By now incoming first-year students at Arizona State University will have discovered where their classes are and other vital info, like the nearest Starbucks. This is the week they will begin to look up from their phones and notice campus.

It’s big, yes. And the architecture is all over the place. It’s been called a world’s fair of styles. New buildings are more and more high-tech. Renderings for ISTB7 — under construction at University Drive and Rural Road on the Tempe campus — show little robots performing tasks in the lobby.

But Old Main, the three-story red brick Victorian pile with the balcony and elegant staircase on University Drive, jumps out because of its appearance and age. ASU has very few buildings that old.

Old Main is the heart and soul of the university. Designed by a gun-slinging principal, it was built — as the new buildings are built now — as a sign of progress, of embracing the future. One of the most important events in the history of the Valley of the Sun took place at Old Main. As campus grew, it became neglected and abused — a place where junk was stored, literally. Restored in the early 1990s, it now serves as a vital tether to the past.

There are hundreds of places on campus to shoot a cap-and-gown photo at graduation. But, every semester, without fail, hundreds of new grads flock to the oldest spot on campus to have their matriculation recorded. According to Old Main building manager Mike Tomah, it is the most-photographed building in the state of Arizona.

You may end up there too. Read on. You may see something of yourself in its history.

Dwayne Martin-Gomez, 2019 spring graduate, and his family at Old Main. Photo by Charlie Leight/ASU Now

Not the first

The first building on campus was the Territorial Normal School, built in 1885. (It no longer exists.) A one-story brick building, 60 feet by 70 feet, it was built in Territorial style, with a deep porch surrounding it to keep it cool. The caretaker and his family lived in part of it. Students lived off campus. Room and board was provided by private families at $5 to $6 per week.

In 1885, you could graduate in 22 weeks. You had to be at least 16 and have a high school diploma. Tuition was $4 per month, unless you promised to teach after graduation or were nominated by a member of the territorial legislature, then it was free. If you chose the former, you had to swear an oath you would teach “for a reasonable length of time.”

Some did. Some, like first class alumnus James McClintock, did not. They put in a year or two and decided teaching wasn’t for them. (McClintock taught for three years and then went into the newspaper business, among other endeavors.) McClintock Drive, McClintock High School and McClintock Hall at ASU are all named in his honor. McClintock was one of the five graduates who made up the first graduating class of the Normal in 1887.

When McClintock attended the Normal, the "library consisted of a dictionary, and the apparatus was a nice terrestrial globe — nothing more,” he said years later. “Drinking water was to be found in an olla (a large mouthed pot) by the side of the front door. The water came from a well equipped with bucket and rope. Near it was the lavatory, comprising one tin basin."

You may have noticed students gunning their engines on University Drive. That’s nothing new.

"Almost everyone rode to and from school on horseback,” McClintock said. “Many were the spirited races run on what is now known as Eighth Street, and occasionally one of the students would ride an unbroken colt to school that he might contribute to the gayety (sic) of the day's session."

The first year all the students but one were from Arizona. (Julia A. MacDonald, 26, was from St. George, Utah.) A handful were from Zenos – a name Mesa held for a few years.

The “architect” of Old Main was a Normal School principal, 27-year-old Edgar Storment, who started work in Tempe in 1892.

Before Tempe, Storment taught at a rural school called Agua Caliente, just south of the Gila River. It was a rough place, and he kept a revolver in his desk. When students got out of hand, he’d pull it out at lunchtime and shoot a few targets as a message.

Like the three Normal principals before him, Storment had no help — or money — from the legislature. He dreamed of a brand-new, three-story brick palace for the school and drew up the plans himself. (Sadly, the hand-drawn sketch is long lost.)

The student body was outpacing the four-room original building. (It sat where Life Sciences A now sits, across from the Virginia G. Piper Writers House.) Between 1886 and 1900, the student population had ballooned from 33 to 131.

The Normal School Board approved Storment’s plan, resolving “to erect a three-story, fireproof building, the lower story being of brown stone, 12 feet high, 10 feet above and 2 feet under the ground, the two upper stories to be constructed of such materials and to such heights as may hereafter appear best.”

