Editor's note: This story originally appeared in the spring 2021 issue of ASU Thrive magazine.

When Greg Asner looks out at the world from one of the countless locales he has visited — through his work mapping biodiversity, he has been all over, from the Brazilian Amazon to the Andes Mountains, Borneo to Madagascar, and beyond — he doesn’t just see the flora and fauna of a region. His unique way of looking at the world goes beyond the perspective he gets from the seat of a twin-propeller plane that soars over the tree canopy or by scuba diving on a coral reef.

“My brain works on evolutionary time,” said Asner, director of ASU’s Center for Global Discovery and Conservation Science. Even looking out onto the bay outside his window in Hawaii, he sees past its current form to its geological and biological history, to why this place is special.

The big picture is more than the reefs right under the water’s surface — it’s the history of Hawaii’s isolation and formation that helped bring about the thousands of species that live only in those reefs.

“I can kind of see it back in time and why it was unique, and I can do that anywhere on the planet,” he said.

It sounds a bit like magic, and in a way it is. But the real magic comes when Asner combines that worldview with Earth-mapping technology. Through that technology, satellite imaging and geospatial data can reveal ecosystems’ details as they exist today — all the animals and plants that live in a certain place. Combine that with Asner’s historical perspective, and he can explain why it’s so crucial to save that land. The technology reveals what species exist there now, and his evolutionary knowledge tells him why that came to be the only place they can exist.

“That’s how I, and the (Global Safety Net) team, view the planet’s surface,” he said.

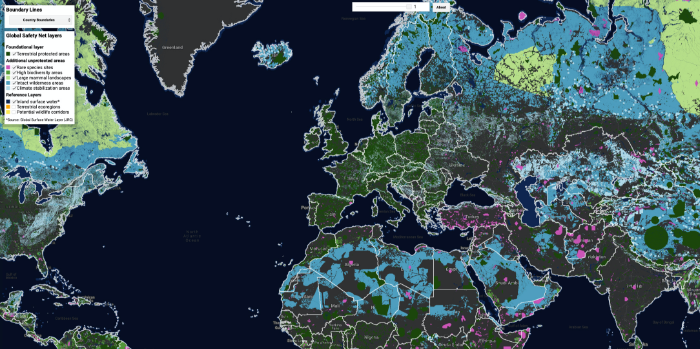

The GSN is the culmination of this work. It’s a blueprint for saving areas of Earth essential for biodiversity and climate resilience, and the first estimate of the total amount of land area requiring protection in order to address the dual crises of biodiversity loss and climate change.

With the ASU Global Institute of Sustainability and Innovation as a key player, the GSN finally answers a complicated question that accompanies any conservation work: Where, exactly, should we put our efforts to save the most species and mitigate the worst of climate change?

One Earth says that because of the Global Safety Net, 100 articles have been written, 40 maps have been requested and the overall narrative is changing that the environmental issues we currently face, though immense, are solvable.

Why biodiversity matters

In the last 50 years, we’ve lost more than two-thirds of the world’s wildlife populations on average, according to a recent World Wildlife Report. A United Nations report, co-authored by Leah Gerber, director of ASU’s Center for Biodiversity Outcomes, found that Earth’s biodiversity is declining at a rate unprecedented in human history. One million animal and plant species are now threatened with extinction.

That biodiversity loss has huge impacts on humans, no matter where we are. It makes pandemics, like COVID-19, more likely. And the way to prevent diseases from leaping from animals to humans, Gerber wrote in Issues in Science and Technology, “will have to lie with protecting and reporting wildlife habitat and conserving biodiversity.”

Biodiversity is linked to our health in other ways, too.

“The more (healthy and thriving) species that naturally occur in an area, the better that ecosystem is able to absorb shocks, threats and disturbances,” said Beth Polidoro, an associate professor of environmental chemistry at ASU, involved in the Center for Biodiversity Outcomes. “We need these healthy ecosystems because they provide ecosystem services for us.”

Healthy forests provide clean air; healthy soil is needed for us to grow food; healthy rivers maintain water quality.

The Arizona connection

And although biodiversity may conjure images of far-off places, it matters in our own backyards. The Sonoran Desert, covering 100,000 square miles across Arizona, California and Mexico, is the most biodiverse desert on the planet, home to more than 2,000 plant species, more than 350 bird species, 60 mammal species and up to 1,000 species of native bees.

