Have you taken your temperature recently? Was it lower than the standard 98.6 degrees Fahrenheit?

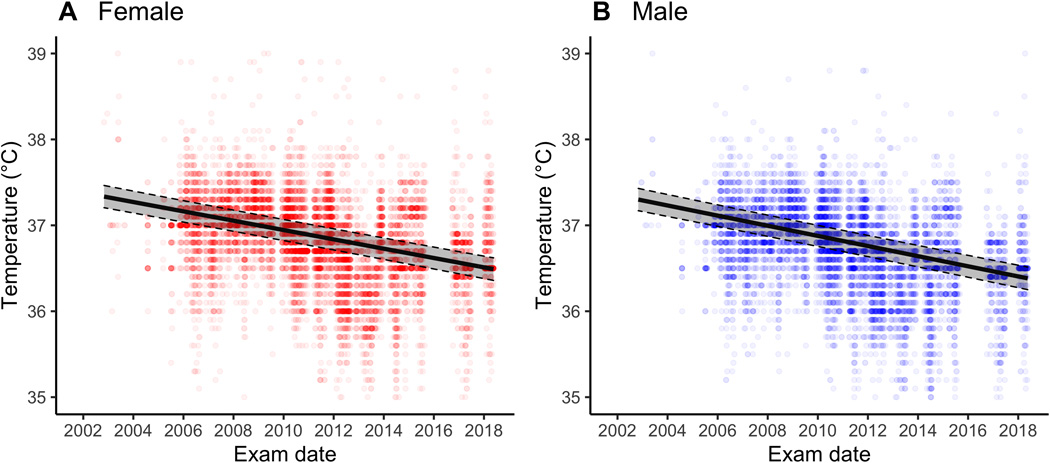

Research published earlier this year indicates “normal” body temperature has been steadily decreasing in the United States over the last 200 years, now hovering around 97.8 degrees. Similar trends were reported in studies from the United Kingdom.

New research not only found the same decrease in remote populations of people living in the Bolivian Amazon, but the decrease in body temperature took place over a mere 20 years.

The study was published by a transdisciplinary team, including Arizona State University anthropologist Benjamin Trumble. Their findings show rapidly decreasing body temperatures among the Tsimane people, living in remote communities in the rainforests of Bolivia.

“The finding of lower-than-expected body temperatures in the U.S. had a lot of people scratching their heads,” said study author Michael Gurven of the University of California, Santa Barbara. “Was this a fluke? Here, we confirm that body temperatures are below 98.6 degrees Fahrenheit outside of places like the U.S. and U.K. The area of Bolivia where the Tsimane live is rural and tropical with minimal public health infrastructure.”

Researchers are unsure why the change in the Tsimane population body temperature is so rapid, but the Tsimane have undergone other rapid changes as well. Increased exposure to larger nearby market towns has impacted many facets of everyday life for the Tsimane. For example, some Tsimane communities close to the town San Borja now have access to electricity.

General societal advancements may point to why we’re seeing this trend. For example, in the U.S., body temperature started decreasing after the industrial revolution. Access to running water in people’s homes and increased availability of medical care could lessen the prevalence of infection and disease and cause body temperatures to decrease.

Among the Tsimane, decreased body temperature could be a result of increased interactions with larger towns — leading to more antibiotic use, and better access to warm clothing and insulated housing. Changes in parasitic infection rates may also affect body temperature. Trumble notes there is no “silver bullet,” or one factor to which the decrease can be attributed.

Other factors that may impact body temperature in the Tsimane are changes in body fat percentage, physical activity and sleep patterns.

These temperature studies could have major implications for global health. Our body temperature is easy to measure and can be used as an indicator of overall health. Both in the U.S. and in Tsimane communities, the decreased body temperature has coincided with increased life expectancy.

Expanding medical data

Trumble notes the majority of our medical data comes from studies conducted in the U.S. or Europe. This information forms our foundation of what is considered “normal,” but for most of human history, we lived in a nonindustrial environment.

“If you compress the last 5 million years of human evolution into a single year, we were hunter-gatherers on Jan. 1, March 1 and so on, all the way until Dec. 31 at 11:40 p.m.,” Trumble said. “That’s when the industrial revolution happened.”

Human evolution provides important context in studying human physiology and changes in health over time and in our current populations. By better understanding health in nonindustrialized populations, researchers can achieve a broader view of how humans interact with and adapt to their surroundings, and better understand variation in global health.

“Right now, we’re operating way outside of the manufacturer’s recommended usage,” Trumble said. “Meaning, our bodies didn’t evolve to sit in chairs in front of computers.”

Tsimane Health and Life History Project

The Tsimane live in about 95 communities in remote, forested locations in Bolivia, largely living off hunting and foraging. Few communities have access to electricity but none have access to running water.

The Tsimane Health and Life History Project was founded 16 years ago. The team has received funding from the National Institutes of Health to study healthy aging, specifically cardiovascular health and Alzheimer’s disease. This team is composed of a mobile medical team of Bolivian doctors, a Bolivian biochemist and Tsimane community members trained as anthropologists. This group of experts provides free health care to the Tsimane, and, with approval from community members, conducts specific health-related studies. Research is largely led by co-directors Hillard Kaplan, Gurven, Trumble and Jon Stieglitz.

The research, “Rapidly declining body temperature in a tropical human population” is published in Science Advances.

More Science and technology

Project Gen Z asks whether college teaching is working for current students

Are best practices in college biology teaching, built on 30-plus years of research, working for Gen Z students? That is the…

From wannabe high school math teacher to Regents Professor

It’s a bit difficult to describe the work Stephanie Forrest does as director of Arizona State University’s Biodesign Center for…

Regents Professor recognized as pioneer in educational technology

Reading can transport people around the world — and back and forth in time.That’s what Danielle McNamara has helped tens of…