It was going to be much bigger than the original building, and with all the latest features. Contemporary descriptions read like marketing materials from a mass-production home builder: “beautiful inner stairways, the unprecedented plumbing, and other last-word features.”

A new face on the Old West

When the Tempe Normal School was founded in 1885, the shootout at the OK Corral was four years in the past. The Apache Wars ended with Geronimo’s surrender a year after the school was founded. Arizona had a horrible national reputation: a territory with no hope of becoming a state.

And the Normal School, with its Territorial-style building, screamed “frontier.” That was a look folks like Storment wanted to banish to the past.

“There was a new generation of folks moving West,” University Librarian James O’Donnell said. Since arriving at ASU in 2015, O'Donnell has led a push to showcase the university’s history, making it more accessible and engaging, both online and in person.

“This was the stage when the lawyers and the schoolmarms come to town,” O’Donnell said. “There came a point when all of these communities said, ‘No, we’re going to be something here. We’re going to be cultured and civilized and do stuff right.’ And they did. And it’s a beautiful thing to see.”

If Tempe Normal School was not a venerable institution, it wanted to at least look like one. Overcoming Arizona’s Wild West image was the point of buildings like Old Main.

“They were designed to have ivy climbing up them like Harvard,” university archivist emeritus Rob Spindler said in an interview a few years ago. “They’re saying, ‘Look at the Old Main fountain; we have water. It’s safe to send your kids here.’”

The money pit

Construction was a disaster. Starting in January 1893, it lasted five years, with one problem after another.

Lousy materials. Contractors and workers fighting over pay. Wait periods between income tax payments. A plot successfully cooked up by a shady contractor to make off with $4,000 of local investors’ money. Bad weather.

It took a number of architects, slews of contractors, and, finally, intervention by leading citizens of Tempe to sort out the legal and financial problems.

When it was finished in February 1898, it contained 12 classrooms, a large study hall, a stage and auditorium, wide halls on each floor, and administrative rooms. It was the first building in Tempe to have electric lighting, and it was the tallest building in the territory.

1898 photo of students on the steps of Old Main. Note the dirt at the foot of the brand-new building. Courtesy of ASU Library

Not an original name

The building’s name strikes O’Donnell because it’s not unusual.

Penn State, the University of Arkansas, Wayne State, Augustana College, Central Michigan University, Gale College, Marshall University, Franklin & Marshall College, the University of Colorado at Boulder, Western Washington University, the University of South Dakota, North Dakota State University, Illinois State and Baylor University all have Old Mains. (And that is a superficial list.)

They tend to be handsome, solid, old buildings.

“The historical question I wish I knew the answer to was who was the first institution to call their building Old Main?” O’Donnell said. “Lots and lots of places have a building like that. It says something about how in the early days you’re doing this education thing, you’re doing this college thing, and you make a building that says how serious you are, that makes a splash, that makes people go ‘Whoa! OK.’”

Undated photo of a classroom in Old Main. Courtesy of ASU Library

The bull moose bellows

It’s March 20, 1911. Former President Theodore Roosevelt is in town for the dedication of the Roosevelt Dam 60 miles northeast of the Salt River Valley. His trip to Tempe is only intended to be two or three minutes long, and he’s expected to speak standing from his car.

