ASU film students to see their own possibilities in legacy of Poitier

When Arizona State University’s film school was named after the legendary actor Sidney Poitier last month, it represented not only a commitment to diversity and inclusion, but also a duty to Poitier’s extraordinary impact.

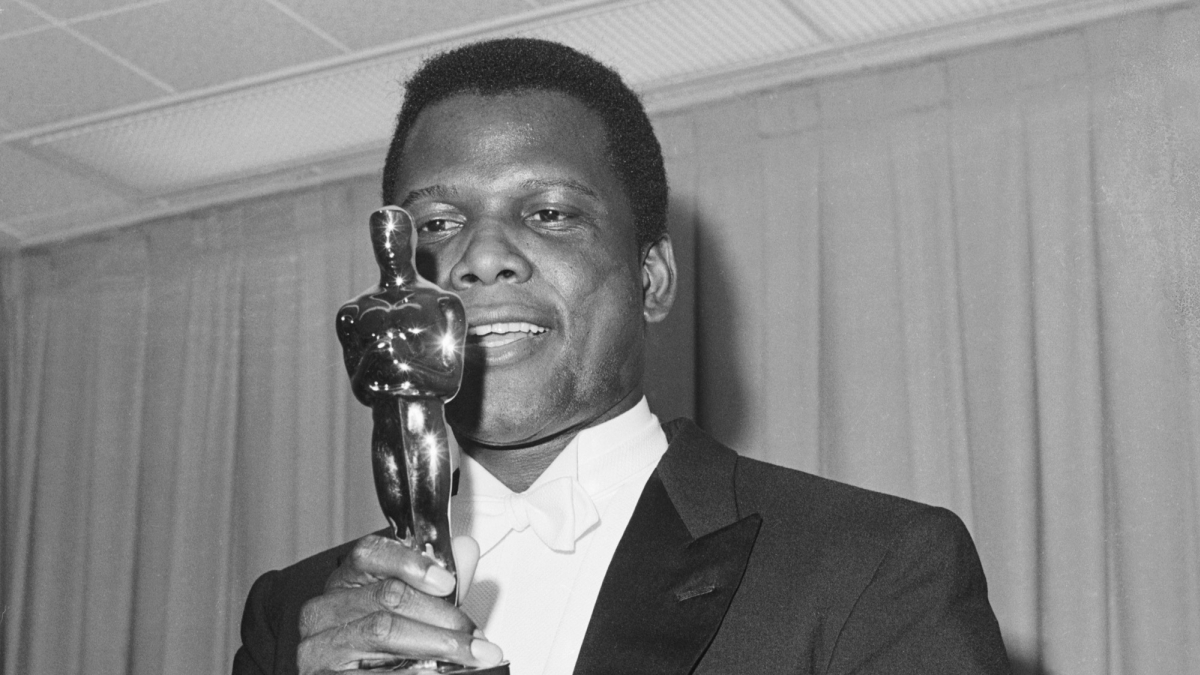

The Sidney Poitier New American Film School was named on Jan. 25 after the first Black man to win a best actor Academy Award, for “Lilies of the Field,” in 1964. Poitier turned 94 years old on Feb. 20.

Attending a film school named for Poitier will connect ASU’s students to the continuum of history, according to Tiffany Ana López, the new vice provost for inclusion and community engagement at ASU. She is the former director of the School of Film, Dance and Theatre in the Herberger Institute for Design and the Arts.

“He is an essential part of understanding American film history,” she said.

“He has a litany of ‘firsts,’ but it’s important for students and people following the film school to understand the impact of being first and to have people understand what is possible,” López said.

“This is why representation, seeing people who look like you on the screen, is so important. Because if you can’t see it, it’s hard to imagine being it.”

Jason Scott, interim director of the film school, said: “From the beginning, when we became aware that this naming would really happen, there was a public face that is glorious, but there is also the responsibility and ownership of that legacy.”

Part of that is teaching students about Poitier. In the fall, Scott and Lopez will teach a new class called “The Filmmaker's Voice,” which will focus on Poitier.

Students will not only see his film work, but also delve into interviews and other media. Over the semester, they’ll collect as many resources as possible into a digital repository to be kept at the school.

