New discoveries from an ancient Homo erectus skull

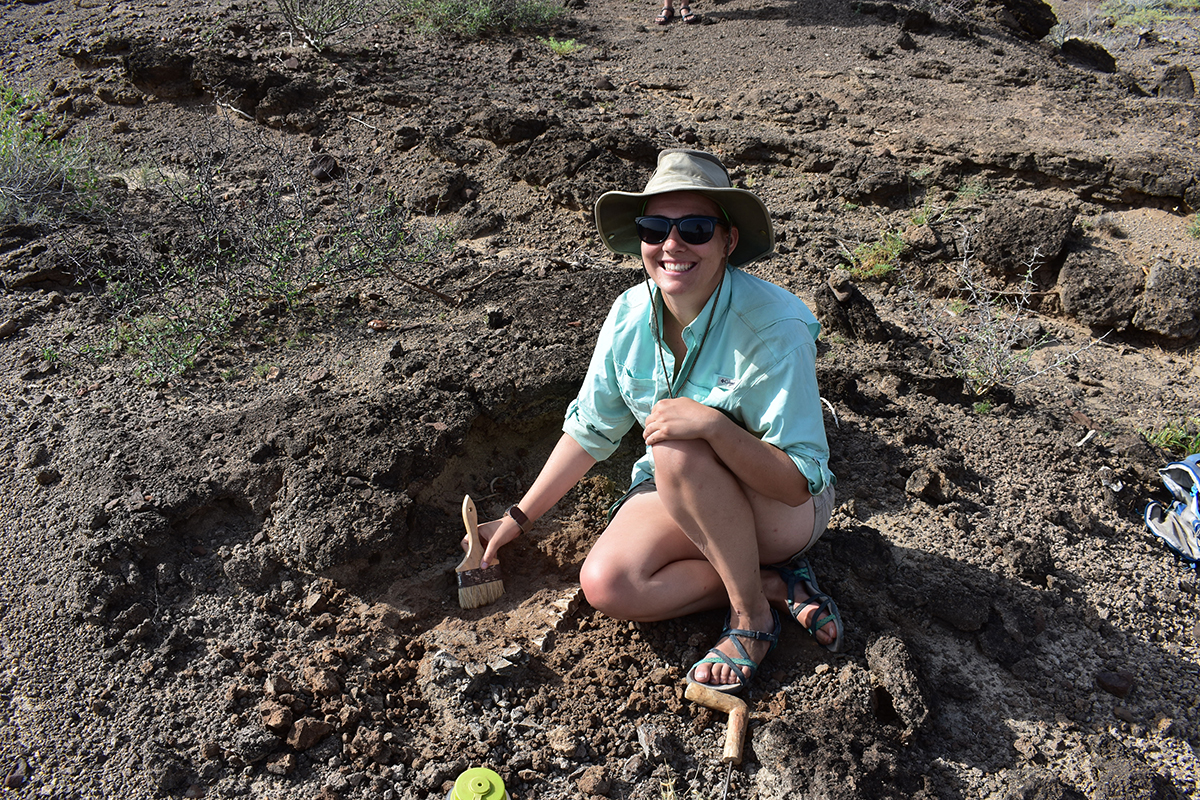

Students looking for fossils by "crawling" along the landscape, examining every rock and bone for the possibility of discovering another part of a Homo erectus fossil. Ashley Hammond image.

A new study by researchers, including Arizona State University graduate student Maryse Biernat, verifies the age of one of the oldest specimens of Homo erectus, the first ancient species with humanlike body build and behavior.

While retracing the location of the original fossil discovery made at East Turkana, Kenya, in the 1970s, the researchers found two new specimens at the site, the earliest skeletal pieces of H. erectus yet discovered. The results of the study, led by Ashley Hammond of the American Museum of Natural History’s Department of Anthropology, are published this week in the journal Nature Communications.

