Editor's note: This story originally appeared in the spring 2021 issue of ASU Thrive magazine.

This story is also featured in the 2021 year in review.

Sunny. Sprawling. Rugged. Many words come to mind to describe the Phoenix metropolitan area. “Fragile” often isn’t one of them.

But a decade ago, the Valley was the poster child for an easily upended economy. Between 2000 and 2007, the area’s economy boomed. Housing prices doubled. Unemployment dropped to 3.1%. Then the real estate bubble burst, seriously damaging the state’s economy.

“The Great Recession showed us that the gravy train that existed then was an unhealthy, unsustainable growth model,” said Chris Camacho, president and CEO of the Greater Phoenix Economic Council.

ASU has been at the forefront of creating a very different model for the Valley — one that isn’t just resilient in the face of change, but “antifragile.”

According to economist Nassim Nicholas Taleb, the opposite of fragile is something that thrives in response to shocks and disorder. Examples include parts of Colorado and Washington state where amid the turmoil of the COVID-19 pandemic, some communities continue to flourish.

An antifragile economy doesn’t just benefit people at the top. The focus on all levels of the economy can mean more educational opportunities, higher wages and more stability for everyone.

“We bring together a variety of different companies and other kinds of entities to work with each other. It’s not random — the intention is to create a community that is greater than the sum of its parts.”

— Neal Woodbury, chief science and technology officer at ASU

But what does it take to create an antifragile economy?

For starters, an educational system that serves people of all backgrounds and ages, from preschool through continuing education. A workforce that, as a result, is technically skilled, adaptable and creative — not to mention homegrown. An antifragile economy can’t rely on importing brainpower while locals settle for lower-wage jobs.

Diversity is key — in all forms, from ideas to the student population to industries.

“It’s not antifragile if you have a small number of people with the wealth and power and a large number of people with very little,” said Neal Woodbury, chief science and technology officer at ASU. “There has to be a mechanism by which a diversity of thought can come to the forefront. Otherwise, you don’t have that breadth of capability to rise to the occasion.”

Eric Yuan, Zoom’s CEO, credited a “well-educated, skilled and diverse talent pool” and ASU’s engineering program when the company announced last year that it would open an R&D center in Phoenix.

But an antifragile economy doesn’t depend on attracting existing companies — it generates its own, giving birth to entirely new fields by providing antifragile skills.

One example is the Ira A. Fulton Schools of Engineering’s new master’s degree in modern energy production and sustainable use developed to help students from other fields get skilled in engineering-related industries.

That’s what brought graduate student Martin Flores to the program.

“I look forward to a well-rounded experience that will allow me to choose from among many different directions,” Flores said.

This is all part of the approach that ASU is taking: championing entrepreneurship and risk-taking, as well as educational inclusion, to reinvent the Valley’s economy, on multiple fronts.

Inclusive education

The COVID-19 pandemic highlighted how different life can be for people with — and without — college degrees.

Last April, as restaurants, stores and other businesses shrank or shuttered, the U.S. unemployment rate shot up to 14.7%. But people who didn’t graduate from college were more than twice as likely to lose their jobs than workers with a college degree. By September, when businesses were rehiring, just 4% of college-educated people were still jobless, compared with 8% of high school-educated workers.

Lack of education doesn’t just impact individuals and families, but entire communities. Companies gravitate to places with plenty of skilled workers; those jobs help create other jobs. More knowledge means more potential for startups.

“As you produce people, you produce ideas, which turn into companies,” Camacho said. “Those turn into job catalysts, which turn into revenue for our state and our county.”

Arizona lags behind — 20% of high school freshmen in the state finish college, compared with 40% across the U.S. Unlike the many colleges that take pride in their exclusivity, part of ASU’s mission is to make higher education accessible.

On the K–12 front, the university has partnered with local school districts to ensure that kids are ready for the challenges of college and to boost college-going rates. Examples are an outreach program to encourage first-generation students to attend college and a program that helps foster kids succeed at the university. Community college partnerships let students attending two-year schools easily transfer to ASU and take classes in their home community.

ASU’s efforts aren’t just about volume, but diversity. The Hispanic community is the fastest-growing in Arizona, yet lags behind in college attendance.

“That’s probably the most economic potential to be unlocked,” Camacho said.

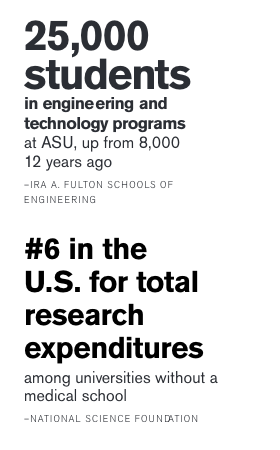

Overall, Hispanic enrollment at ASU has doubled over the past 12 years, and diversity has increased dramatically at the Fulton Schools. A centerpiece of the university, the engineering program has expanded from about 8,000 to 25,000 students in the last decade.

Kyle Squires, dean of the engineering schools, says that the percentage of Hispanic students is higher than national averages. That’s not enough: “We want to become the go-to destination for Hispanic students,” he said. “Their premier choice.”

