Agnes Smedley exhibition opens in major museum in China

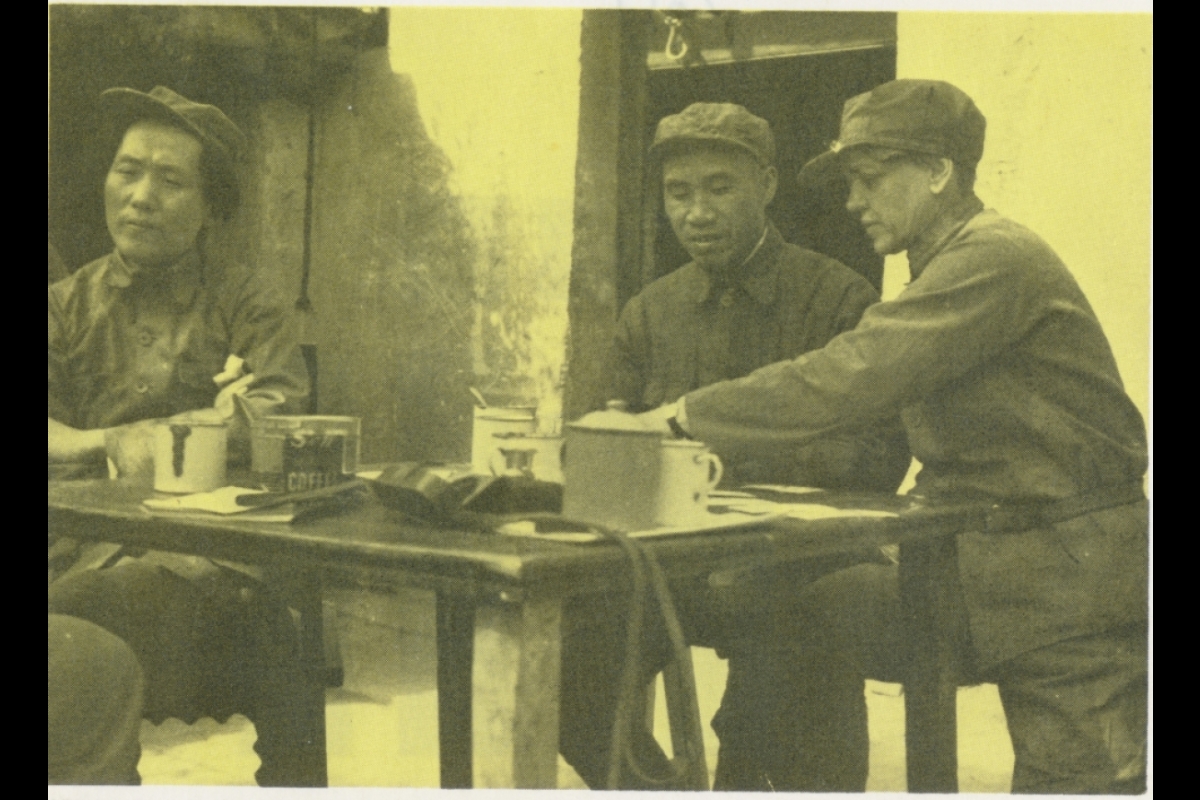

Photo courtesy of the Agnes Smedley Collection, Distinctive Collections, ASU Library

Most Americans, today, might not recognize the name Agnes Smedley.

That’s because the American journalist made a name for herself in China, where she lived and worked between 1929 and 1941, and rose to national fame as a writer of China’s revolution, deeply opposed to the anti-intellectual and authoritarian forces of that era.

Students all over China learn about Smedley in school, her extraordinary rise from poverty and her enduring ideals of equality.

Her body is buried in the Babaoshan Revolutionary Cemetery, Beijing’s central resting place for the nation’s highest-ranking government leaders and revolutionary heroes. Her headstone reads: “In memory of Agnes Smedley, American revolutionary writer and friend of the Chinese people.”

Her papers, however, are housed at Arizona State University, the place where Smedley began her life as a writer and activist, then known as the Tempe Normal College.

