ASU professor's new book 'Appleseed' transcends genre

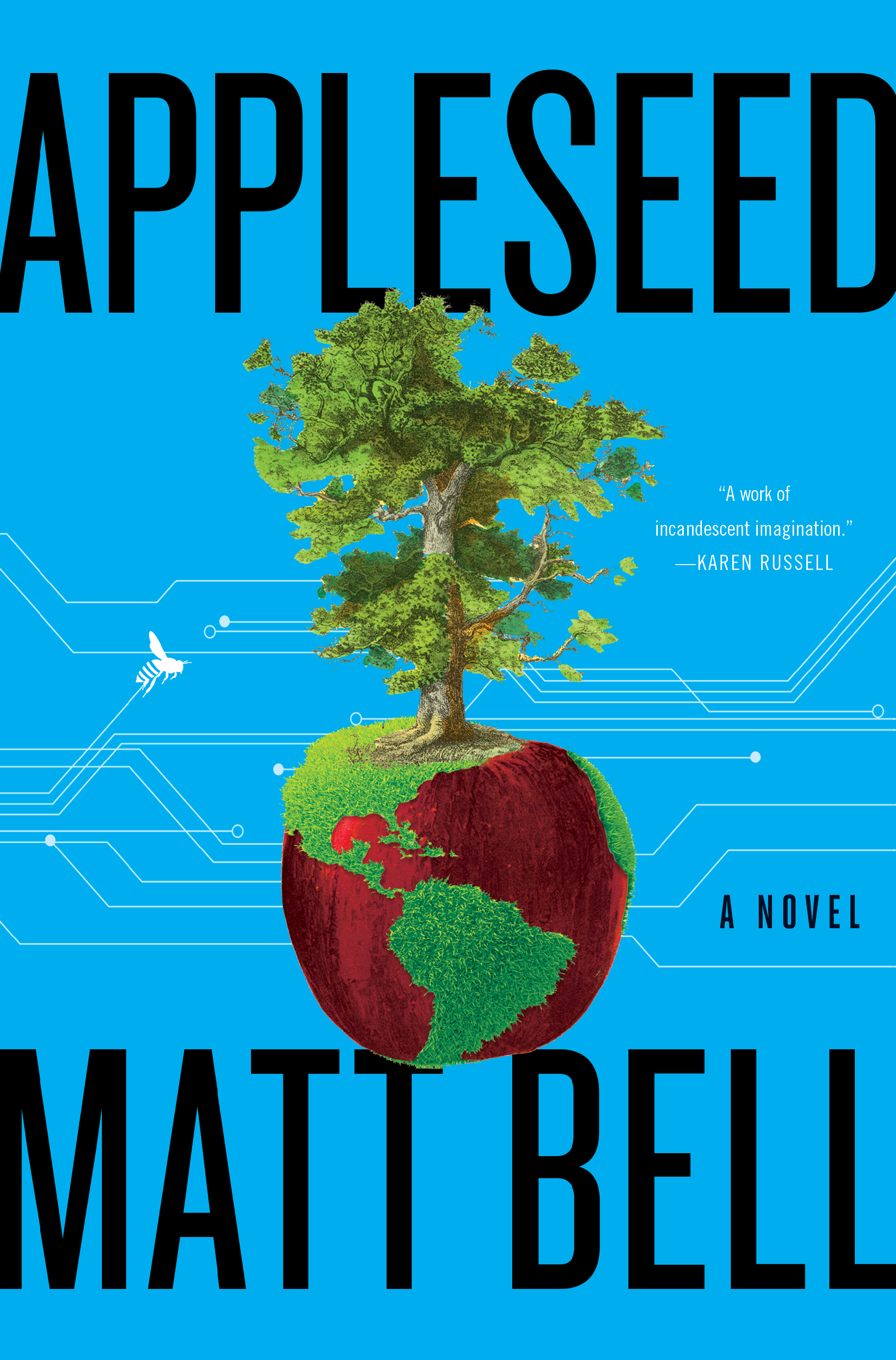

Matt Bell, associate professor in Arizona State University’s Department of English, released his latest book, “Appleseed,” this month — a speculative fiction book that explores themes of climate change, humanity’s unchecked exploitation of natural resources, familial responsibility, manifest destiny and the magic contained within every apple. Photo by Jessica Bell.

One of Matt Bell’s goals as a novelist is to write at least one book in every genre he loves. In his latest book, “Appleseed,” Bell transcends genre with a story that is equal parts fantasy and science fiction.

MORE: Books by the ASU community

“I initially set out to write a fabulist, mythological retelling of the Johnny Appleseed folktale, inspired by a line in Michael Pollan's ‘The Botany of Desire,’ but it quickly started sprawling through time,” said Bell, associate professor in Arizona State University’s Department of English.

