Mapping Liberia for western chimpanzee conservation

ASU researchers alongside Conservation International are working to help determine future potential protected areas for the critically endangered western chimpanzee. Photo courtesy of depositphotos.com

Deep within Liberia’s dense rainforests lives one of the most intelligent and threatened species on the planet: the western chimpanzee.

Extremely social and one of human’s closest relatives, this mammal develops unique strategies suited to their environment, from crafting spears for hunting to gathering in caves to cool off, socialize and sleep.

In the last 25 years, the western chimpanzee (Pan troglodytes verus) population has declined by more than 80% and was recently reclassified by the International Union for Conservation of Nature (IUCN) from an endangered species to a critically endangered one.

Habitat loss and deforestation due to logging, urban development, mining and other natural resource extraction are this exceptional species’ biggest threat, and, as Africa’s human population is estimated to double in the next 30 years, therein lies new challenges for wildlife conservation.

In order to make crucial land-use decisions across the country, managers will need to better understand the makeup of western chimpanzee habitats at large spatial scales, including how potential habitats connect with one another for breeding, where they fall in relation to existing protected areas and if there is overlap with current land use for agriculture, industry and infrastructure development.

Newly published ASU research led by Amy Frazier, associate professor in the School of Geographical Sciences and Urban Planning, and Miroslav Honzák, a senior science director at Conservation International and a former professor of practice at ASU, tackles this critical data gap.

“By quantifying the value of nature, you can give people the information that allows them to make decisions to protect it,” said Frazier, who conducted the research in collaboration with Conservation International, administered through the Global Futures Laboratory. “We aimed to look specifically at not only where (chimpanzees) were located but also to determine whether those habitats were connected so chimpanzees in one area can physically reach other chimpanzees in another area, and then ultimately look at where those areas were in conjunction with some of the conservation priority areas in Liberia.”

