Colson Whitehead felt bound to honor survivors while writing 'Nickel Boys'

Author Colson Whitehead felt a responsibility to stick to the truth when he wrote the terrible events in “The Nickel Boys,” the best-selling 2019 novel for which he won his second Pulitzer Prize.

The book is based on the real-life Dozier School, a reform school for boys in Florida, and “The Nickel Boys” tells the story of two Black boys who were there in the early 1960s. One manages to escape and, decades later, faces the trauma he endured.

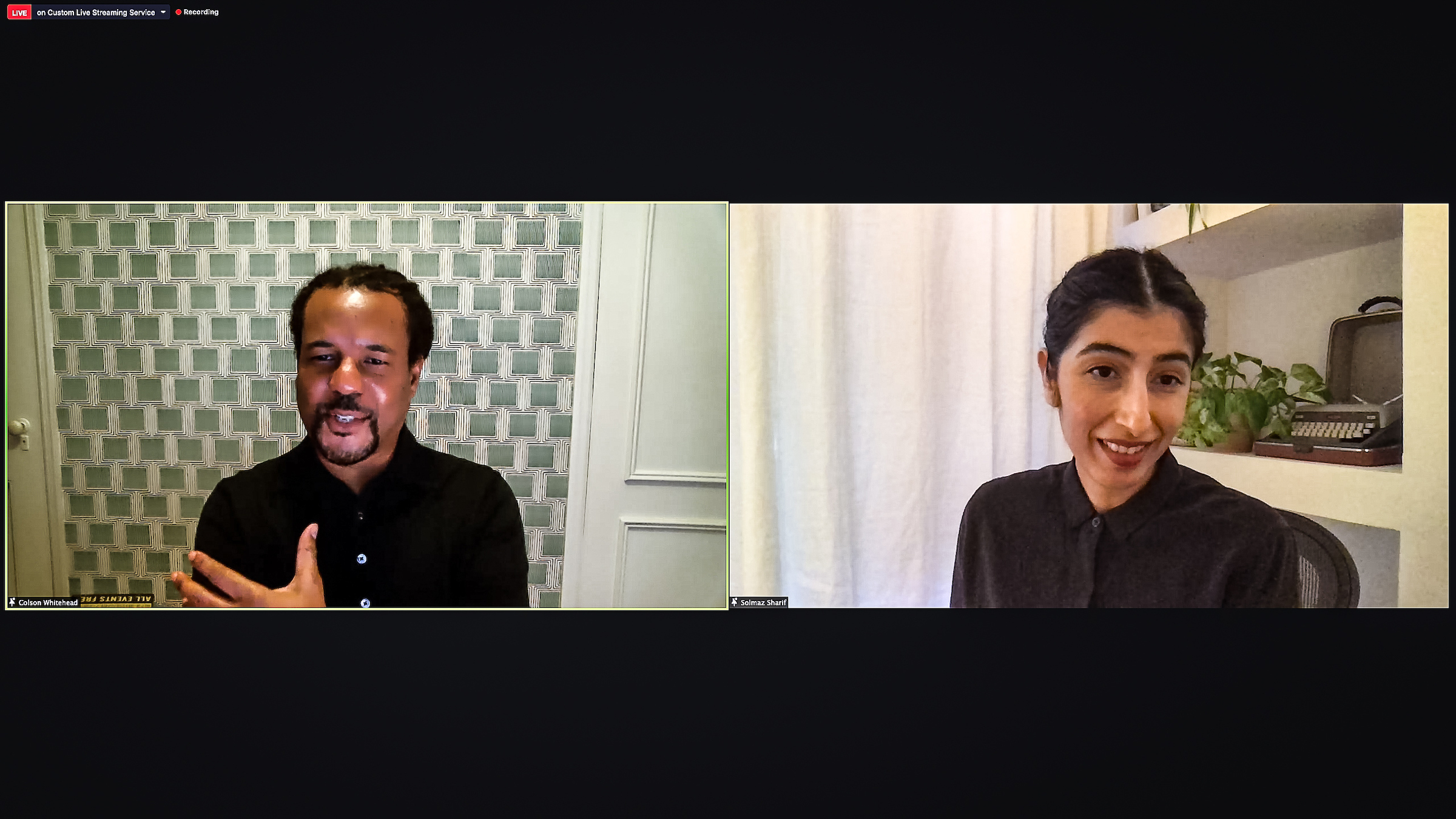

“I kept close to the history of the school because I wanted to honor the people who had been there,” said Whitehead, who spoke to the Arizona State University community on Jan. 27 for the Jonathan and Maxine Marshall Distinguished Lecture Series. The livestreamed event was a conversation moderated by Solmaz Sharif, a poet and assistant professor of creative writing.

He described how he came across the story of the Dozier School, and how “The Nickel Boys” balances the hope and cynicism he felt during the past few years.

In the summer of 2014, he was scrolling through Twitter when he saw a news report about the school, which had been the subject of many abuse investigations before it finally closed in 2011. The article reported that during an excavation of the property, an unmarked grave containing 55 bodies was found.

