Post-moratorium evictions surge expected to compound health, housing crises

Photo by BackyardProduction on iStock

As Maricopa County braces itself for the wave of evictions expected to follow an ever-changing moratorium deadline, researchers at Arizona State University's Knowledge Exchange for Resilience (KER) are working to predict the scale of this surge and to locate those most vulnerable.

“The concern is that once the eviction moratorium ends, you’re going to see all of the evictions that would have taken place from the beginning of the moratorium to the end of the moratorium suddenly being filed all at once,” said Lora Phillips, a sociologist for KER.

About 42% of people surveyed in the Phoenix metro area foresee being evicted or foreclosed on in the next two months, according to the Census Bureau’s Household Pulse Survey.

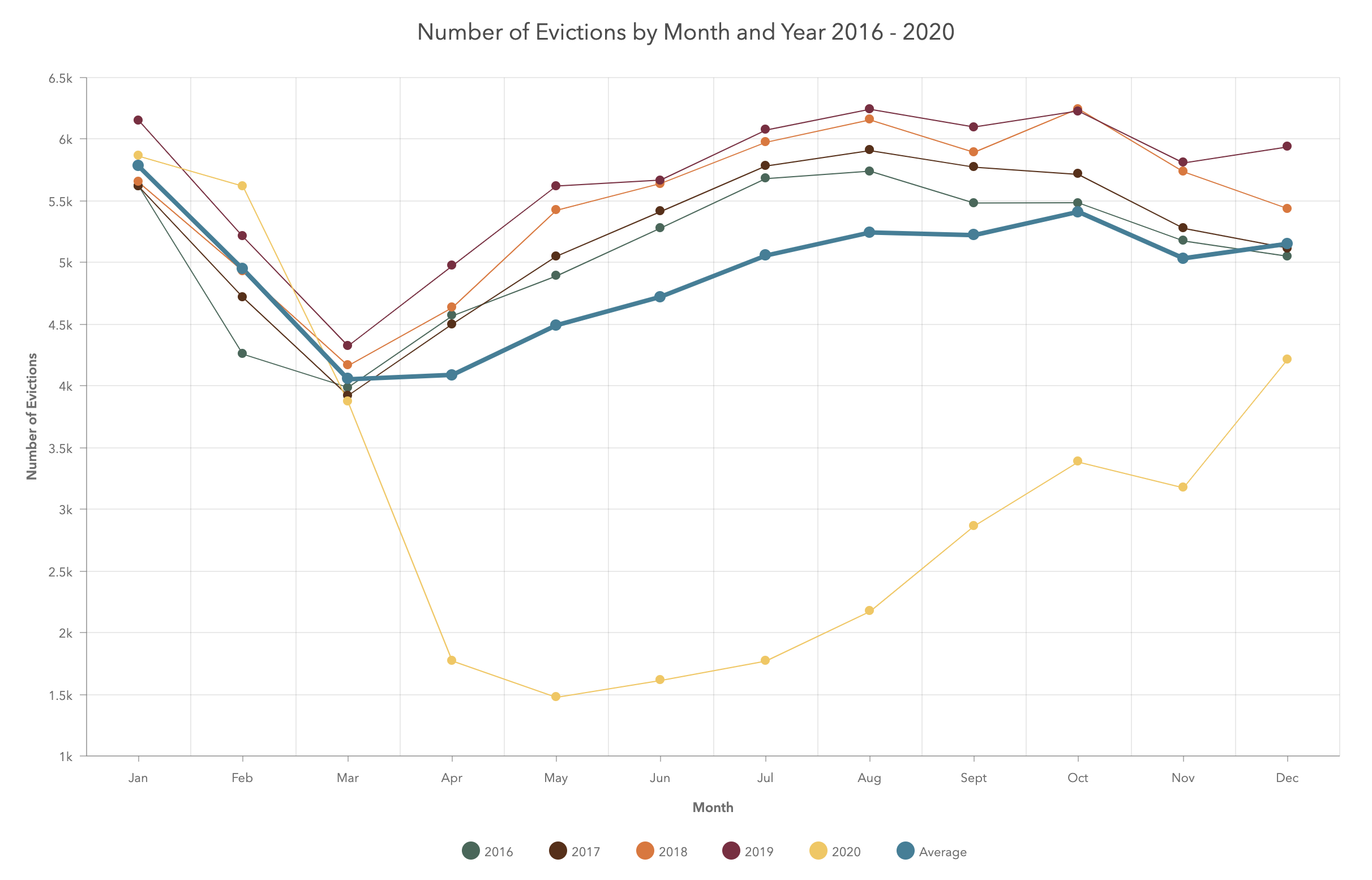

The Maricopa County Evictions Dashboard produced by KER tracks the number of eviction filings in the county each month from 2016 through 2021. Comparing the number of historical eviction filings to the patterns since the pandemic began suggests a backlog of more than 25,000 evictions postponed by the moratorium.

As the pandemic lingers, its effects on income and job loss accumulate, putting an increasing number of households at risk of eviction as savings run out and debt increases. Using a model developed by crosscutting scholars Joffa Applegate and Sean Bergin, KER estimates that by April, 40,000 to 45,000 households could be at risk of eviction all at once.

KER’s Maricopa County Evictions Dashboard tracks monthly eviction filings from 2016–2021. The federal ban on evictions led to a drop in 2020 that experts worry could result in an evictions surge when the moratorium ends.

Organizations like Wildfire, the Society of St. Vincent de Paul and Chicanos Por La Causa have been working tirelessly to distribute emergency rental and utility assistance, as each month, more households become vulnerable to eviction.