Losing the plants whose roots protect the Colorado River could destabilize a fresh water system that supplies drinking water to 40 million people and nearly 6 million acres of farmland. The loss of bees means losing their pollination services for countless other species. Bulldozing wild land as urban sprawl expands can mean losing wildlife forever.

In Arizona alone, the GSN would set aside more than 66,000 square miles, or about 59% of all the state’s land, in order to preserve its biodiversity and ecosystems. Crucial areas also extend out west: In Utah, the blueprint would save nearly 59,000 square miles, or 69% of the land; in Nevada, more than 95,000 square miles, or 86% of the state’s land; and in California, some 82,000 square miles, half of the state’s land. The mountains, deserts and canyons that span these states are unique ecosystems and crucial habitats for thousands of species.

Working across departments

Even though Asner is based in Hawaii, he was inspired to come to ASU and start GDCS, he said, because of how the sustainability mandate through President Michael M. Crow isn’t hyperbole — it’s real.

“The university is trying to play a role beyond standard academia, forging and influencing communities up to U.N.-level decision-making,” he said.

The goal of GDCS is to understand what we have in terms of biodiversity, Asner explains, and work with decision-makers to find solutions to keep those things alive and healthy on the planet.

ASU’s sustainability efforts stretch beyond that center. Its work to protect critical biodiversity areas reaches across departments, like to the School of Mathematical and Statistical Sciences, where Steffen Eikenberry is a postdoctoral fellow. Eikenberry uses math to quantify environmental problems like consumption and land use.

“The climate crisis and biodiversity crisis are twin crises fundamentally driven by consumption throughout the world, primarily the rich world,” he said. But how do you quantify that, and how do you find out the most important things to change in order to solve those crises? “If you want to say anything, you have to do the math.”

Cross-departmental work for an issue as big as biodiversity is important because of the unique expertise everyone brings to the table.

Angela Amanakwa Kaxuyana, part of the senior leadership of the Brazilian Coordination of Indigenous peoples in the Amazon, and her team are using the Global Safety Net in the real world to help protect her people’s land in the Amazon rainforest. With 80% of the global biodiversity managed or owned by Indigenous people, Kaxuyana says that scientists and native communities have long held the same goal of wanting to protect the planet. The GSN has provided campaigners and grassroots organizations the key information they need to take action to stop development projects and promote land conservation.

The importance of Indigenous knowledge

More than one-third of the lands identified as biodiversity hot spots in the GSN are communally held by Indigenous peoples, and ASU itself sits on ancestral territories, including the Akimel O’odham (Pima) and Pee Posh (Maricopa) Indian communities. Acknowledging Indigenous peoples is built into ASU’s work as an institution, into Asner’s work as a scientist and into ASU’s audacious goals to protect biodiversity and mitigate climate change.

“We start with the fundamental premise that there have been caretakers of this land long before we showed up in 1885,” said Bryan McKinley Jones Brayboy, director of the Center for Indian Education. One objective of ASU as an institution is to “leverage our place,” and that means considering and working with tribal nations.

While other institutions and researchers may go on to Indigenous lands and tell Indigenous peoples what they need to do, at ASU, the goal is for Indigenous peoples to be an active part of that effort from the start. That’s especially true when it comes to biodiversity work.

Indigenous peoples account for 6% of the global population, yet manage 80% of the world’s remaining biodiversity.

One important approach Asner and ASU take to this work, according to Brayboy, is to consider why so much of the pristine lands are being managed by Indigenous peoples, and what that says about their relationship with these lands.

“You don’t just need the principles of how people are stewarding and guarding the lands,” Brayboy said, “but you actually need the people themselves.”

Assistant Professor Haunani Kane will soon live that firsthand when she comes to ASU this summer, where she’ll combine her experiences as a Native Hawaiian with Western geospatial technology for the GSN. One example is the way she considers coral, not only as something that grows in the ocean but as something essential to her people.

“We are looking at these organisms, and the places that we study as a part of ourselves. We believe that we are nothing without our land or without our resources, so that’s really what drives the work that we do,” Kane said. “In terms of climate change, we’re studying the impacts and the changes out of necessity. It’s something that we are trying to understand because our survival and our way of life will depend upon it.”