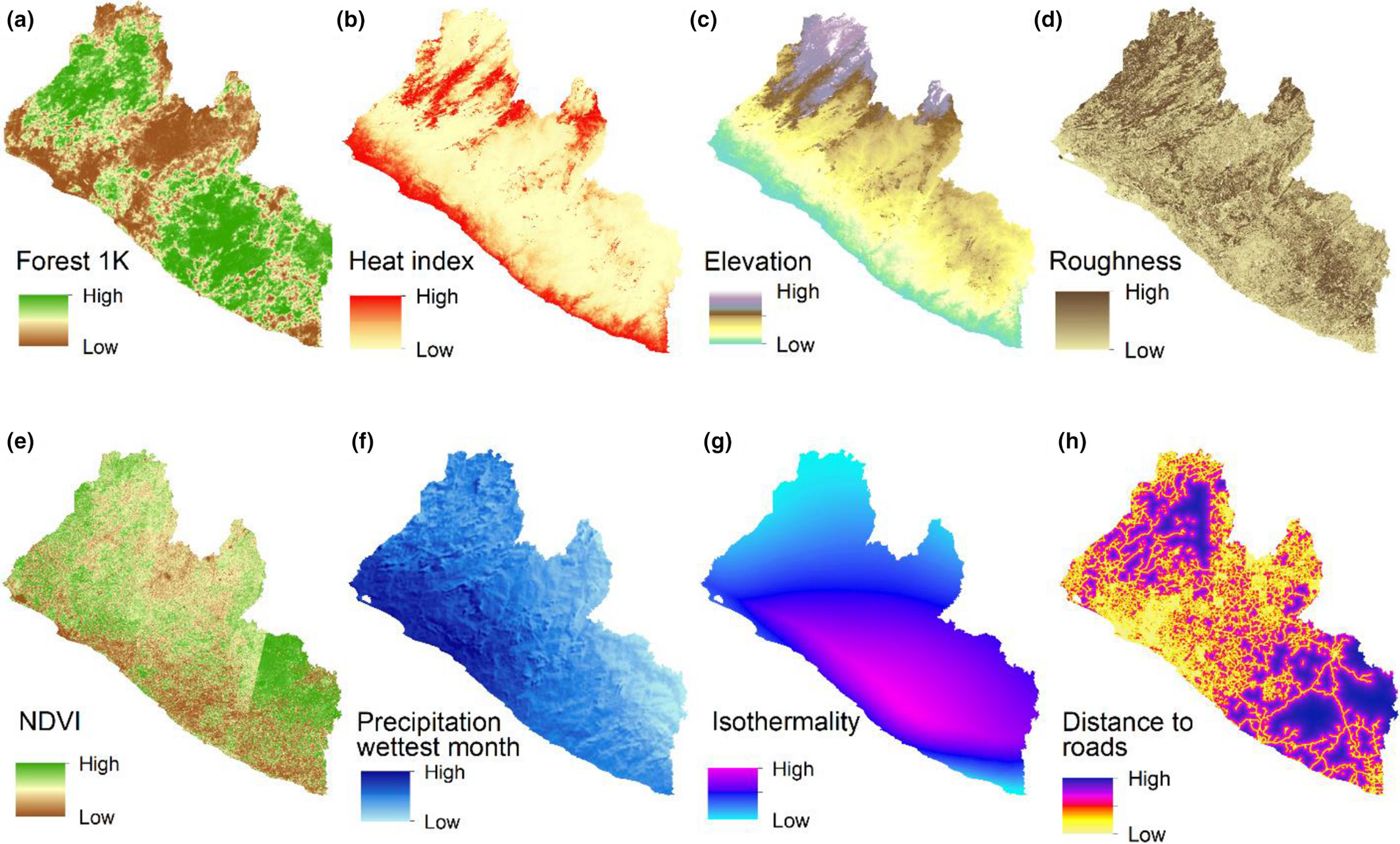

In their research, published in the journal Diversity and Distributions, Frazier and her team — which included Andrew Trgovac, lecturer in the School of Geographical Sciences and Urban Planning, and Master of Advanced Study in Geographic Information Systems students — analyzed and compared more than 40 layers of data spanning remotely sensed geographic information, chimpanzee occurrence points and climate variables to best understand chimpanzee habitat suitability and connectivity across Liberia.

They then produced a series of detailed maps visualizing the areas most suitable for western chimpanzees, how the areas are connected with one another and where they overlay with existing protected areas and areas currently earmarked for natural resource extraction.

“Direct observations and surveys of species cost time and money, and certain areas can be difficult to access for various reasons such as harsh environments, rugged terrain or they are simply unsafe,” said Frazier, who is also the associate director of ASU’s Geospatial Research and Solutions. “Species distribution models allow us to map where species might exist now (and in the future), given what we know about their habitat preferences, in order to produce credible information to inform conservation decision-making.”

Examples of eight of the environmental indicator variables used for modeling.

As one of the study’s key findings, researchers found that primary forest cover (specifically the amount of primary forest within 1 km, 2 km and 3 km of a chimpanzee occurrence) was the most important predictor of chimpanzee habitat suitability at all spatial scales.

“We found that more than anything else, more than any other variables, more than climate or elevation or population, the amount of forest is what really determines where we find chimpanzees,” Frazier said. “If we can protect primary forest, that will be a good start for conserving western chimpanzees.”

Also in the study, Frazier and her team found that several important corridors for chimpanzee habitat and movement overlap significantly with existing timber and palm oil extraction sites. Mining and rubber concessions overlapped critical habitat to a lesser degree.

“We found that a lot of these really important areas of connectivity are not currently being preserved, and they are not even in the areas being proposed for preservation,” Frazier said.

With a better spatial understanding of western chimpanzee habitat suitability and connectivity, this research can play a critical role in aiding the way land managers and decision-makers rethink conservation priority.

“It’s helpful to use this information in concert with other information the Liberian government may be using to determine future potential protected areas,” Frazier said. “This work is one step toward conserving the biodiversity of Liberia and aiding Liberia's conservation planning goals of conserving the value of nature.”

This research was done as part of a collaboration between ASU and Conservation International to protect nature and train the next generation of conservation leaders. ASU and Conservation International began partnering in September 2016 with the hire of six ASU-Conservation International professors of practice to drive collaborative research and education on global conservation. The partnership has since evolved to align with the ASU Global Futures Laboratory.

More Environment and sustainability

Arizona Water Innovation exhibit highlights 1,000 years of ingenuity, connection

In Arizona, water and innovation are inseparable. From the ancestral O’odham canal systems that carried water from the Salt…

How integrating nature can make cities more equitable

More than 80% of people on Earth now live in cities and towns, which means that urban areas have a huge role to play in solving…

ASU grad dedicated PhD to uncovering evolutionary relationships between their favorite creatures: Weevils

When Alexis Cortes Hernandez was an undergraduate student, they were determined to become a botanist. But then, they crossed…