“Resources — like direct subsidies to renters to help cover monthly payments during the pandemic — fall far short of demand,” said Deirdre Pfeiffer, an associate professor in ASU’s School of Geographical Sciences and Urban Planning.

Pfeiffer, who conducts housing research and works with local partners to address housing issues, notes that this problem was exacerbated by a lag between allocating and distributing these resources.

Lifting the moratorium before enough renters have received this assistance will likely release a wave of held-back evictions, flooding support systems that may be already overburdened.

“It’s likely you’re going to see more people on the streets and more people looking for assistance,” said Joanna Carr, research and policy director for the Arizona Housing Coalition. “It’s going to impact the need — not only for homeless services — but for emergency food assistance, benefits, et cetera.”

Even if tenants facing eviction find temporary shelter, they face an uphill battle securing future homes. Evictions remain on renter records for seven years.

Then there’s the added concern of COVID-19. “If you don’t have a home, if you’re in a congregate setting, if you’re out in the street, it’s going to be more difficult to maintain public health,” said Tempe council member Lauren Kuby.

Those who do fall ill may struggle to pay for treatment, given the relationship between housing loss and health insurance. A report released last week by New America with qualitative data produced in collaboration with KER found substantially higher housing loss rates in areas with higher concentrations of uninsured households.

“Many low-paying jobs do not provide health coverage, and this finding may indicate that vulnerable households cannot pay for housing and health care, which is especially concerning amid the COVID-19 pandemic,” the report noted.

Making predictions in novel circumstances

Making accurate predictions about the scale of this crisis is no easy task in unprecedented times.

“It's going to be very difficult to predict from past data — or even current unemployment scenarios — because this is a shock that's very different from any other sort of shock that we have experienced,” Applegate said.