“Appleseed,” released this month, is a speculative fiction book that explores themes of climate change, humanity’s unchecked exploitation of natural resources, familial responsibility, manifest destiny and the magic contained within every apple.

The story begins in 18th-century Ohio, where two brothers plant apple orchards from which they plan to profit in the years to come. The story then fast-forwards to 50 years from present day, in the second half of the 21st century. Climate change has ravaged the Earth and as one company owns all the world’s resources, a growing resistance is working to redistribute both land and power. Finally, Bell takes the reader 1,000 years in the future, where North America is covered by a sheet of ice and one sentient being sets out on a quest to discover the last remnant of civilization.

“Writing a story that takes place in three different time periods meant I had to find a way to ground the reader in three different realities, none of which were exactly ours. That required a lot of invention, most of it driven by what I thought was interesting or cool or weird or fun or generative of more story,” Bell said. “Populating a mythical past with shapeshifting witches and a half-human Johnny Appleseed was just as much fun as inventing bioengineering rigs and swarms of nanobees and glacier-crossing bubblecrafts; on the best days, I'd write something that surprised me entirely, discovering something I never imagined might exist even in a world of my own making.”

Bell said his students provided inspiration for his work. He first began writing “Appleseed” in 2016, alongside students in his novel-writing workshop in The College of Liberal Arts and Sciences’ creative writing master’s degree program. Three years later, he finished the main draft of “Appleseed” with another novel-writing class.

“It's a lucky thing to be surrounded by so many talented student writers here at ASU, and I'm sure my conversations with them in and out the classroom about the stories they were writing helped push mine along too,” he said.

The book has received high praise and recognition, including in The New York Times, USA Today, Esquire, local National Public Radio affiliate KJZZ, The Boston Globe, Literary Hub and more.

Bell shared more about his process, challenges he encountered while writing and the inspiration behind “Appleseed.”

Question: What did your process look like for writing “Appleseed?”

Answer: I started writing Appleseed in October 2016 and did the final edits almost exactly four years later. As for my usual process, I generally try to write a couple hours a day, at least every weekday. My ideal would be to write from breakfast to lunch, which I do as often as I can. It's not the most exciting thing to watch, probably. It's mostly slowly and steadily piling up the pages, figuring out the story a little bit at a time, researching and revising as I go.

Q: Did you encounter any challenges when working on the book?

A: One of the hardest problems to solve was the near-future storyline, because writing a future close to our own time requires more plausible cause and effect than writing something further in the future does. One of the inspirations for the political situation in that timeline came from Naomi Klein's “The Shock Doctrine,” which is about the rise of disaster capitalism – it helped me imagine how a corporation might use the climate crisis to seize vast amounts of power and capital. In the novel, a company calls Earthtrust does just this, taking control of half of the United States and eventually much of the world's food supply, which emboldens them to try to make unilateral decisions about the future of the planet, including an attempt to geoengineer the stratosphere. It was an interesting scenario to figure out — and also one I hope never comes true.

Q: You’ve written several other books. How was working on “Appleseed” similar and/or different?

A: One hard truth about a career as a novelist is that no matter how much you've already published, the book you're writing doesn't know you've written other books, so there are always ways in which it's the first time, even when it's the third or fifth or 30th … I'm assuming on that last one. Finishing a novel always feels impossible until suddenly it isn't, and there isn't much I've found to speed that process along. That said, each book's challenges tend to be unique, which is challenging but also part of the fun. In the end, the best way to learn to write the book you're writing is to keep writing it, and eventually the solutions to even the thorniest problems tend to appear, either on their own or by the suggestions of early readers and editors.

Q: What do you hope readers take away from the book?

A: I don’t want to interpret the book for readers, because I really think that novels function best when they serve as experiences for readers to enjoy and think about and feel through on their own, without the author's interference. But I do hope the novel provides a space for readers to think about the relationship between the human and nonhuman worlds, and about what kind of futures we want to make together. One of my own focuses when I was writing was to try to capture my own wonder at the natural world as often as I could, in every timeline, in hopes that it might create the capacity for more wonder in the reader: I truly believe that our wonder at the world is a necessary component of our want to save it, that it's partly wonder that reminds us why the world is worth saving.

More Environment and sustainability

2 ASU faculty elected as AAAS Fellows

Two outstanding Arizona State University faculty spanning the physical sciences, psychological sciences and science policy have…

Homes for songbirds: Protecting Lucy’s warblers in the urban desert

Each spring, tiny Lucy’s warblers, with their soft gray plumage and rusty crown, return to the Arizona desert, flitting through…

Public education project brings new water recycling process to life

A new virtual reality project developed by an interdisciplinary team at Arizona State University has earned the 2025…