was a big part of my life, and as an artist, it might seem like those two don’t intersect. But in reality, as a sculpture major, everything I do is science.

“When I’m making a mold of something, it’s a chemical reaction. If I’m welding, it’s using electricity to melt steel together at 1,500 degrees.

“The more I do art, the more I realize how intertwined it is with science.”

Top image: Adam Sanders, who took the "Art and Science" course during spring semester, works on one of the pieces that will be shown in the "Sculpting Science" art show. Photo by Deanna Dent/ASU News

More Science and technology

ASU-led space telescope is ready to fly

The Star Planet Activity Research CubeSat, or SPARCS, a small space telescope that will monitor the flares and sunspot activity of low-mass stars, has now passed its pre-shipment review by NASA.…

ASU at the heart of the state's revitalized microelectronics industry

A stronger local economy, more reliable technology, and a future where our computers and devices do the impossible: that’s the transformation ASU is driving through its microelectronics research…

Breakthrough copper alloy achieves unprecedented high-temperature performance

A team of researchers from Arizona State University, the U.S. Army Research Laboratory, Lehigh University and Louisiana State University has developed a groundbreaking high-temperature copper alloy…