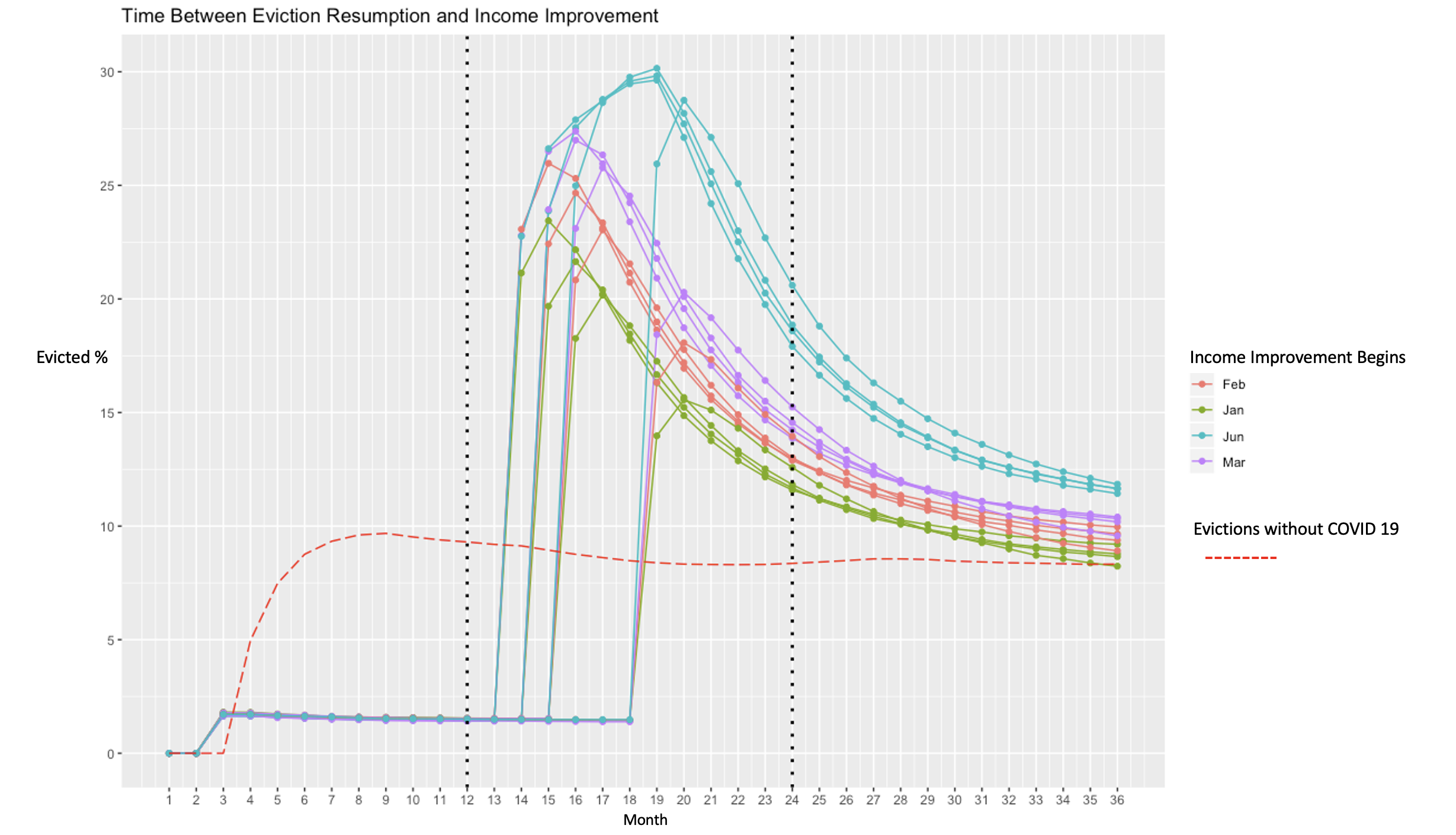

Applegate and Bergin have approached this challenge by using agent-based modeling to understand how changes to variables like stimulus amounts and moratorium end dates could change the relative size of the evictions spike in Maricopa County.

The model suggests that the scale of this surge will be determined more by the speed of income recovery than by the moratorium timeline. The relationship between these two factors could also be crucial.

A deadline that provides breathing room for incomes to fully recover hastens the return to pre-pandemic eviction rates. “Waiting six months after income starts to improve before resuming evictions results in a 10-month faster recovery,” Bergin said.

Additionally, every $500 increase to stimulus checks could keep more than 3,500 tenants in their homes, according to this model.

An agent-based model developed by KER crosscutting scholars Joffa Applegate and Sean Bergin depicts possible eviction scenarios for Maricopa County. It suggests that the size of the surge will be determined more by the speed of income recovery than by the moratorium deadline.

As researchers continue to monitor changes and update their predictions, many organizations are taking the approach described by Carr: “I think my perspective is to expect the worst, which is an evictions tsunami, and to prepare for that as best as we possibly can.”

