The English Renaissance ended nearly 400 years ago, yet the people and creative works of that era can tell us a lot about ourselves today.

At Arizona State University, a rich body of experts study literature from this period, and they’re finding surprising insights. How have our emotions changed? Why don’t we say “thou” anymore? How long has Shakespeare had his own fandoms? What do humble paper pushers have to do with the entertainment industry?

As we look forward to a future after COVID-19, the Renaissance is also a useful case study on how a society changed after a pandemic — in this case, the Black Plague — and how artists thrived through the period’s recurring epidemics.

The Black Plague was a pandemic that ravaged the world from the 1330s to 1352, killing an estimated 30% to 60% of the European population alone. When it arrived in England in 1348, it sparked many societal changes that helped spur the Renaissance movement. This refreshed period saw the rise of an educated middle class and an accompanying interest in science, the arts, global exploration and new theologies and ideologies.

ASU Renaissance researchers offer some insights on William Shakespeare, the star of the English Renaissance, the intriguing time period that shaped him and what it means for our lives today.

Big mood

Some of our notions about our feelings are the same as in the Renaissance, while others have changed. Description: Portrait of Sarah Bernhardt as Hamlet, 1899.

Bradley Irish, an associate professor in the ASU English Department, studies historical emotion in Renaissance literature with insights from modern neuroscience. He’s currently writing a book about disgust in Shakespeare’s works.

When it comes to how people think of their emotions, some things were slightly different during the Renaissance, Irish said. For example, today, envy means wanting something that someone else has.

“Back then, they also thought of envy as a general form of malice. They used the term envy much more expansively,” he said. “It's the same concept of the word, in the same basic formulation, but how and where it gets deployed is different.”

Similarly, Irish describes disgust as the emotion of rejection, which hasn’t changed since Renaissance times. However, the way we relate to disgusting objects varies across time and place. Differences in hygiene and sanitation, for example, meant that people in the Renaissance had a different relationship to the material side of the human body than many of us do today.

Although the emotional moments that Renaissance people wrote about have long since passed, Irish believes the topic has value because it helps us explore how literature engages our emotions.

Emotion is the key to understanding how all art works.

“And it's not just literature. All forms of art evoke our emotion, whether it's visual art, music, anything really,” he said. “Emotion is the key to understanding how all art works.”

Will there be a change in our own emotional expression after the COVID-19 pandemic? The last year was certainly marked by a range of emotional experiences. Irish says that in the future, it could be interesting to study what kinds of emotions carried us through COVID-19 and the impact they had on us.

“Are things like the way that we react to other human bodies in the world going to be different a year from now, even if we're all vaccinated and things have died down? Is it going to change the way we view our interactions with strangers?” he asked. “Those are fundamentally emotional questions on emotional orientation towards other people. It wouldn't surprise me if some of that definitely changed.”

Wouldst thou subscribe to my channel?

Valerie Fazel, an instructor in the English Department, explores the works of Shakespeare found in an unexpected place — mainly YouTube, along with Tumblr, Reddit and other corners of the internet. The fandoms that create this content, however, go back further than the internet itself.

YouTube commenters influence other viewers much like Renaissance audience members did each other. Description: 1642 print of the Globe Theatre in London, by Wenceslas Hollar.

“Today we have a lot more avenues to witness fandom, but we can talk about Shakespeare's 1623 folio as being a work of fandom. It was composed by publishers because they were fans of Shakespeare's performances,” she said.

One of the outlets that fans have found to share their passion in recent times is YouTube, although those expressions have evolved since the video-sharing site got its start in 2005.

In YouTube’s early days, people would create mashups that combined their favorite scenes from Shakespeare films with popular songs, Fazel explained. As websites grew stricter about copyright enforcement, these videos were replaced by a wave of high school and local performances. Now, and especially during pandemic restrictions, she sees more professional organizations and theaters creating their own channels to publicize their work.

Fazel has also observed some similarities between live audiences in Shakespeare’s time and the YouTube comments section, which she writes about in a recent essay in “Shakespeare’s Audiences.”

“If you're ever at a play and all of a sudden the audience starts laughing, most people kind of laugh along, even though they're not sure if they got the joke or even if they heard the joke,” she said. “This kind of audience impact also takes place on the YouTube comment forum. When someone posts a comment, it influences the viewers of the video and other people's comments as well.”

We should try to dismantle some of the notions that we have had all along about the Renaissance, because there is more to learn.

While Fazel appreciates Shakespeare’s works, she believes we can learn more by asking new questions of them, such as those around race and identity, rather than by putting them on a pedestal.

“They are texts that we should be able to analyze and use in ways that matter to us now,” Fazel said. “We should try to dismantle some of the notions that we have had all along about the Renaissance, because there is more to learn.”

