Hoping to win the lottery? That would actually be a wish you have. Hoping to have a good day today? That’s being optimistic.

According to social science researchers in Arizona State University’s Center for the Advanced Study and Practice of Hope, having hope is harder work than we may think. They are unpacking the ways in which different populations conceive of hope and exploring how having higher hopes can improve our health and well-being.

What hope means

In psychology, hope is a cognitive practice that involves the intentional act of setting goals and working toward them with purpose.

“Hopeful people are able to set goals, identify ways to reach their goals and feel as though they can do the work to achieve those goals,” said Crystal Bryce, associate director of research in the Hope Center and clinical assistant professor in the T. Denny Sanford School of Social and Family Dynamics.

John Parsi, executive director of the Hope Center, thinks about using hope like driving from ASU’s Tempe campus to the Downtown Phoenix campus.

“If there’s an accident on the I-10 or construction on the Broadway curve, I have to work around that to get to my destination. I can’t just stop in the middle of the highway and give up,” said Parsi. “I have to navigate through the traffic using hope theory and ultimately take agency to literally steer my actions.”

Parsi emphasizes that it is important to know the difference between hope and blind optimism.

“Hope is an active process. Dreams and optimism are just belief structures,” he explained. “When you’re an optimistic person, you believe things in the world will turn out just fine, no matter what happens.”

Parsi says that because optimism doesn’t require a person to do anything, it can be a form of toxic positivity. But from the working scientific definition of hope, hope can only do good for a person.

“Hopeful people cannot just wish things into existence,” he said. “Hope requires a person to take responsibility for their wants and desires and take action in working towards them. Optimistic people see the glass as half full, but hopeful people ask how they can fill the glass full.”

Hope in higher education

One of the center’s ongoing projects is exploring what hope looks like in populations of ASU first-year students. Research has shown that more hopeful students are better off in terms of their health and ability to tackle future challenges.

“Students that have more hope do better in school, have more developed social and emotional skills, and foster stronger connections with their peers,” said Ashley Fraser, a PhD student in the Sanford School and member of the Hope Center research team.

“The strategy of hope is fairly robust in its real-world impact. This isn’t a squishy science,” said Parsi. “Increased hope has been shown to be more effective than many mental health interventions in youth populations. Even as experts in this field, we get surprised time and time again by the impact and results these hope interventions have on the populations they are implemented in.”

The team places special emphasis on hope research in college students because positive psychology in the college experience is generally understudied.

“If you look at most studies around college students, historically it is really negative,” said Fraser. “Researchers often look at drinking, drug use, suicide and pregnancy, all of these negatively associated outcomes. Part of our center’s objective is to show that this is a great time in young people’s lives. This is really a time where people can change the course of their lives if they want to.”

The team’s data shows that first-year students with high hopes in their first semester of college were more likely to enroll in a second year than students with low hope. Increased hope in these students is also associated with prosocial behavior, better civic attitudes and increased community engagement in college.

In the next stage of this study, the team wants to see how students’ levels of hope affect their well-being and social-emotional skills.

“The data has shown that the first year of college is a really great intervention point,” said Bryce. “We could really target first-semester students and teach them how to cultivate their hope. Some of them might not even know that hope is teachable. We are trying to develop exercises and practices for first-year students in fall 2021 to instill hope skills into their lives and see what impact this support has.”

Building hopeful communities

Many of the Hope Center’s other research projects revolve around the Kids at Hope, an affiliated nonprofit committed to working with youth-serving organizations to cultivate a culture of hope in community settings. The partnership allows researchers in the center to work with practitioners in the community and translate research into real-world impact.

“The hope research field is already fairly small,” said Parsi, who also serves as president of Kids at Hope. “But even rarer is this combination of a robust research center at a leading university and a nonprofit organization outlet to exercise our research and collect data from. It truly is a special partnership.”

