ASU director on the changing landscape of activism and protest in America

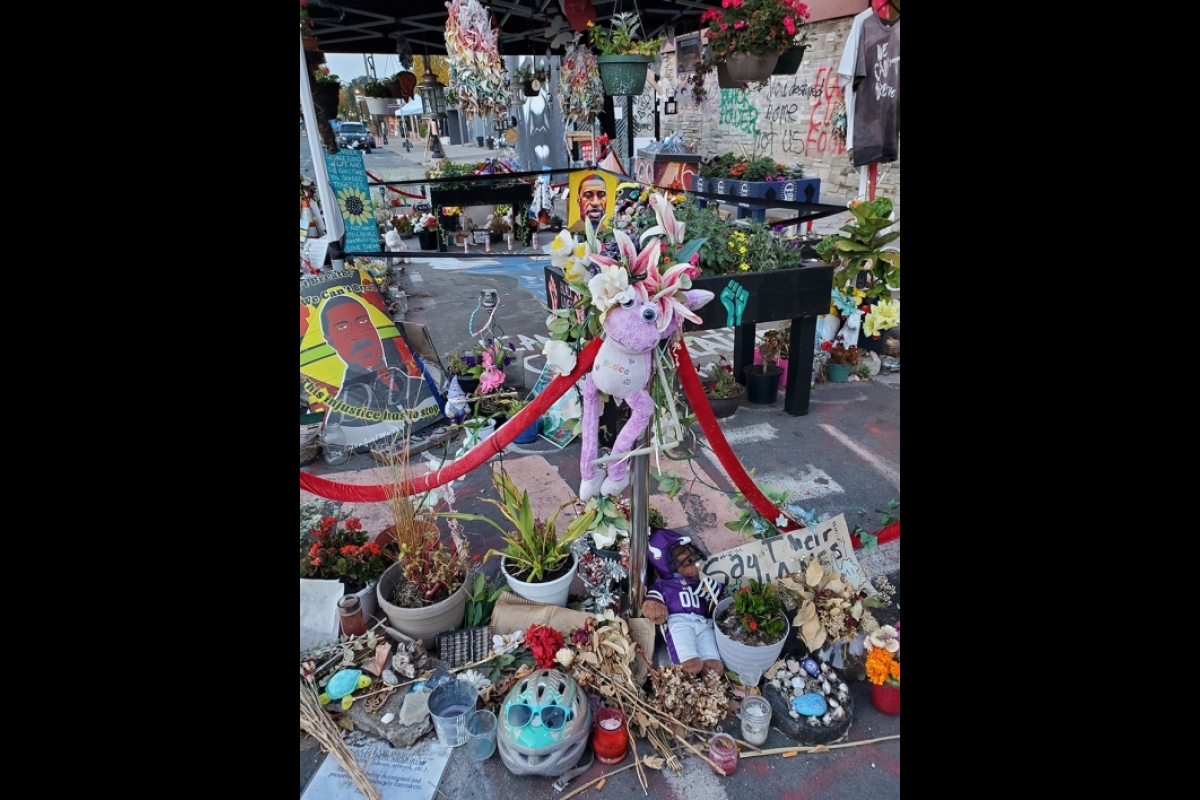

The George Floyd memorial in Minneapolis is shown on Oct. 10, 2020, with a mural by Peyton Scott Russell. The planters were built to sustain live plants left as offerings at the memorial. Photo courtesy of Michael McQuarrie

Last year, Michael McQuarrie was studying the street medics who supported the George Floyd protests that took place around the country. While heading back to Arizona from a trip to Michigan, he passed through Minneapolis to visit George Floyd Square, an “autonomous zoneA community that is autonomous from the generally recognized state or authority structure in which it is embedded — in particular, law enforcement. A tactic of protest used to hold space against state officials and develop alternative practices of organizing society.” and memorial site around the location where Floyd was killed.

“I wanted to show my daughter George Floyd Square and drop off a donation for their street medics. But in the course of doing that, it quickly became apparent that nobody was studying George Floyd Square,” McQuarrie said. “I felt that somebody should be studying that.”

So, from August 2020 until January 2021, McQuarrie visited George Floyd Square repeatedly with the goal of researching and understanding how an autonomous zone functions. Other autonomous zones popped up around the United States in 2020, namely in Seattle and New York City, but none had the staying power seen in Minneapolis. McQuarrie became interested in understanding what made George Floyd Square different, and why there was a lack of media attention on the place where a global protest movement originated.

This kind of work wasn’t totally new to McQuarrie — as the director of Arizona State University’s Center for Work and Democracy and an associate professor in the School of Social Transformation at The College of Liberal Arts and Sciences, he studies governance, urban politics and culture, community development, nonprofit organizations, the labor movement and other social movements. Much of his research focuses on the transformation of urban politics, governance and civil society — most particularly the relationship between geography and inequality, and politics and inequality.

Throughout his time at George Floyd Square, McQuarrie got to know the organizers, leaders and community members who are at the forefront of the movement. Developing these relationships led him to collaborate with the George Floyd Square community and Flowstate Films to produce an informational five-minute video that gives a look into the day-to-day of George Floyd Square.

“We wanted people to have a better understanding of George Floyd Square, and that's what the video is,” he said. “It was drafted in consultation with the community at 38th Street and Chicago Avenue. A lot of the footage is shot on people's phones, so it's literally a collaborative project with people there and who have been there. When you look at the video, you're looking through the eyes of people that are active participants.”

For McQuarrie, it was most important to him not to center himself and his research in this project, but instead give a truthful, firsthand account of what’s happening at George Floyd Square while focusing on what it says about contemporary urban protest.

“I think the principle that I went in with, which was different from how I've approached other research projects, is I went in there as a supporter of the square first and as a researcher second,” he said. “As a white man and a sociologist in a Black space of protest, it has been necessary to operate with that principle and I think that's guided my dialogue with the community.”

Since the video was released on March 31, it has been viewed, shared and liked about 30,000 times on Facebook and Instagram. Through the process of developing the video and observing George Floyd Square, McQuarrie said he believes a new kind of activism is emerging.

“We are in a moment when I think the traditional repertoires of protest — demonstrations in front of capitol buildings to get policy changed and implemented by applying pressure of public opinion to policy makers — are breaking down along with a lot of other institutions,” he said. “At the same time, we don't really have very many good ways of developing alternatives to traditional failed solutions to these problems. So I think the move toward things like occupations is going to be more and more prevalent as people try to imagine and develop alternatives.”

Aside from understanding George Floyd Square as a novel protest tactic, there are many other elements McQuarrie observed that make it particularly distinctive.

“George Floyd Square emerged in a neighborhood that has long-standing problems and is pressured by gentrification,” he said. “Building an effective protest in such a place requires people who can bridge different constituencies. In the square it has mostly been Black women who have the skills and networks to accomplish this. Unlike many autonomous zones, George Floyd Square is also a ‘sacred space’ for mourning along with being an ongoing site of protest.”

More Law, journalism and politics

Can elections results be counted quickly yet reliably?

Election results that are released as quickly as the public demands but are reliable enough to earn wide acceptance may not…

Spring break trip to Hawaiʻi provides insight into Indigenous law

A group of Arizona State University law students spent a week in Hawaiʻi for spring break. And while they did take in some of the…

LA journalists and officials gather to connect and salute fire coverage

Recognition of Los Angeles-area media coverage of the region’s January wildfires was the primary message as hundreds gathered at…