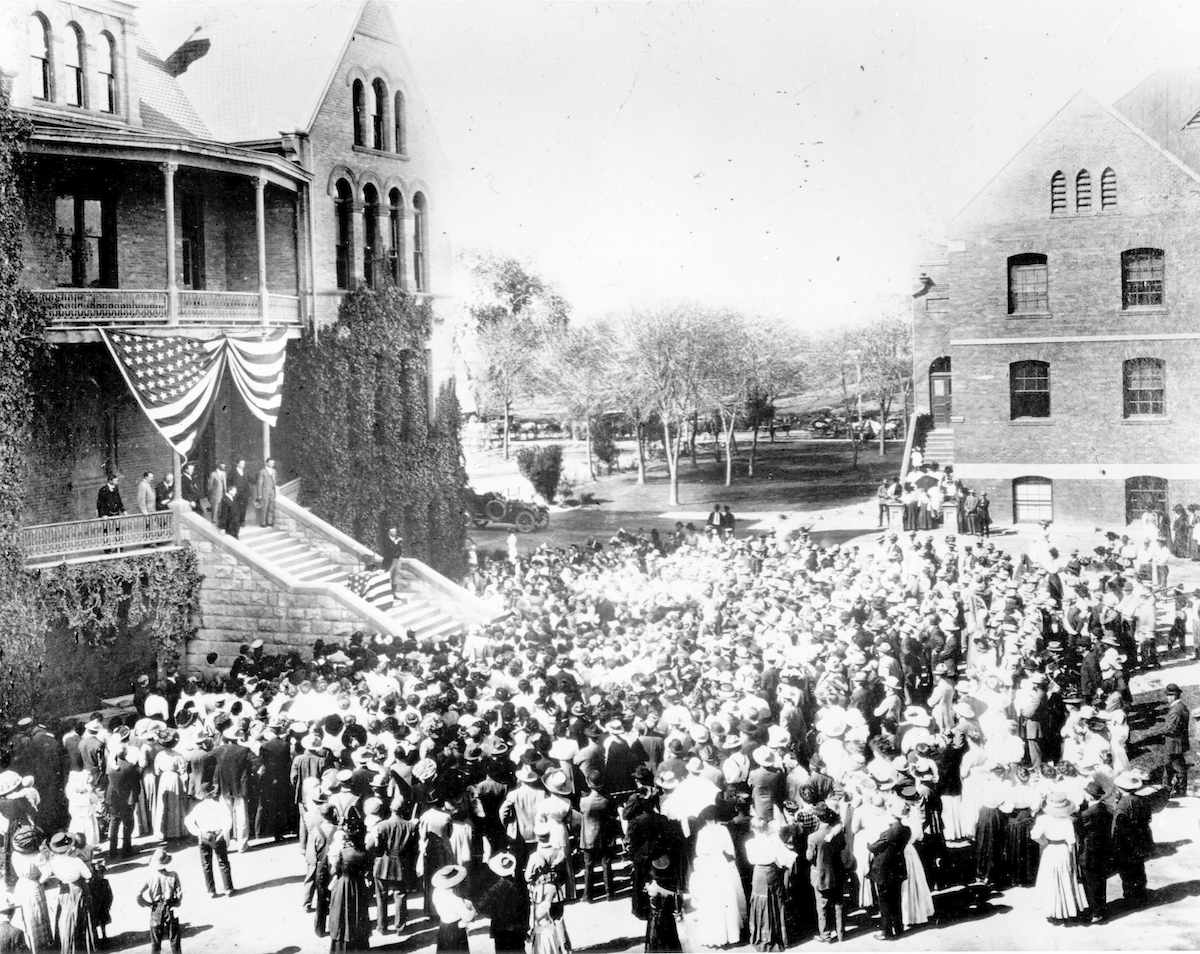

But when he arrives at the campus of Tempe Normal School, he is greeted by hundreds. A huge flag hangs from the second-floor balcony of Old Main. Roosevelt bounds up the steps (he rarely does anything slowly) to the first landing, where he speaks for 13 minutes in his patrician New York accent.

Former U.S. President Teddy Roosevelt speaks to the students of Tempe Normal School from the steps of Old Main before the dedication of the Roosevelt Dam in 1911. Photo courtesy University Archives, Arizona State University Libraries

He speaks about the importance of an educated citizenry and says the dam and the building he stands in front of are signs that Arizona has left its wild past of gunfights and massacres behind. The territory is finally ready to earn its star on the flag and become a state.

“It is a rare pleasure to be here, and I wish to congratulate the Territory of Arizona upon the far-sighted wisdom and generosity which was shown in building the institution,” Roosevelt said. “It is a pleasure to see such buildings, and it is an omen of good augury for the future of the state to realize that a premium is being put upon the best type of educational work.”

Grady Gammage Jr. is a part-time academic, practicing lawyer, author, sometime real estate developer and elected official. At ASU he is a senior fellow at the Morrison Institute and an adjunct professor in the Sandra Day O'Connor College of Law. His father was the ninth president of ASU. He is also the last living person to reside at the President’s House, now the Piper Writers Center.