“Some died of pneumonia, some had blunt-force trauma to the skull, some had shotgun pellets in their chest,” he said.

For years, families of boys who were sent to the school, as well as survivors, had told of the abuse. Most of the people who spoke out were white, although most of the boys at the school were Black.

“I wondered what happened to the Black kids. Their voices were not present,” Whitehead said.

“So I started thinking what kind of story I could get out of this situation.”

Author Colson Whitehead spoke to the ASU community in a talk moderated by Solmaz Sharif, an assistant professor of creative writing and a poet. Screen grab by Charlie Leight/ASU Now

He described how he developed the two main characters, Elwood and Turner.

“Elwood came first. I knew I wanted a kid who didn’t belong there,” he said.

“I knew he would be a straight arrow, an audience proxy, so we see the world through his eyes.

“He’s a stand-in for a lot of brown boys and Black boys who leave their houses, have an encounter with law enforcement and in that moment, their lives are changed.”

Elwood hitchhikes to class and when a policeman pulls them over, discovers the car is stolen. He’s sent to the Dozier School, where he still maintains an optimistic outlook.

“Once I had Elwood, it called for the opposite. In terms of pure storytelling, it’s the necessity of a foil,” he said.

Turner, an orphan, is at the reform school because he has nowhere else to go.

“People don’t change,” Whitehead said of Turner’s outlook. “You can’t change the social order. All you can do is survive and get through the day without getting beaten up.”

Elwood and Turner embody the current philosophical dilemma of the country, he said.

“For the last four years a lot of us were wrestling with how much we believe America can change,” he said.

“A lot of us vacillate between hopefulness and hopelessness across a day, a week or a life.”

In researching “The Nickel Boys,” Whitehead read newspaper articles, scholarly documents (including accounts by the University of South Florida, which did the archeological excavation) and memoirs.

He described how he kept some details and, as a fiction writer, was free to invent others. For example, the shed where boys were horrifically beaten at the Dozier School was called “the White House.”

“You can’t really compete with ‘the White House,’ so I kept that name,” he said.

The boxing match in the book was made up.

“In real life, the ham radio club at the Dozier School was very popular. Am I going to get a lot of drama out of the ham radio club? Maybe, but with a boxing match, I can expand on that and pull different threads out.”

The boys were subjected to terrible violence, but Whitehead didn’t go into much detail about it.

“There’s a main scene where Elwood goes to the White House and is beaten,” he said.

“It’s a five-page scene. You never see the strap hit him. All the tension comes from the other kids before him. He hears their screams. There’s a reader dread.

“The scene of abuse has to be there. That’s being true to life. I’m not going to shrink away. I’m not going to exploit it.”

He compared that to “The Underground Railroad,” the best-selling 2016 novel for which he won his first Pulitzer Prize.

“With ‘Underground Railroad,’ I’m reading enslaved peoples’ accounts of their enslavement in which they explain the most terrible things in the most deadpan style,” he said.

“There’s no need to dramatize it. That sort of flat description became part of ‘Underground Railroad.’ I didn’t need adjectives.”

“Underground Railroad” is being made into a miniseries by Barry Jenkins, the director of the 2016 movie “Moonlight,” which won the Academy Award for best picture.

Whitehead visited the set in Georgia just before the pandemic locked everything down and was amazed at how his book was transformed into a drama for the screen.

“I had a character I referred to as ‘John’s son.’ On set, they introduced someone to me saying ‘He’s playing Larry.’ And I’m like, ‘Who is Larry?’ Well if you make a movie, you can’t just have ‘John’s son,’ ” he said.

“They named people who appear for one paragraph, and there’s a real actor on set for like a month.”

Whitehead said he learned from other writers that once he gave permission for the miniseries, it no longer belonged to him.

“It’s not my thing anymore. It’s their vision. I trust him,” he said of Jenkins.

Whitehead said that even after 10 books, he still has moments of struggle when he writes.

“Before I start writing, I plan things out. I know the beginning and the end but the middle can be fuzzy,” he said.

“The narrative voice will take like 80 pages to congeal. I know what happens but I don’t know how the narrator walks and talks.”

When he gets stuck, he’s patient.

“I do some research to get kicked out of my rut,” he said. “I’ve written enough books to know that it might take a week or a month or some long walks but I will unblock the problem.

“The work is always hard and that’s what makes it interesting and compelling.”

Top screen grab by Charlie Leight/ASU Now.

More Arts, humanities and education

ASU instructor’s debut novel becomes a bestseller on Amazon

Desiree Prieto Groft’s newly released novel "Girl, Unemployed" focuses on women and work — a subject close to Groft’s heart.“I have always been obsessed with women and jobs,” said Groft, a writing…

‘It all started at ASU’: Football player, theater alum makes the big screen

For filmmaker Ben Fritz, everything is about connection, relationships and overcoming expectations. “It’s about seeing people beyond how they see themselves,” he said. “When you create a space…

Lost languages mean lost cultures

By Alyssa Arns and Kristen LaRue-SandlerWhat if your language disappeared?Over the span of human existence, civilizations have come and gone. For many, the absence of written records means we know…