MORE: Read about research on Shakespeare and race from another ASU expert, Regents Professor Ayanna Thompson

One particular trend has emerged from the pandemic — Shakespeare fans are reading and creating more than ever before as they embrace social connections online.

Right now, Fazel is exploring whether the content from this new surge of fan fiction is different in any way from other works of the past. One of the things she finds interesting about studying fan work is that it almost immediately responds to what’s taking place in a fan’s world. She believes it is important to record these snapshots of historical moments and experiences.

“I think one of the responsibilities as somebody who does fan scholarship is to archive this work in my own research,” she said.

'He made it up' is made up

He doth protest too much? Shakespeare didn’t invent tons of English words as popular myth would have us believe. Description: Otto Kruger in the play “Will Shakespeare,” 1923.

As a linguist, Professor Jonathan Hope studies how English has been used throughout the past, with a special focus on language in Renaissance literature. Hope is the director of literature in the English Department.

One of the biggest myths about English that he constantly debunks is that Shakespeare invented many of the common words we use today.

“There's this idea that because he's a great writer, he must have influenced the language. And it's just not true,” Hope said. “Individuals don't invent languages. Languages are kind of like group projects.”

He argues that what Shakespeare did well was capture the breadth of the language of his time. As the globe became more connected during the Renaissance, English began to borrow more words from other languages. Playwrights in particular were quick to adopt the latest words from Italian, Spanish and French.

“People want Shakespeare to be this kind of amazing genius, but he's just good at using words. He uses the language better than anyone else,” Hope said.

There are a few theories about how the Black Plague might have affected English and produced the language of Shakespeare’s time, Hope says, but it’s difficult to say for certain if the plague was the true cause of one change or another.

Languages are kind of like group projects.

One theory is that the plague led to the disappearance of the pronoun “thou” from everyday English. Many European languages have two forms of the second-person pronoun, one to be polite and formal, one to be familiar and informal. English used to have “you” as the formal pronoun and “thou” as the informal pronoun.

Some researchers believe that as workers became scarce during and after the Black Plague, people started using “you” for everyone in order to get into workers’ good graces and hire them. The problem with the theory is that the plague happened all across Europe, but English is the only language that experienced this phenomenon. Hope believes that the plague probably did affect English, but in ways that were much more subtle.

Will the current coronavirus pandemic similarly influence language? It’s possible.

“The current pandemic clearly is having effects on how people interact and how people speak,” Hope said.

He’s noticed that during lessons hosted over Zoom, his students will hold themselves back because the platform doesn’t handle multiple people talking at once, which has made class discussions a challenge.

Hope explains that during in-person conversations, we rely on complex physical and verbal cues to tell when someone is about to start or stop speaking. Those cues are much harder to pick up in virtual conversations.

“There's a whole lot of complex things that allow us to have quite fast interactive conversations when we're together in the same room,” he said. “On Zoom, you don't really get those, so it makes everyone slightly uncomfortable in conversation. But I don't know whether that will have any lasting effects on conversation afterwards.”

Some achieve greatness

During the late 1500s, the English government needed more workers who were educated and literate. To supply them, the country provided free public schooling to middle-class boys. Up to that point, education was reserved for the rich and those training to work for the church.

Shakespeare was one such boy to gain from this new opportunity, and he received training in language, literature, rhetoric and history.

“Of course, what happened was a lot of the brightest young men of the period got that education and then thought, ‘I don't actually want to be a government official. I want to use those linguistic gifts more creatively.’ And so it was that the entertainment industry began in Shakespeare's time,” said Sir Jonathan Bate, an ASU Foundation Professor of Environmental Humanities in the School of Sustainability. In addition to sustainability, he researches both how Shakespeare’s culture influenced him and how he shaped the cultures that came after him.

Performances for diplomats to the English court exposed Shakespeare to other peoples and cultures, inspiring “Othello,” which has a person of color as the titular character. Description: “The Return of Othello” by Thomas Stothard, ca. 1799.

As England got its first permanent theaters, playwrighting and acting became viable careers, and royals became fans. Shakespeare’s acting company played for the court at special occasions like diplomatic events, which in turn exposed Shakespeare to different cultures.

“For example, around 1600, there was a North African delegation of diplomats, known as Moors, who arrived to negotiate with Queen Elizabeth, and Shakespeare performed for them,” Bate said. “Seeing these fantastically sophisticated North African diplomats gave him the idea of writing a play with a person of color at the center of it, which became ‘Othello.’”

After finding inspiration from the influences around him, Shakespeare himself became both inspiration and solace for writers in the following centuries, such as Romantic poets from the 1700s to 1800s.

For so long, people have turned to Shakespeare in times of stress and need.

Bate’s latest book, “Bright Star, Green Light: The Beautiful and Damned Lives of John Keats and F. Scott Fitzgerald,” explores in part the life of Romantic poet John Keats. Keats battled tuberculosis, and during times of illness or loneliness, he turned to Shakespeare for comfort.