“Arguably the single most significant event in the history of Phoenix is the dedication of Roosevelt Dam,” Gammage Jr. said. “The population we have in Phoenix today would not be possible without that happening.”

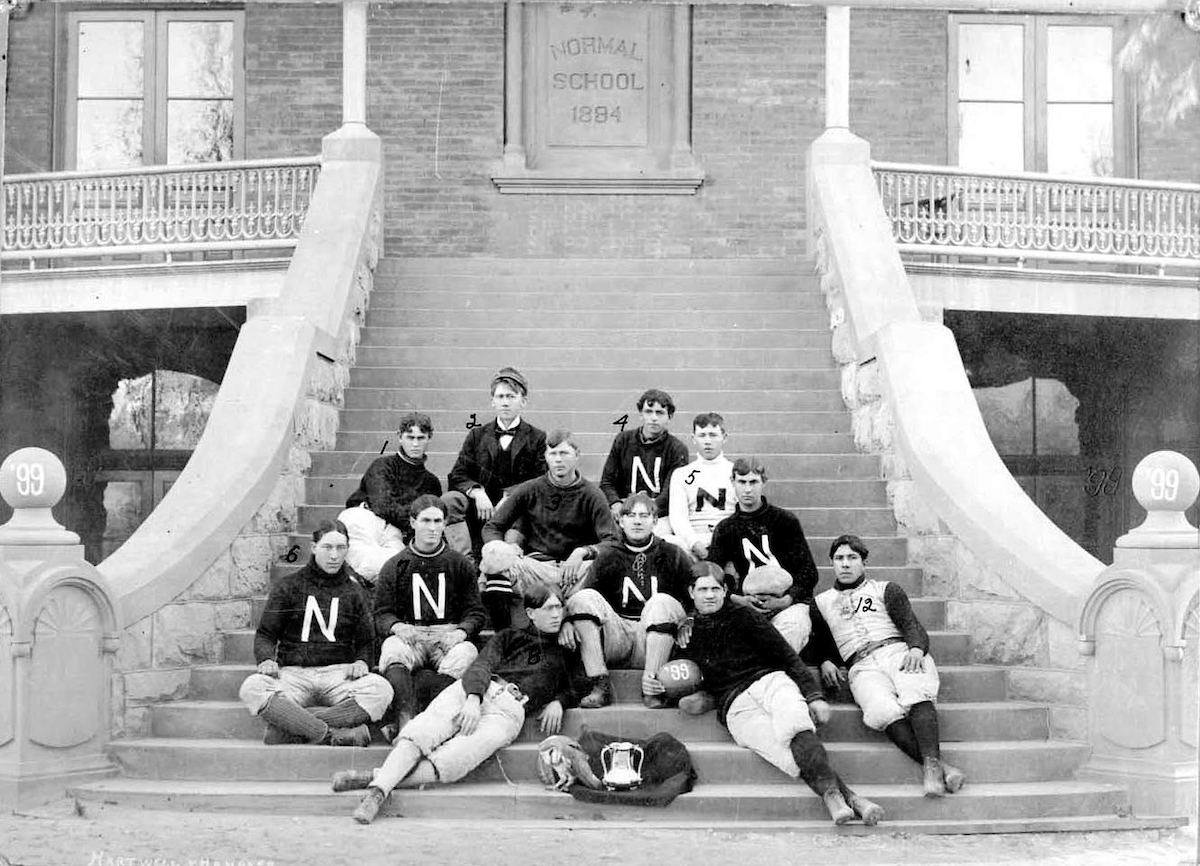

The 1899 Territorial Cup-winning Tempe Normal School Football team's portrait on the steps of Old Main. Photo courtesy of the ASU Library

The heart of campus

The pond and fountain in front of Old Main was constructed with river rock and pipe and first appeared in the 1912 school annual "The Fountain." Over the years the pond was used for everything from growing water lilies to dunking freshmen. The fountain was replaced with a new fountain designed by the Depression-era Works Progress Administration artist Emory Kopta.