Tracking evictions for equitable decision-making

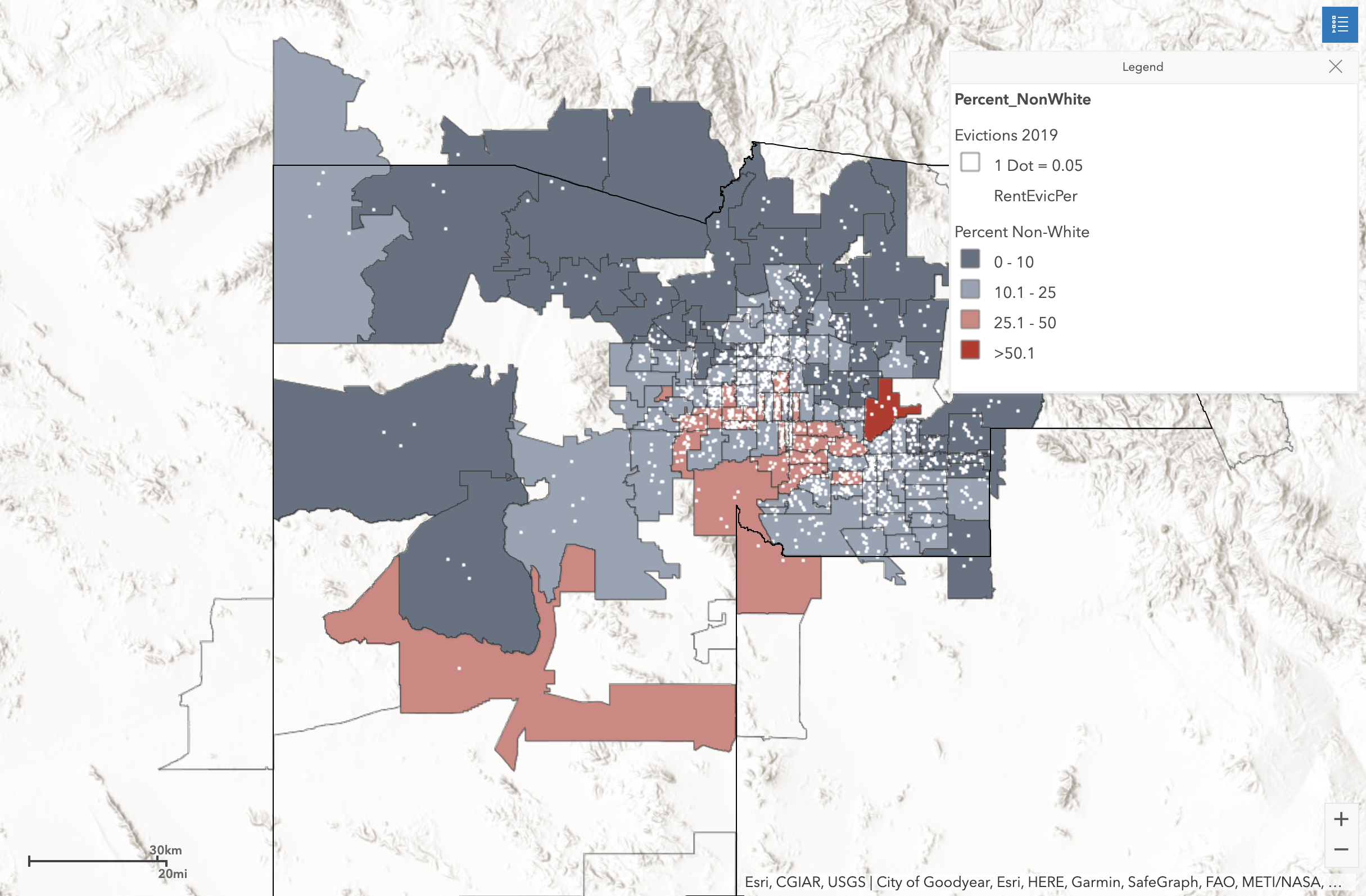

KER’s Evictions Dashboard may prove useful in this regard. In addition to tracking historical trends, it also visualizes demographic patterns in evictions, mapping eviction filings by zip code alongside income and racial breakdowns.

“What we’re seeing on this map is that evictions are often centered around underserved communities and communities of color,” Carr said. “You’re looking at hundreds of years of racism and inequities that are built into these structures.”

KER’s Evictions Dashboard maps evictions by zip code alongside economic and racial demographics, allowing decision-makers and service providers to better target their interventions.