“Keats says that because of Shakespeare, he can never be lonely. I think that's one of the things great literature does for us,” Bate said. “If you talk to people suffering from depression, often they'll have this feeling they are totally alone. But you can discover through literature that others have been to the same place and have come through on the other side.”

Bate is interested in how the humanities, especially poetry, can be a tool for well-being. He and his wife founded a charity in the U.K. called the ReLit Foundation that is devoted to using Shakespeare and poetry to manage stress and anxiety. The charity has brought healing literature to many stressful environments, including psychiatric health units and hospices. One that stands out in Bate’s mind is when they worked in a U.K. prison for extreme offenders.

“We did workshops with them using Shakespeare, and we have to be aware that there are psychopaths and mass murderers in Shakespeare — Macbeth, Richard III, Othello,” he said. “Working with those prisoners through the trauma, the guilt, the sense of taking a wrong path and spending a lifetime regretting it was an extraordinarily powerful experience.”

The charity’s inspiration comes from Bate’s personal experience of poetry’s therapeutic power. Years ago, Bate and his wife found themselves in a hospital waiting room, unsure if their young daughter would make it through the night. Although she did recover, old magazines were the only reading material available to the parents in their hour of distress.

“When you think your 5-year-old daughter is dying, you don't really want to read about, ‘this or that Hollywood star introduces you to their beautiful home,’” Bate said.

Instead, a poem his wife found in her bag helped her through that evening. The couple later realized that others in similar situations might also find comfort in poetry.

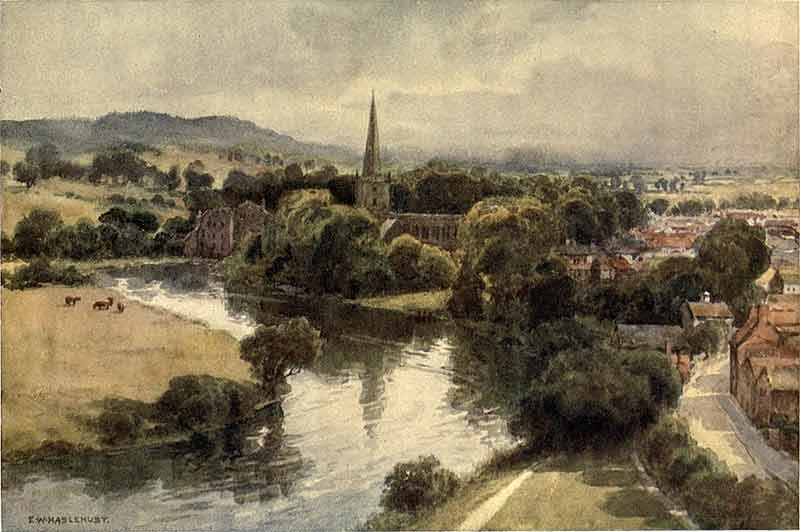

A series of outbreaks in London forced Shakespeare back to his hometown in the country, Stratford on Avon, where he had time to write more complex plays. Description: “Stratford-on-Avon from the Memorial Theatre” by Ernest Haslehust, 1920.

Looking now toward our own post-pandemic life, will it be as marked by creativity as the Renaissance that followed the Black Plague? Though it’s not that straightforward, Bate does note that, in a like manner, later outbreaks of the bubonic plague in London shaped Shakespeare’s development as an artist.

Epidemics often closed London’s theaters, forcing Shakespeare into the country. Early in his career, this time away from pressures helped him craft his trademark writing style. In later years, other outbreaks gave him freedom to write more complex plays that explore the darker sides of humanity.

Bate sees similar opportunity for soul-searching creativity to emerge from our time of solitude imposed by the COVID-19 pandemic.

“I think one thing that has come out of enforced lockdown is that it has given people time and space for deep thinking and wider reading, and for stepping back from your perspective to see the longer perspectives of history, cultural change, cultural diversity,” he said. “In our incredibly hurried, restless, modern world, the forced slowing down has been of value.”

More Arts, humanities and education

ASU professor, alum named Yamaha '40 Under 40' outstanding music educators

A music career conference that connects college students with such industry leaders as Timbaland. A K–12 program that incorporates technology into music so that students are using digital tools to…

ASU's Poitier Film School to host master classes, screening series with visionary filmmakers

Rodrigo Reyes, the acclaimed Mexican American filmmaker and Guggenheim Fellow whose 2022 documentary “Sansón and Me” won the Best Film Award at Sheffield DocFest, has built his career with films that…

Pen Project helps unlock writing talent for incarcerated writers

It’s a typical Monday afternoon and Lance Graham is on his way to the Arizona State Prison in Goodyear.It’s a familiar scene. Graham has been in prison before.“I feel comfortable in prison because of…