Five women sit on the fountain in front of Old Main at Arizona State University in Tempe, circa 1940. Courtesy of ASU Library

In those days students gathered on the second-floor balcony to sing a piece called “In the Vale of Old Tempe,” the lyrics of which nostalgically allude to Old Main and the Old Quad.

For half a century almost every student took classes in Old Main. By 1933 the east half of the main floor was converted to a recreation hall. Military science, ROTC and aerospace studies academic offices were located at Old Main as early as 1963, and Telephone Services was established on the first floor in 1976.

Until 1952, the building was a critical part of the school. It housed at various times an assembly space, library, museum, auditorium, dedicated geography and music classrooms, conventional classrooms, laboratories and even an armory. As new buildings sprang up, more and more rooms were converted to classrooms and faculty offices.

Undated photo of a study hall in Old Main. Courtesy of ASU Library

Decrepitude

By 1952, though, the building was in bad shape. The outside stairs and balcony were falling apart, but money was tight. President Grady Gammage consulted with university architect Kemper Goodwin. As a slapdash fix, the stairways were torn down and a modern façade slapped on that unfortunately killed the 19th-century charm.

“It was really ugly,” Gammage Jr. said. He also described the fix as a “brick plug.”

After 1960, Old Main was just an aging building with a modern façade. And while urban renewal was in full swing during that decade, historic preservation was not. “Old” buildings were seen as hindrances to progress. Inside, Old Main had been chopped up into a rabbit warren of small rooms. The ballroom had a drop ceiling. Junk was stored inside. No one sang there.

Even so, the neglected structure was added to the National Register of Historic Places in 1985.

Atonement

In the early 1990s, the main phone switch for the campus, located in Old Main’s basement, needed to be updated.

“The decision was, 'If we’re going to do this, we might as well do some preservation,'” said Gammage Jr. “I felt my being involved in the campaign would atone for what my father and Kemper Goodwin had done.”

He co-chaired the fund drive to restore the building. Don Dotts, former head of the alumni association, had been listening to noted author and journalist Don Dedera (Class of ’51) grouse about how the building was ruined. The two visited then-President J. Russell Nelson and estimated it could be restored for $1 million. (A figure that proved to be woefully under budget.)

Nothing happened until Lattie Coor became president. In 1993, the alumni association needed a new home. Coor decided to kill two birds with one stone. The renovation campaign launched in 1996.

Renovation fared better than the original construction, but not by much. The budget of $3.5 million soared to $5.7 million. Much of the building had to be replaced.

The first change came about when the drop ceiling in the ballroom was removed. The stamped-tin ceiling wowed people and stirred other thoughts as well.

“The university realized we have something really significant here,” Gammage Jr. said. “There was always a risk (ASU) would have a feel of not having any history, of not having a center.”

Aside from restoring the Carson Ballroom, the balcony and stairs were replaced. A boardroom, conference rooms, a library and the alumni association offices were all added.

Ed and Nadine Carson, co-chairs of the ASU Campaign for Leadership, made the inaugural gift of $500,000. Gammage Jr. funded the conference room.

When the restoration was complete, President Coor spoke.

“There is nothing more important for a university than the history, tradition, and wisdom with which it connects its past and future,” he said. “This building reflects the longevity in which Arizona State University has helped shape our community and state. The predominance of Old Main will dignify ASU for decades to come.”

More than 300 friends and family members fill the Carson Ballroom in Old Main for the Veterans Honor Stole Ceremony on May 7, 2016. Around 100 veterans received stoles representing their branches of military service. They wore the stoles at their commencement and graduation ceremonies. Photo by Charlie Leight/ASU Now

The metaphysics of Old Main

In 2014 a grad student named Holly Lynn Fulton wrote her thesis for a Master of Arts degree: “Old Main as a Seat of Argument,” she titled it.

“Through the combined use of several elements, Old Main fulfills the crucial role of establishing its university’s legitimacy, broadcasting the school’s important role in pioneering education for central Arizona, and using the aspirations of its past to project an equally ambitious future,” Fulton wrote. “In short, Old Main acts as an ethical proof in ASU’s arguments for its upright, nuanced, and potential-rich character.”