In Michigan's Macomb County, the ASU team has been working with the state’s juvenile justice system to investigate how probation officers, educators and administrators within the incarceration community view and promote hope in youth on probation. Kids at Hope and the Hope Center team have also partnered with the Saddle Mountain Unified School District in Tonopah, Arizona, to see how hope practice curriculum can be integrated into schooling and how it impacts student relationships, engagement and achievement.

“Our lives are holistic. We are more than our work and more than our families, so we must set goals in all areas of our lives,” said Parsi. “This often starts with small goal setting and breaking down big goals into smaller, more reachable interim goals.”

In their hope curriculum, Kids at Hope teaches practitioners three universal truths:

- Every child — no exceptions — is capable of success.

- Connection between adults and youth is meaningful and impactful.

- Goal setting happens in many areas, including education and career, home and family, community and service, and hobbies and recreation.

“Everyone in these communities sees the glimmers of hope and understands how important it is to the success of their youth, but they’re not quite sure how to increase hope or support that kind of culture,” said Bryce. “That’s where we come in with our research on socialization to further their goals as organizations.”

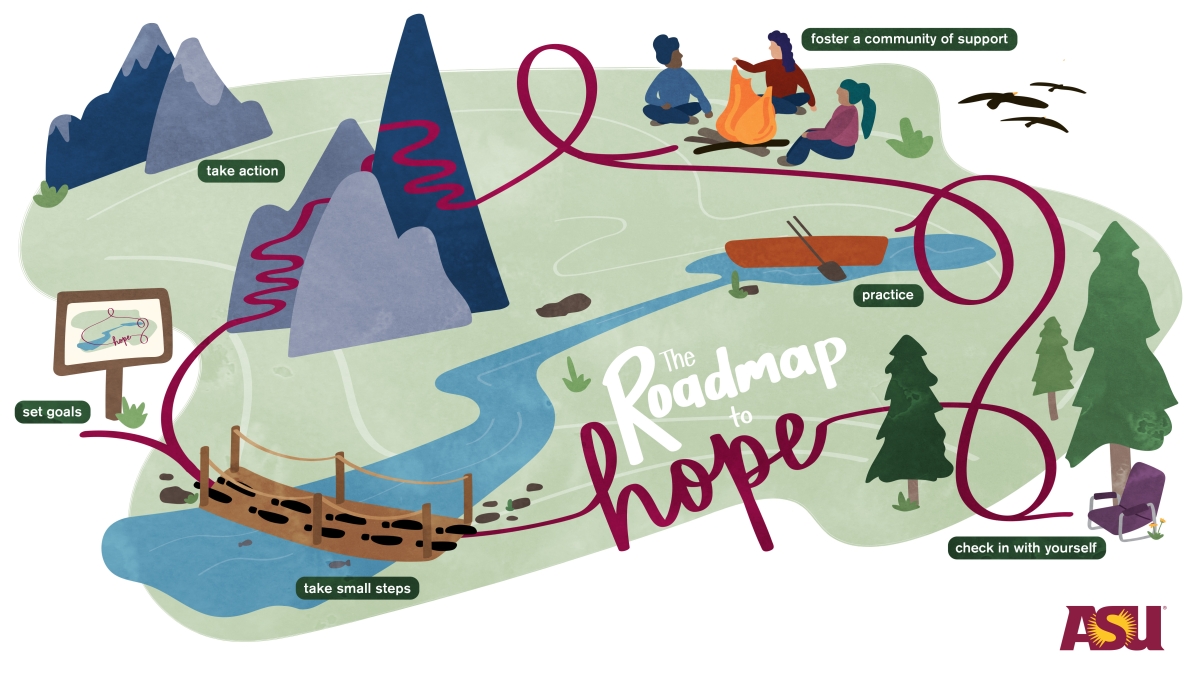

How to have hope

Though they are experts on the theory of hope, Bryce, Fraser and Parsi are always working to become more hopeful people themselves. They offer some tips to help you get your hopes up in ways that benefit you and your community.