“Homo erectus is the first hominin that we know about that has a body plan more like our own and seemed to be on its way to being more humanlike,” Hammond said. “It had longer lower limbs than upper limbs, a torso shaped more like ours, a larger cranial capacity than earlier hominins, and is associated with an advanced tool industry — it’s a faster, smarter hominin than Australopithecus and earliest Homo.”

In 1974, scientists at the East Turkana site found the original fossil — a large chunk of the occipital bone at the back of the skull — and dated it to 1.9 million years old. But some paleoanthropologists argued that the specimen, while showing peculiar features of Homo erectus anatomy, could have come from a younger deposit and was possibly moved by erosion to the spot where it was found.

Confirming the age of the East Turkana fossil is key to identifying the probable source of early Homo erectus at the Dmanisi site in the Republic of Georgia, which dates to 1.78 million years ago — the earliest collection of hominin fossils outside of Africa.

The inside of a Homo erectus skull fragment from East Turkana, Kenya found in 1974. Ashley Hammond image.

To pinpoint the correct location, the researchers revisited the site, relying on archival materials and geological surveys. The research team sifted through hundreds of pages from old reports and published research, reassessing the initial evidence and searching for new clues. Satellite data and aerial imagery were reviewed to find out where the fossils were initially discovered so that they could recreate the location of the original site and place it in a larger context for determining the age of the fossils.

Within 50 meters of this original fossil’s location, the researchers found two new hominin specimens: a partial pelvis and a foot bone. Although the researchers say they could be from the same individual, there’s no way to prove that after they’ve been separated for so long.

“There’s no doubt that the anatomy of the original skull fragment implies that it should be assigned to Homo erectus,” said William Kimbel, ASU Institute of Human Origins director, who has studied the specimen but was not involved in the new study. “The team makes a strong case that the fossil is as old as the sediments on which it was found, making it among the oldest Homo erectus fossils in the world.”

The oldest fossil evidence for this species, dated at 2 million years old, was discovered in Drimolen, South Africa, where an international team, including ASU researcher Gary Schwartz, unearthed the earliest known skull of Homo erectus.

The scientists also collected fossilized teeth from other kinds of vertebrates, mostly mammals. From the dental enamel, they collected and analyzed dietary isotope data to paint a better picture of the environment in which early Homo erectus lived around early Pleistocene Lake Turkana.

Maryse Biernat in the field looking for fossils. Image courtesy Maryse Biernat.

“Our analysis shows that the environment included a lot of grazing herbivores that preferred to live in open environments like grasslands,” said team-member Biernat, a graduate student in the School of Human Evolution and Social Change and an affiliated student in the Institute of Human Origins. “That’s the type of environment we think could have stimulated the evolution of some of the familiar humanlike features we see in Homo erectus.”

The research is published as “New hominin remains and revised context from the earliest Homo erectus locality in East Turkana, Kenya,” Nature Communications, Ashley S. Hammond (American Museum of Natural History), Silindokuhle S. Mavuso (University of the Witwatersrand) Maryse Biernat (ASU), David R. Braun (The George Washington University and the Max Planck Institute for Evolutionary Anthropology), Zubair Jinnah (University of the Witwatersrand), Sharon Kuo (The Pennsylvania State University), Sahleselasie Melaku (National Museum of Ethiopia and Addis Ababa University), Sylvia N. Wemanya (National Museums of Kenya and the University of Nairobi), Emmanuel Ndiema (National Museums of Kenya), David B. Patterson from the University of North Georgia.

Written in collaboration with the American Museum of Natural History.

More Science and technology

ASU and Deca Technologies selected to lead $100M SHIELD USA project to strengthen U.S. semiconductor packaging capabilities

The National Institute of Standards and Technology — part of the U.S. Department of Commerce — announced today that it plans to…

From food crops to cancer clinics: Lessons in extermination resistance

Just as crop-devouring insects evolve to resist pesticides, cancer cells can increase their lethality by developing resistance to…

ASU professor wins NIH Director’s New Innovator Award for research linking gene function to brain structure

Life experiences alter us in many ways, including how we act and our mental and physical health. What we go through can even…