ASU also has been a leader in serving nontraditional students who can be left out of higher education. In engineering, more than 30 online programs, including undergraduate and graduate degrees, are available.

A culture of entrepreneurship

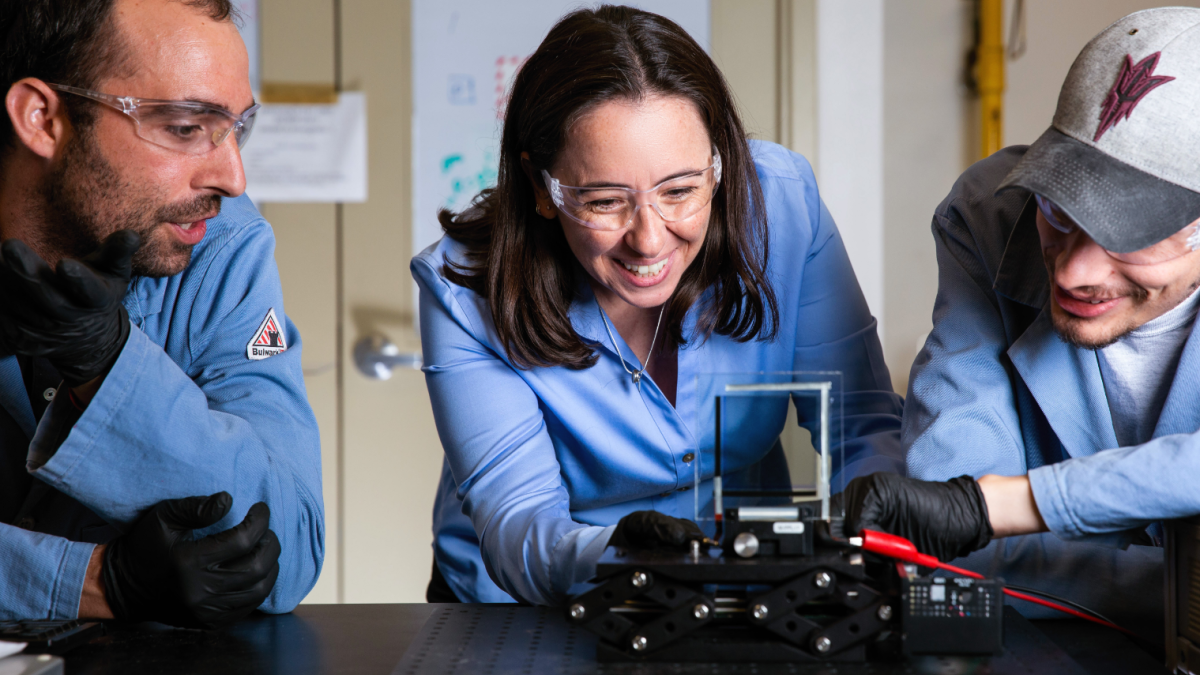

Mariana Bertoni, an expert in multiple engineering fields and an associate professor in the School of Electrical, Computer and Energy Engineering, credits a monthlong training program at ASU for helping her develop her ideas into a viable business. That program, the National Science Foundation’s Innovation Corps Site, is an entrepreneurship boot camp for researchers. It’s just one of many ASU initiatives designed to ensure that smart ideas don’t die on whiteboards or inside labs.

Bertoni’s company, Crystal Sonic, uses sound waves to cut the expensive crystal wafers that microchips are built on, preventing waste and saving money. With assistance from a $200,000 fellowship from the Fulton Schools and participation in Venture Devils, she has raised $2 million in seed capital to pay for dedicated space and hire staff.

The J. Orin Edson Entrepreneurship + Innovation Institute, which administers the NSF I-Corps, has created many programs like Venture Devils and provides fellowships, workshops, mentorships, a makerspace and venture capital. It supports more than 700 entrepreneur teams and has raised more than $34.4 million in external funding for ASU’s entrepreneurial programs.

Fostering a risk-taking entrepreneurial culture is as crucial to establishing an antifragile economy as running a robust engineering program and educating future technologists, Squires said.

“We want to drive that with talent, and ideas that translate from the lab out into the community,” Squires said. “Tech companies are probably the core of future economic expansion, company formation and supporting the nontech sector in some cases.”

Early support from ASU can lay the foundation for outside grants and investments. Swift Coat, which specializes in spraying nanoparticle coatings onto surfaces to protect them from dirt, sun and other hazards, was born out of the Fulton Schools. Since then it has raised $180,000 in business plan competitions and $1 million from the U.S. Department of Energy’s Solar Energy Technologies Office, among other funds.

Entrepreneurship is such a cornerstone of an antifragile economy that ASU continually reinforces it, including with a new Master of Science in innovation and venture development degree, a transdisciplinary partnership among the Fulton Schools, the W. P. Carey School of Business and the Herberger Institute for Design and the Arts. The program is led by Cheryl Heller, a business strategist and design world icon.

Serial entrepreneur and industrial designer Travis Andren (’10 BS in industrial design) has come back to Arizona for the program to learn “what I don’t know” to help him build better businesses.