1. Take small steps for long-term success.

“Think about your goals for just today and make a list of actions that you need to do to accomplish those goals,” said Fraser, a self-proclaimed “hopeful realist.” “Then, envision your larger, long-term goals and see how your actions today will help you achieve those bigger, broader goals you have for yourself.”

2. Check in with yourself.

If you aren’t excited and enthusiastic about taking the next step in reaching your goals, odds are your goal needs to be adjusted.

“Ask yourself if you’re excited about the future ahead of you and if your actions leading you there have energy behind them,” said Fraser. If you can answer “yes” to these questions, then it’s a good sign you are developing hope, according to hope theory.

3. Consider context.

The team encourages people to consider the cultural context they live in when evaluating how hopeful they are. Some of the center’s research revolves around how different ethnic populations, specifically Hispanic and Latino communities, view and practice hope.

“We do see something similar to hope in every culture. Part of that is because the human condition is designed to look forward,” explained Fraser. “The conception of hope looks different in religious communities, though the outcomes are still overwhelmingly positive. Hope is also a big positive impact in medical patient communities.”

In Fraser’s previous research, she investigated hope among post-war Colombian youth. She found that young people exposed to violence and trauma experienced a decrease in hope. Systemic oppression that is out of a person’s control can lead to uncontrollable feelings of hopelessness.

“It’s important to understand that in some populations, we cannot just say ‘be more hopeful’ because there are contextual and cultural factors that can really hinder a child’s hope,” said Fraser. “Though hope does cross borders, there is more to discover about hope in the face of adversity.”

4. Remember that hope takes practice.

Even the researchers studying hope admit that they don’t always practice what they preach to others.

“Hope is really hard. There are times where I don’t have as much hope as I want to,” said Bryce. “When I’m teaching a class or applying for grants, I constantly find myself trying to find those small steps to get to the larger goals I want to fulfill at the moment. We have to constantly remind ourselves of this, though we are entrenched in it all the time.”

In 2018, Parsi’s wife suffered a series of strokes. The couple had to pick up everything they had in Alaska to move to Arizona so that she could receive treatment at Barrow Neurological Institute.

“We had to be hopeful to get through that, but I definitely have my ebbs and flows,” said Parsi.

“Life-altering events, like the ones that happened in my life, really force a person to take a step back and reevaluate the toolkit that we approach life’s challenges with. For me, that meant prioritizing different things in my life and setting new goals for myself.”

5. Foster a culture of hope.

The researchers at ASU’s Center for the Advanced Study and Practice of Hope emphasize that hope thrives within communities that support and uplift one another.

Parsi had trouble fostering hope in educational and social contexts of adversity. As the son of immigrants, a non-native Engish speaker and a first-generation college graduate, he often faced racist and xenophobic individuals and systems throughout his professional career.

“There would be a lot more people who overcame adversities in the world if we created a culture that values hope as a priority and invests in children and their ability to create,” said Parsi.

As a hope researcher and community member, Parsi feels responsible to be a part of the success and failures of all the people in the communities he belongs to.

“It is my responsibility not to pull the ladder up behind me, but instead to let the hardships I went through inform the idea that the success of our children belongs to all of us,” he said.

Written by Maya Shrikant

Top illustration by Ashley Quay

More Health and medicine

ASU grad dreams of helping hometown residents with a career in family medicine

Eliu Zaragoza When Eliu Zaragoza was in high school, he found himself especially drawn to his science and math courses. He appreciated that the STEM field wasn’t…

ASU grad finds purpose in serving her community through emergency medical services

Isabella Lirtzman Growing up in Scottsdale, Arizona, Isabella Lirtzman always knew she wanted to stay close to home for college. Her decision to attend Arizona…

What to know about Arizona’s measles outbreak

Arizona now has the second-largest outbreak of measles in the nation this year. Arizona State University’s Health Observatory has launched Disease Insights, a website that includes up-to-…