It was the viral image of activist Allie Young leading a group of Navajo voters to an Arizona polling station on horseback that really drove it home for Diné poet Jake Skeets.

“That to me is empowerment of the people for sure, and it really is the power of community-based organizing,” he said.

Without question, the swell of Indigenous voters who turned out to cast their ballots in the 2020 U.S. presidential election were instrumental in swinging the state to a victory for Joe Biden. But as Skeets alluded to, doing so took work; it meant coming together to overcome a host of barriers, including poor access to voter registration offices and polling stations, limited transportation and excessive mail delays, all of which amount to voter suppression.

Given what they were up against, the sense of empowerment Skeets described that resulted from their success is well-earned.

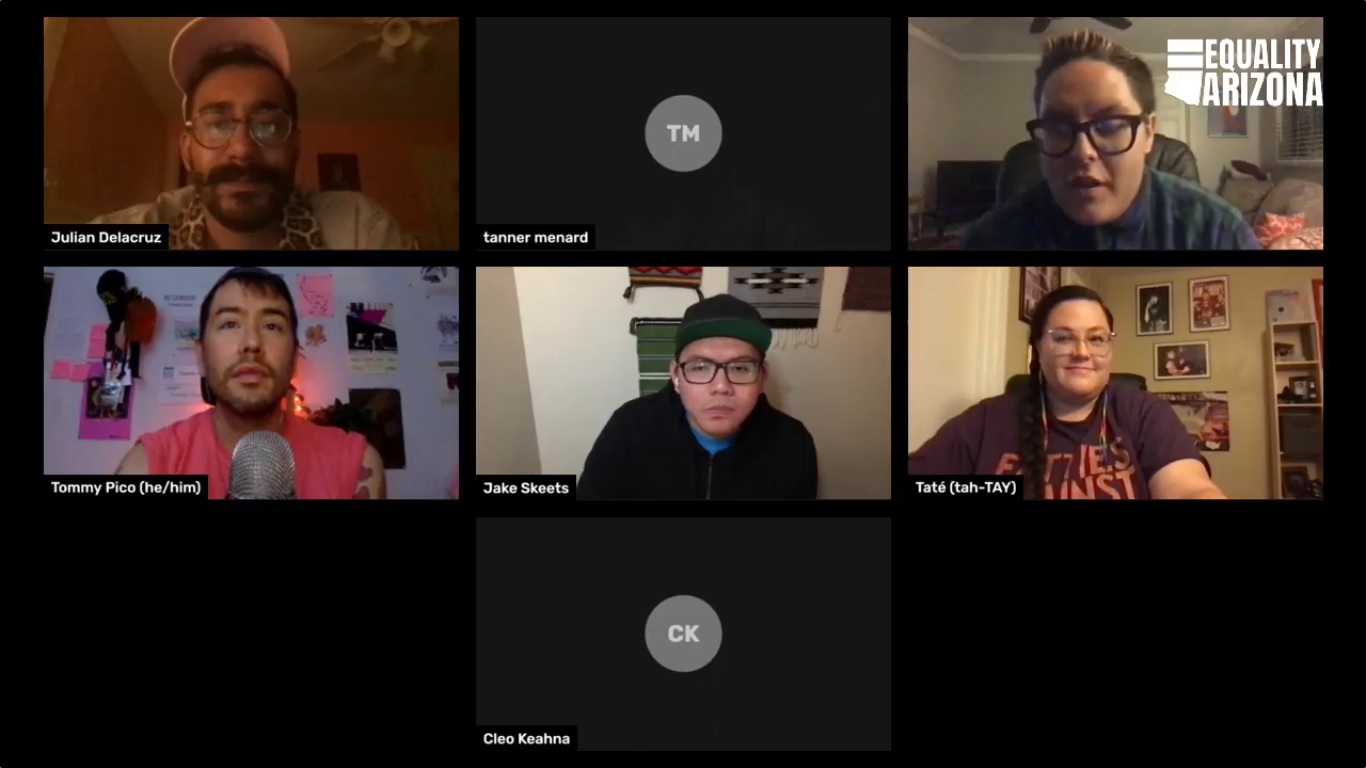

That same belief in the potential of community-based organizing was apparent at the December meeting of the Queer Poetry Salon, a partnership between ASU’s Virginia G. Piper Center for Creative Writing and Equality Arizona that aims to strengthen and grow queer culture in Arizona by hosting quarterly readings of works by world-renowned LGBTQ poets and writers.

December’s salon featured all Indigenous writers, including Skeets, who in addition to being a nationally recognized poet also holds a position as an associate professor at Diné College in Tsaile, Arizona, and was recently named one of this year’s Mellon Projecting All Voices Fellows by the ASU Herberger Institute for Design and the Arts and ASU Gammage.

Also featured were poets Tommy “Teebs” Pico, a citizen of the Kumeyaay Nation from the Viejas Indian Reservation in San Diego, California; Smokii Sumac, a member of the Ktunaxa Nation located in the Canadian province of British Columbia; and Taté Walker, a citizen of the Cheyenne River Sioux Tribe located in South Dakota.