Nationwide, Black and Latina women are disproportionately evicted from their homes, according to an Eviction Lab study. New America and KER found similar trends in Maricopa County and higher rates of housing loss in areas with a higher percentage of immigrants.

“We know evictions and foreclosures persistently affect the same communities, and that the people and places most vulnerable to housing loss before a crisis are often the ones who experience displacement most acutely during harder times,” the New America report noted.

The report, which mapped prepandemic evictions by census tract, found some of the highest eviction rates — up to 30% in one tract — in the Maryvale and Alhambra neighborhoods of Phoenix, which are home to a large Latino population and many low-income renter households.

ASU’s Deirdre Pfeiffer points out that we can expect to see these inequities in eviction lead to greater segregation in the housing market.

“People of color and lower income folks are more vulnerable to eviction, and continuing demand for rental housing — particularly in areas with more amenities — will lead these folks to get replaced by higher income folks,” she said.

“On the flip side, we could see climbing rental vacancy rates and possibly abandonment of rental properties in lower amenity, more poorly serviced areas, where demand may collapse faster than rents.”

Carr believes the Evictions Dashboard can help organizations bridge the disparity in evictions: “When thinking about where do we start, this map will really help because we’ll be able to see where the concentration of eviction is and which neighborhoods are affected.”

This knowledge may help decision-makers and service providers better target their interventions, bringing needed information and assistance directly to those most vulnerable.

“Sometimes you have the most savvy people with access to the internet who will apply for funds, and those who are most in need don’t even have access to apply or know that there’s money out there for them,” said Tempe council member Lauren Kuby.

“So it’s really important to go where people are and to go to faith centers, grocery stores, food distribution sites and provide that information.”

Building a more resilient housing system

Getting financial assistance to the residents that need it and allowing household incomes to recover before ending the moratorium — as KER’s agent-based model suggests — will both be critical if we hope to mitigate this looming crisis. Addressing the underlying weaknesses in our housing system, however, will require us to think bigger.

"When thinking about community resilience, it's important to keep in mind that all of the aspects of our community — things like housing, jobs, food systems, and the climate — are interconnected,” said KER’s Lora Phillips.

"If one aspect of the community, like housing, experiences a huge negative shock, the effects will ripple out, straining resources and impacting well-being for the entire community."

So how might we build a more resilient housing system, one that is less vulnerable to shocks and better able to bounce back and adapt after a crisis?

Setting up a more robust system to collect and share evictions data might be the first step. Some specialists are proposing a federal evictions database to track and map eviction filings and judgments over time.

Then there’s the need to increase the availability of affordable housing. Carr and Kuby both see the restoration of the Housing Trust Fund and the implementation of an affordable housing tax credit at the state level as important steps to take in this direction.

New America and KER also recommend creating community land trusts and limited equity cooperatives to increase affordable homeownership.

“I think we need to empower residents,” Kuby said. “They know what’s going on in their neighborhood more than anybody, and they should be the ones deciding on the mix of housing styles and what they want in their community.”

And because housing is not an isolated system, it will be important to develop holistic strategies that address transportation, education, child care, food, health care and labor.

“One of the most effective ways that we can reduce the number of evictions in Maricopa County is by creating employment opportunities that offer a stable living wage to the people that live here,” Phillips said.

“What we’re really seeing is an inability of some local residents to save enough money to weather shocks like this, and were they able to assemble a nest egg going into this, would be faring much more resiliently in the face of this crisis,” she added.

Still, Carr believes this crisis will ignite change.

“We just need to get through a very rocky few years probably before we start to see it. And we have to keep the momentum; we can’t get comfortable again."

The Maricopa County Evictions Dashboard was created by the Geospatial Research Service in collaboration with KER faculty, including Shea Lemar, Lora Phillips, and Patricia Solis. Explore the evictions dashboard.

More Environment and sustainability

Majority of American religious leaders silently believe in climate change, ASU study shows

Many Americans turn to religious leaders for guidance on matters of faith and morality.With this in mind, a new study, led by a…

A prototype of a university for a thriving world

The challenges for our world’s health and the future of humanity and other life-forms command urgency — and the university is…

From K–12 to corporate upskilling, ASU guides learners of all ages to design a sustainable future

Editor’s note: This story is part of a series exploring how ASU tackles complex problems to create a thriving future.When Kennedy…