“My experience and time in industry was fruitful, but I wanted to do things that had a more positive impact,” Andren said.

OncoMyx Therapeutics is developing oncolytic immunotherapies to treat cancer, based on the work of Grant McFadden, director of the Biodesign Center for Immunotherapy, Vaccines and Virotherapy, and a professor in the School of Life Sciences at ASU. McFadden’s team has designed an oncolytic virus to specifically kill cancer cells without harming normal cells.

Innovating with industry

Cities around the country have been trying to breathe new life into their economies by better utilizing local universities, observes Douglas Holtz-Eakin, president of the American Action Forum, a center-right advocacy group based in Washington, D.C. The strategy gets mixed grades, Holtz-Eakin says, in part because typically universities don’t listen well, especially to the business community.

But at ASU, collaborating with outside stakeholders — big companies, startups, small businesses, Native American tribes, schools and nonprofits — is part of the ethos. These partnerships are vital not only to building an antifragile economy, but to fulfilling ASU’s educational mission.

“We want our industry partners engaged with our students before they even start their first year of engineering school,” Squires said. “We refer to it as the ’Fulton difference.’”

The university has developed or is working on seven innovation corridors, facilities that bring together students, faculty, startups, established companies and support infrastructure. The Arizona Health Solutions Corridor expands on the university’s partnership with Mayo Clinic. ASU Research Park focuses on wearable technology, flexible displays and other cutting-edge technologies. The others also provide interdisciplinary resources to accelerate innovation in other industries.

Stanislau Herasimenka, an assistant research professor in electrical engineering, launched his startup out of the Quantum Energy and Sustainable Solar Technologies (QESST) Engineering Research Center. He and his partner in Regher Solar are developing solar cells for satellites — the super-thin cells are cheaper to make than traditional cells, and more resistant to space’s radiation damage. He was able to leverage an ecosystem of resources at QESST. Herasimenka and three ASU faculty members recently received a $1.8 million award from the U.S. Department of Energy to develop a facility that will let academics work with industry partners to test solar ideas.

ASU startup Regher Solar’s flexible solar cells for satellites are cheaper and faster to make than traditional cells (shown here) and more resistant to damage in space. Launched by Stanislau Herasimenka, a researcher in electrical engineering, the company received $0.5 million of SBIR funding from NASA, DOD and NSF to develop affordable and scalable solar technology for space.

Skysong Innovations helps bring technologies developed at ASU to market, supporting tech transfer, licensing, startup launch and major investments.

SkySong, the ASU Scottsdale Innovation Center, has generated more than $130 million in state tax revenues and launched 160-plus startups, said Woodbury. It is expected to provide an economic impact to Arizona of nearly $58.2 billion over the next 30 years.

“We bring together a variety of different companies and other kinds of entities to work with each other,” Woodbury said. “It’s not random — the intention is to create a community that is greater than the sum of its parts.”

One recent success is OncoMyx Therapeutics, which creates virus-based cancer treatments. The company raised $25 million in 2019 and spun off from ASU last year.

Partnering with industry is a win-win for everyone, including mature companies, which benefit from a direct pipeline to research and to coveted engineering graduates.

“From a company perspective, it’s competitive,” Squires said. Engineering undergraduates are often hired before they’ve started their senior year.

Preparing for the future

Amid the good news, challenges remain. Arizona’s economy remains stubbornly fragile, with too much income disparity and declining GDP. The state has recovered only two-thirds of pandemic job losses.

The coming years will be crucial, says the Greater Phoenix Economic Council's Camacho.

The Valley needs to take advantage of the current situation to drive investment and policy decisions, so the economy emerges more dynamic and competitive, or it will be left behind, he said.

“The next decade sets the trajectory for the next 50 years.”

Learn more about ASU’s impact on the Arizona economy at impactarizona.asu.edu.

Story by Sara Clemence. A reporter and writer, Sara Clemence is a former travel editor for The Wall Street Journal, news director for Travel + Leisure, deputy business editor for the New York Post, and lifestyle editor for Condé Nast Portfolio and Forbes.com. She is also author of “Away & Aware: A Field Guide to Mindful Travel.”

Top photo: Mariana Bertoni leads the lab DEfECT (Defect Engineering for Energy Conversion Technologies) focusing on how defects can affect electrical and optical properties of material. She also is chief technical officer at Crystal Sonic, an ASU startup that uses a process she invented in which sound waves are used to cut the expensive crystal wafers that microchips are built on, preventing waste and saving money. Photo by Deanna Dent/ASU

More Science and technology

Hack like you 'meme' it

What do pepperoni pizza, cat memes and an online dojo have in common?It turns out, these are all essential elements of a great cybersecurity hacking competition.And experts at Arizona State…

ASU professor breeds new tomato variety, the 'Desert Dew'

In an era defined by climate volatility and resource scarcity, researchers are developing crops that can survive — and thrive — under pressure.One such innovation is the newly released tomato variety…

Science meets play: ASU researcher makes developmental science hands-on for families

On a Friday morning at the Edna Vihel Arts Center in Tempe, toddlers dip paint brushes into bright colors, decorating paper fish. Nearby, children chase bubbles and move to music, while…