“Part of this is to get the current group of students to know who this person is and to help bring the stories to life,” Scott said.

“It will be, ‘You tell us how you connect to his story and how you’re inspired by him.’"

At the end of the semester, students will propose a video project based on the legacy of Poitier’s work. In the spring semester, the students will produce the projects.

“It could be a short bio, or a three-minute animated rendering of the story he tells about getting his first acting job,” Scott said.

Those short works could be displayed in the film school’s new location in downtown Mesa, which is expected to open in 2022.

'We had done it'

López said she wants students to understand how Poitier created opportunities for himself.

President Barack Obama awarded Sidney Poitier the Presidential Medal of Freedom in 2009. Photo courtesy Wikimedia Commons

Poitier grew up in the Bahamas and moved to New York as a teenager. Working as a dishwasher, he responded to an ad seeking actors for the American Negro Theatre.

In his 1980 memoir “This Life,” Poitier describes how, after a brief audition, he was rejected because of his strong Bahamian accent. So he bought a radio and listened to it constantly, mimicking the voices until he lost his accent. Six months later, he tried out again and was accepted. He later found out that he got in because not enough men had auditioned.

Soon, he won his first role, a small part in “Lysistrata” on Broadway. On opening night, he had such acute stage fright that he froze, bungling the lines. The audience laughed and the newspaper review the next day praised his comedic talents.

After acting in road shows for a few years, Poitier went to Hollywood in 1950 to star in his first movie, “No Way Out,” directed by Joseph Mankiewicz. He was 22 years old, playing a doctor who treats two white brothers who are racists, and he marveled at his at ease in front of the cameras.

By 1958, he had starring roles. In “The Defiant Ones,” Poitier and Tony Curtis played escaped prisoners who were shackled together. Curtis requested that both of their names appear above the credits. Both were nominated for best actor Oscars, with Poitier becoming the first Black man nominated. David Niven won that year for “Separate Tables.”

Poitier made a triumphant return to Broadway in 1959 in “Raisin in the Sun,” a play by Black playwright Lorraine Hansberry that he called “an uplifting experience.” He starred in the film version as well.

In 1963, Poitier traveled to southern Arizona to make “Lilies of the Field,” playing a handyman who reluctantly builds a chapel for a group of nuns. In “This Life,” Poitier says little about his time in Arizona except that the movie was on such a tight budget the shooting schedule was condensed into a fast two weeks.

Poitier won the best acting Oscar for his role. In his memoir, he recounted his reaction: “I was happy for me, but I was also happy for the ‘folks.’ We had done it. We Black people had done it. We were capable. We forget sometimes, having to persevere against unspeakable odds, that we are capable of infinitely more than the culture is yet willing to credit to our account.”

Poitier’s blockbuster year was 1967, in which three of his biggest hits were released: “To Sir With Love,” in which he plays an engineer teaching a rowdy group of students in London’s East End; “In the Heat of the Night,” playing a police detective investigating the murder of a white businessman, and “Guess Who’s Coming to Dinner,” in which Poitier’s character is engaged to a white woman. All of the movies directly addressed racial issues.

“It’s not just that he was the first one who did things, but that most of the things he did are relevant to our discussions of how we understand race and power, and race and status,” Scott said.

“His characters are complex, they’re not just Black savior heroes.”

Lois Brown, director of the Center for the Study of Race in Democracy at ASU, said that she was very moved by the naming of the film school for Poitier because his work helps people understand the challenges of being a person of color in America.

“He’s a person who used film to bear witness to the dignified and courageous ways in which people of color negotiated bias and racism and assumptions and stereotypes,” she said.

Brown, whose parents were teachers, first came to know of Poitier through books that were adapted to film, such as “To Sir with Love.”

“That also underscores the power of the film school. It’s such a multidimensional initiative because films are forever connected to narrative, and narrative can be made manifest in a number of genres,” said Brown, Foundation Professor of English at ASU.

Scott is compiling a spreadsheet of Poitier’s roles and the availability of his movies, and said that the actor played many captivating parts in lesser-known films. “Pressure Point” is a particularly relevant movie, in which Poitier plays a psychiatrist who must treat a Nazi sympathizer who tries to overthrow the country.