The Global Safety Net, a global blueprint for a livable planet, uses a first layer for already protected areas such as national parks and wildlife sanctuaries. Second are rare-species sites that need to be protected immediately. High-biodiversity areas are third. Regions with large mammals, continuous intact wilderness and climate stabilization areas complete the mapping. Together, they total 50.4% of the planet.

What’s next?

Human activity has pushed us past the point of saving all of nature, but the GSN lays out the path and the map for saving half of Earth’s land (50.4%, to be exact). Any lower and we destabilize those ecosystem services, Asner said, like clean water, pollination, self-regulating forests that don’t require human intervention to keep trees free of pests, and carbon sinks that naturally keep our world from getting too hot. Any higher, and those essentials for living healthy lives on the planet are nearly impossible to achieve.

It will be a feat.

The GSN is a group effort from ASU, the University of Minnesota, the research organization Resolve and the nongovernmental organization Globaïa. It’s funded by the nonprofit One Earth, and other funding has supported Asner’s aircraft program that did the foundational biodiversity mapping, including the MacArthur Foundation, the film director James Cameron, and media heir William Hearst III. The Leonardo DiCaprio Foundation has also been a big supporter of Asner’s work.

“We only get one planet,” DiCaprio said at the 2014 United Nations Climate Summit. “Protecting our future on this planet depends on the conscious evolution of our species.” Though he was speaking generally, that sentiment explains why DiCaprio supports One Earth and its work like the GSN: We only have one Earth, and this is a way to save it.

Those big names help researchers like Asner try out new approaches to biodiversity work, whereas governments tend to be more risk-averse. But governments still need to collaborate and establish action plans to preserve these lands.

“What we’re doing is ultimately not the answer,” Asner said. “It’s the pathway for those who want to answer the question of ‘What do we do?’”

The GSN is a toolkit that decision-makers need to carry out, but getting conservation policy passed can be a challenge. Polidoro has one suggestion: Get scientists involved with writing legislation.

“People that create policies don’t always have access to the scientific literature,” she said. “Find a governmental liaison, a lobbying organization or policy organization that you can connect with and help them draft legislation. ... You can’t work in isolation.”

Asner’s unique way of looking at the world unfortunately doesn’t let him glimpse into the future to see if decision-makers will adopt the GSN. But he’s still sure it will have an impact. The data is publicly available through the GSN site, which has an interactive viewer to let users explore findings by country, ecoregion and all 50 U.S. states.

“The most powerful thing about the GSN is it serves to teach everyone on the planet what we’ve got,” Asner said.

And what we need to protect.

Explore Earth’s biodiversity hot spots by video: Get a new perspective on Earth at globalsafetynet.app.

Want to contribute to help save these biodiversity hot spots? Donate through the ASU Foundation and specify it’s for GDCS at asufoundation.org.

Watch the student documentary “Holding on to the Corn,” which shares an intimate look at the Hopi relationship with the Earth at sustainability.asu.edu/media/student-videos/holding-on-to-the-corn.

Learn more about Hopi Tutskwa Permaculture Institute, a community nonprofit based in the village of Kykotsmovi, located in northern Arizona on the Hopi Reservation, at hopitutskwa.org.

Story by Kristin Toussaint, the assistant editor of the Impact section at Fast Company. She was previously a senior news reporter at Metro in New York City. All photos courtesy Greg Asner.

Top photo: ASU’s Greg Asner is involved in many projects, from the Global Safety Net that maps biodiversity hotspots, to the Allen Coral Atlas, which maps and monitors coral reefs to help provide data for bringing reefs back to health. He made this image in Micronesia.

More Science and technology

Indigenous geneticists build unprecedented research community at ASU

When Krystal Tsosie (Diné) was an undergraduate at Arizona State University, there were no Indigenous faculty she could look to in any science department. In 2022, after getting her PhD in genomics…

Pioneering professor of cultural evolution pens essays for leading academic journals

When Robert Boyd wrote his 1985 book “Culture and the Evolutionary Process,” cultural evolution was not considered a true scientific topic. But over the past half-century, human culture and cultural…

Lucy's lasting legacy: Donald Johanson reflects on the discovery of a lifetime

Fifty years ago, in the dusty hills of Hadar, Ethiopia, a young paleoanthropologist, Donald Johanson, discovered what would become one of the most famous fossil skeletons of our lifetime — the 3.2…