The significance of December’s salon, which in essence served as a space for members of two marginalized communities – Indigenous and queer – to safely gather and express themselves, was not lost on the attendees. Though Skeets reported that queerness in his own Navajo Nation is “thriving in the larger scope of things,” he also acknowledged that “many still feel unsafe in their own families and communities.”

“It’s mostly due to the colonial and brutal language that our own government emulates from the U.S. government,” Skeets said.

Skeets sees his work, much of which he shared during the salon, as a means of “undo(ing) and reimagin(ing) a colonial and brutal language like English.”

“I like to think of queerness as an undoing and reimagining of heteropatriachy that drives much of the U.S. way of thinking and doing things,” he said. “This often leads to violence, which is what we are seeing today. Queerness is a resistance to that.”

tanner menardtanner menard uses they/them pronouns and doesn't capitalize their name., civic programming organizer for Equality Arizona and a poet themself, created the Queer Poetry Salon about a year ago with a similar spirit.

“I think that people finally being in a position where they feel safe enough to (share deeply personal work) in a place like Arizona, that is dangerously conservative and where some people are still violently oppressed, it can be a very powerful tool for queer people, and also people who are not queer to express their allyship,” menard said in an interview for a September ASU Now story announcing the partnership between the Piper Center and Equality Arizona.

Diné poet Jake Skeets (center) was featured at the December meeting of the Queer Poetry Salon.

Skeets and menard met several years ago, and when the former learned of the latter’s endeavor, he was all in; Skeets has participated in several Queer Poetry Salons over the past year and was especially thrilled to be a part of December’s Indigenous-centered salon.

“I do think these kinds of spaces create community and empower those to feel at home,” Skeets said.

During the hour-and-a-half-long event, he read a number of poems, both new and old. One, from his first collection of poetry, “Eyes Bottle Dark with a Mouthful of Flowers,” is titled “Drift(er).” It’s about his uncle, Benson James, whose image graces the cover of the collection. The black-and-white photo was taken in the summer of 1979 by fashion and portrait photographer Richard Avedon, who came upon James in the streets of Gallup, New Mexico, while working on a project focusing on people in the American West. A year later, James was murdered.

“Gallup is a very strange place,” Skeets told the salon attendees while introducing “Drift(er).” “It’s a border space, so of course violence against Native people is very high in those parts of the country. But it’s where I grew up.”

Skeets’ apparent reckoning with that conflict — the love one feels for their home, even when it does not always embrace them — was echoed in works of other poets throughout the evening.

In Walker’s poem, “I Like Your Accent,” theyTaté Walker uses they/them pronouns. call out to “all the folks with names too thick and too sticky for colonized tongues to dominate,” reminding them that “your sticky thickness tastes like honey to the ones who named you.”

Still others celebrated their gender and sexual identities. Sumac read from a poem in which he compared embracing his sexuality as “like sitting in a cart waiting for a rollercoaster to begin.” In another, he advocated “for the love of all that is queer and brown for the beautiful disabled bodies … for all of our love, which can never be wrong.”

Clearly moved by their words, Skeets took a moment before he began his own reading to proclaim that he was “incredibly honored” to share space with them that evening. He also hinted that there may be a sophomore collection of poetry in the works, though he told ASU Now via email after the event that he doesn’t expect it to be a huge departure from his debut.

“My new poems are still very much informed by the landscape of the Navajo Nation but in a different context,” Skeets said. “My first book relies on the fields around Gallup and the field of the page to ground readers and myself in a narrative of trauma and beauty. My new poems are using landscape as a mapping tool and I’m able to hone in on certain parts of the reservation and conjure narrative and language. I am also thinking that it may serve as somewhat of a sequel to my first book. I’m not sure if poetry collections can have sequels but I am very much envisioning a picking up where the first book left off.”

He's also in the process of working with Phoenix-based WarBird Press and ASU’s Herberger Institute on a new text/image project as part of his work with the Mellon Projecting All Voices Fellows Fellowship, which he expects to be able to share with the public in spring 2021.

As for the Piper Center, its commitment to uplifting a diversity of voices continues to manifest in its hosting of such events as the NEA Big Read, a 30-day celebration of Indigenous culture and literary arts featuring over 25 performances and panels throughout March of 2021.

Top photo courtesy of Pixabay

More Arts, humanities and education

Upcoming exhibition brings experimental art and more to the West Valley campus

Ask Tra Bouscaren how he got into art and his answer is simple.“Art saved my life when I was 19,” he says. “I was in a dark place and art showed me the way out.”Bouscaren is an …

ASU professor, alum named Yamaha '40 Under 40' outstanding music educators

A music career conference that connects college students with such industry leaders as Timbaland. A K–12 program that incorporates technology into music so that students are using digital tools to…

ASU's Poitier Film School to host master classes, screening series with visionary filmmakers

Rodrigo Reyes, the acclaimed Mexican American filmmaker and Guggenheim Fellow whose 2022 documentary “Sansón and Me” won the Best Film Award at Sheffield DocFest, has built his career with films that…