The ancient Romans had a concept that translates as resident spirit of a place. On a campus with wildly divergent architecture, Old Main is the keeper of that identity.

“The Victorian structure is a kind of basso continuo in the composition of ASU’s self-presentation: Its presence is subtle but persistent, a driving force that reinforces the structure of ASU’s image,” Fulton wrote. “Old Main illustrates ASU’s past, which helps it act as a mode of production for ASU’s future, and allows the structure to function as a compelling symbol of the school’s established and enduring commitment to educational progress.”

The spring 2013 Army pinning ceremony on the Old Main Lawn. Photo by Charlie Leight/ASU Now

The most popular place on campus

Back to graduation week, when there can be a line to have cap-and-gown photos shot on the venerable steps. Even though, as Gammage Jr. said, “I would bet 90% of those kids never go into the building,” it provides a touchstone.

Campus tours have to cover a lot of ground, but they always stop in front of Old Main. It demonstrates to visitors that the school, Fulton wrote, “despite its heavy branding as the ‘New American University,’ has a long history in addition to its conspicuously modern amenities.”

Building manager Mike Tomah has more than 20 years of experience hosting events there. (He’s also an alum with three children attending ASU now.)

When he first started his job, all requests to book events ran through him. But so many requests poured in, the responsibility had to be spread out through the staff. Why do they choose Old Main?

“I think a lot of it is people have a connection to the building,” Tomah said. “It’s an iconic building. They have a lot of receptions. They’ll have a high-tech kind of thing down at the Union, and then they want to bring them somewhere nice, an iconic building that’s still on campus and large enough to hold their group coming down for dinner or that kind of thing.”

They’re looking for a historic feel.

“Absolutely,” he said. “And it’s one of our points of pride. … The President’s Office has done a great job of maintaining it since the restoration. … When they walk into the building, their breath is taken away. They are so amazed at how well the building is kept. … They really love the building.”

Weddings are held there, a majority of them alumni looking for a special venue.

“I think they’re looking for — you don’t want to say — a classier place to hold a reception or a dinner or an awards banquet, but that’s the feel they’re looking for,” Tomah said. “The MU (Memorial Union) does a ton of stuff, and those folks are great, but I think with our clientele here they’re looking for a really special place to do something.”

A 36-person class is being held this semester in the ballroom, the first class to be held in Old Main in decades.

Students, alumni, faculty, staff — Old Main is everyone’s building, O’Donnell pointed out.

Outstanding graduate Erika Martinez outside Old Main in November 2019. Photo by Charlie Leight/ASU Now

“As a kind of gathering place that everybody owns, it’s got more of a future than — I’m going to say Biodesign B, which you only get into if that’s your home,” he said. “Everyone else walks around it and says, ‘Oh yeah, we have wizards working in there.’ We’ll have to have spaces where wizards do their wizard stuff, no question about that. But those will be as they are now — places you walk by and go, ‘Oh that’s nice.’ But it will be the places you find yourself in control, you’re with friends and colleagues, you’re happy to be there.”

And that is Old Main.

“You’re welcome to come in here any time you want,” Tomah said.

Top photo: The Old Main dedication at Tempe Normal School of Arizona on Feb. 4, 1898. This was a gala occasion for the Normal School. Construction on the building began in 1894, but due to delays it was not completed until four years later. Photo courtesy of Hayden Archives

More Sun Devil community

'Stories of the Street' aims to humanize Phoenix's unhoused residents

When Sreevarenya Jonnalagadda first volunteered at the André House homeless shelter, she wasn’t sure how to act. “I didn’t know what to do with my legs or my hands — I was just, like,…

Stellar student finds friendship is the best algorithm

They were two retired neighbors, dogs at heel as the evening sun slanted over Hayden Lawn, watching the students in the AZ Saber club swagger and spar with glowing lightsabers. Dave Mills and…

5 years young: Mirabella at ASU keeps redefining lifelong learning

Mirabella at ASU celebrated its fifth anniversary on Jan. 22 with a progressive dinner party for its nearly 400 residents, marking how far the university-based retirement community has come since…