Deep under the ocean, microbes are active and poised to eat whatever comes their way

Elizabeth Trembath-Reichert running the winch for the CTD water sampler, which was used to bring fluids up to the ship from the bottom of the ocean. Photo by Ben Tully

The subseafloor constitutes one of the largest and most understudied ecosystems on Earth. While it is known that life survives deep down in the fluids, rocks and sediments that make up the seafloor, scientists know very little about the conditions and energy needed to sustain that life.

An interdisciplinary research team, led by ASU and the Woods Hole Oceanographic Institution, sought to learn more about this ecosystem and the microbes that exist in the subseafloor. The results of their findings were recently published in Science Advances, with ASU School of Earth and Space Exploration geobiologist and Assistant Professor Elizabeth Trembath-Reichert as lead author.

To study this type of remote ecosystem, and the microbes that inhabit it, the team chose a location called North Pond on the western flank of the mid-Atlantic Ridge, a plate boundary located along the floor of the Atlantic Ocean.

North Pond, at a depth of over 14,500 feet (4,420 meters) has served as an important site for deep-sea scientists for decades. It was most recently drilled hundreds of feet through the sediment and crust by the International Ocean Discovery Program in 2010 to create access points for studying life and chemistry beneath the seafloor.

With support from the National Science Foundation, the Gordon and Betty Moore Foundation, and the Center for Dark Energy Biosphere Investigations, the team sampled the crustal fluid samples from the borehole seafloor observatories with the deep sea remotely operated vehicle Jason II on the research vessel Atlantis.

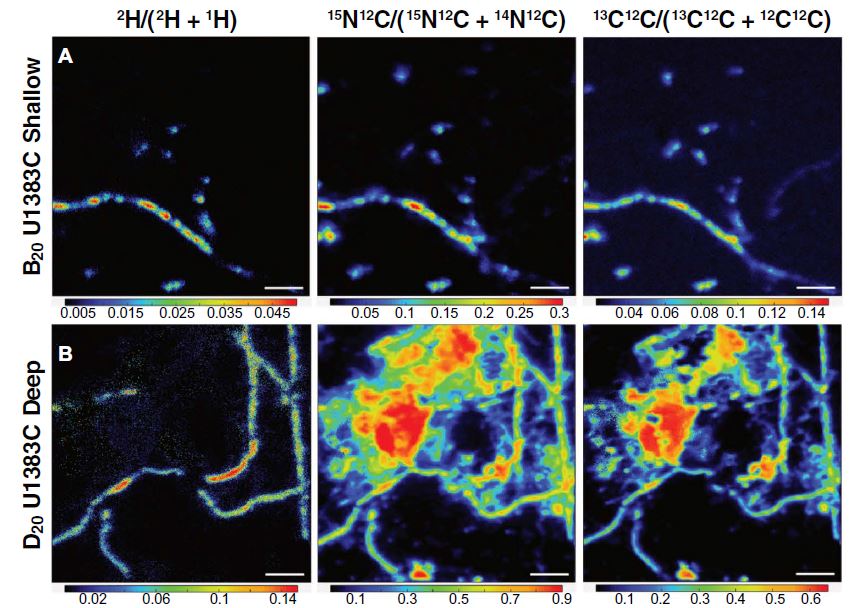

These unique samples from the pristine, cool basaltic seafloor were then brought back to the lab and analyzed using a nanoscale secondary ion mass spectrometer (NanoSIMS), which was used to measure their elemental and isotopic composition.

“Our experiments use specialized tracers that can only be observed if a microorganism eats something on the buffet of options we provide,” Trembath-Reichert said. “If we see these tracers in the microbes, then we know they must have been active and eating during our experiments and we get an idea of what food sources they can use to survive.”

Trembath-Reichert with Olivia Nigro from Hawaii Pacific University on the research vessel Atlantis after the first fluid samples (in the clear plastic boxes) came on deck from the borehole seafloor observatories. Photo Credit: Kelle Freel

Through these analyses, the team discovered that the subseafloor microbial community is active and poised to eat, despite an environment with low biomass and low-carbon conditions.

“The microbes we studied are extremely adaptable and are able to make a living in what seems like a really harsh environment to surface dwellers, like ourselves,” Trembath-Reichert said.

One of the most surprising discoveries was how the microorganisms use carbon dioxide. Trembath-Reichert and her team expected the microorganisms to use widely available carbon dioxide the way plants do, by "fixing" it into other forms of organic carbon that they can then use to grow on. But the findings suggest the microbes in this isolated environment with low nutrients were being more crafty.

“Our theory is that these microbes are being resourceful and using the carbon dioxide directly as a building block without having to convert it into a food source first,” Trembath-Reichert said. “And this could have major implications for the deep ocean carbon cycle.”

"This work highlights how little we know about the lifestyle of microbes within oceanic crust and the importance of carrying out experiments with sensitive detection limits, such as NanoSIMS,” said senior author Julie Huber, of the Woods Hole Oceanographic Institution.

The first ever single-cell NanoSIMS images from this system were used to show what food sources microbes (pictured here) used. Warmer colors indicate more of a certain food source was used. 3 μm scale bar.

The next steps for Trembath-Reichert and her team are to design experiments to better understand the full diversity of ways carbon dioxide can be used by microbes. As a more readily available food source for microorganisms, they will be looking into the ways carbon dioxide can be used for survival and growth in the Earth's largest aquifer beneath the seafloor.

To conduct this research, Trembath-Reichert was supported by fellowships from the NASA Postdoctoral Program and the L’Oréal For Women in Science Program.

Additional authors on this study include Sunita Shah Walter of the University of Delaware, Marc Fontánez Ortiz of ASU’s School of Life Sciences, Patrick Carter of the University of Massachusetts and Peter Girguis of Harvard University.

More Science and technology

ASU in position to accelerate collaboration between space, semiconductor industries

More than 200 academic, business and government leaders in the space industry converged in Tempe March 19–20 for the third annual…

A spectacular celestial event: Nova explosion in Northern Crown constellation expected within 18 months

Within the next year to 18 months, stargazers around the world will witness a dazzling celestial event as a “new” star appears in…

ASU researcher points to fingerprints as a new way to detect drug use

Collecting urine samples, blood or hair are currently the most common ways to detect drug use, but Arizona State University…