“It’s been fascinating to chart these less-remembered roles, and I’m excited for our students to see them for the first time, and not have this just be ‘Sidney Poitier’s Greatest Hits,'” Scott said.

On to directing

In “This Life,” Poitier wrote about his career slowdown in the 1970s, and the backlash over his many distinguished characters — often the only Black character in a movie filled with white people: “A Black man was put in a suit with a tie, given a briefcase; he could become a doctor, a lawyer, or police detective. That was a plus factor for us, to be sure, but it certainly was not enough to satisfy the yearnings of an entire people. It simply wasn’t.”

He stayed away from Hollywood during the heyday of Black exploitation films (mostly made by white men), which he saw as only temporarily satisfying to Black audiences, who would eventually want movies that reflected their lives better than a doctor or a hustler.

That’s where he saw the role of comedy. In “This Life,” he described screening “Uptown Saturday Night,” the third movie he directed, to a roomful of white production company executives in 1974. After the movie ended, there was an awkward silence from the group, who didn’t know what to make of its joyful depiction of Black humor and camaraderie. It was a huge hit.

“He was really elevating and normalizing Black culture through comedy, not through social justice movies, which he continued to act in but most of the stuff he directed was comedy,” Scott said.

Poitier returned to Arizona twice as a director. When he was directing “Stir Crazy” in 1980, Columbia Pictures wanted to rent what was then called the Arizona State Prison in Florence. The warden agreed and used the money to build a rodeo arena. More than 300 inmates signed on to be extras in the movie. Two years later, Poitier returned to Tucson to direct “Hanky Panky.”

Poitier acted in fewer films in the 1980s and '90s, adding roles in TV movies and shows, including portrayals of Thurgood Marshall and Nelson Mandela.

An inner compass

Poitier’s intentionality in choosing his roles and his career path is a key lesson for students, López said.

“He redefined roles in the film industry and on stage and for African Americans by rejecting parts that were based on racial stereotypes,” she said.

Until recently, students in the film industry were advised to say yes to every role or opportunity, she said.

“For our women, but also students from other groups, saying yes to everything is not only not safe, it could be damaging to your own sense of the impact you want to make in the world,” López said.

“And Poitier understood that. He was a model for that. You have to have your inner compass forge your career with a sense of the impact you want to have.”

The film school is deep in planning the many ways that Poitier’s legacy will be incorporated in teaching and scholarship. His work will serve as a starting point for students to explore 20th-century Black excellence.

“There’s Cicely Tyson, Harry Belafonte, Muhammad Ali, Hank Aaron,” Scott said.

“We can go beyond Poitier to the culture he was a part of.”

Brown said that Poitier’s roles showed the breadth and depth of experiences of people of color in the face of racism.

“I think because Sidney Poitier is such a giant in the field and because he is forever associated with gentility, graciousness and presence, he models for young people today how to hold your ground in the face of obstacles and challenges and downright exclusions. And sometimes hate,” she said.

“He confirms for them that we have already been there and there’s somebody who was out ahead of them and who has made a way to step into the field and create new paths.”

Brown said the renaming is a profound action.

“I can’t say enough how moving and institutionally powerful this is because it reminds us just how long the road is toward full inclusion and robust critical engagement with history and culture and the future,” she said.

Top image by Getty Images

More Arts, humanities and education

ASU’s Humanities Institute announces 2024 book award winner

Arizona State University’s Humanities Institute (HI) has announced “The Long Land War: The Global Struggle for Occupancy Rights” (Yale University Press, 2022) by Jo Guldi as the 2024…

Retired admiral who spent decades in public service pursuing a degree in social work at ASU

Editor’s note: This story is part of coverage of ASU’s annual Salute to Service.Cari Thomas wore the uniform of the U.S. Coast Guard for 36 years, protecting and saving lives, serving on ships and…

Finding strength in tradition

Growing up in urban environments presents unique struggles for American Indian families. In these crowded and hectic spaces, cultural traditions can feel distant, and long-held community ties may be…