“Smedley was a charismatic self-made rebel from the American West, whose leftist politics resembled that of her idol, Emma Goldman,” writes Stephen MacKinnon, ASU emeritus professor of history and author with Janice MacKinnon of “Agnes Smedley: The Life and Times of an American Radical.”

MacKinnon’s research is now part of a major exhibition series traveling China, led and curated by the ASU Library, in commemoration of the 70th anniversary of Smedley’s death.

The exhibition draws largely from the MacKinnons' work and from the ASU Library’s Agnes Smedley Collection, a 46-volume archive of Smedley’s writings, photographs and other artifacts that date back to 1911.

Part of the library’s distinctive collections, the Agnes Smedley Collection comprises more than 10,000 newly digitized archival items, said ASU librarian Ralph Gabbard, affiliated faculty with the Herberger Institute for Design and the Arts.

“Before she marched with the Red Army and hobnobbed with many of China’s political elite, including Mao Tse Tung and Chou En Lai, Smedley was a student at the Tempe Normal College between 1911 and 1912,” said Gabbard, who served as the exhibition’s faculty adviser alongside its curator, ASU doctoral student Dong Huixian.

Gabbard added: “She did not have a high school diploma or the means to pay tuition, and was admitted as a ‘special student’ by the school’s then president Arthur J. Matthews.”

Characterized as “outgoing, independent and determined,” the 19-year-old Smedley quickly gained respect from her teachers and classmates at Tempe Normal while she studied and worked part time.

She was especially noted for her interest and involvement in literature and debate.

“Because Smedley came from a poor, unstable family, which she helped support from a very young age, she appeared more mature than her peers,” Gabbard said. “She saw education as an opportunity to escape the life she was born into.”

In 1912, Smedley started writing for the school’s newspaper, the Tempe Normal Student, and two months later became its editor-in-chief.

In her first editorial, Smedley suggested that the significance of education can be found in the cultivation of empathy — to help those less fortunate by providing them a platform, a voice.

She also began exploring socialist ideas.

Beginning with her days in Tempe, a series of friendships and dwellings in American cities like San Francisco and New York would provide Smedley access to a growing community of radical thinkers and social activists, including feminist Henrietta Rodman and birth control activist Margaret Sanger.

Smedley’s talent for writing and her various left-wing causes eventually would lead her to Indian freedom fighter Lala Lajpat Rai, as well as a new focus, Indian independence, which took her from New York to Germany, where she worked for several years before settling in China in 1929.

“Smedley was taken with the idea of China,” said Jim O’Donnell, university librarian and a professor in the School of Historical, Philosophical and Religious Studies, within ASU’s College of Liberal Arts and Sciences. “In 1936, she went on to Xi’an and Yan’an, where for five years she came to know and work with the leaders of the revolutionary movement that would succeed a decade later. Even though she left China in 1941, I think her burial site is a sign of where she found her true home.”

Smedley, whose history is fairly unknown to most Americans, was highly influential in ushering in the modern era of American-Chinese relations, O’Donnell said.

“This history, now gone from living memory, helps us see how the roots of our modern connections were formed by earlier generations,” he said. “We hope that this common exploration of the history of this remarkable woman will advance understanding of the way the Chinese and American people have found ways to improve mutual understanding and cooperation over the last century and will be an opportunity for study, reflection and further historical investigation on both sides of the ocean that separates us.”

“Agnes Smedley: A Revolutionary Life” opened May 1 to a steady stream of visitors at the Museum of the Former Residence of Sun Yat-sen, a major museum in Shanghai, the city where Smedley landed in the summer of 1929 as a special correspondent for the Frankfurt Zeitung.

Gabbard says the exhibition series is, in large part, thanks to the work of the ASU Library’s Timothy Provenzano, a project manager for collections care and processing, and Abigail Merritt, a preservation specialist, who digitized the collection's more than 10,000 archival items that will be accessible via the ASU Digital Repository next spring, in addition to a multidisciplinary team of students, mostly from ASU’s Herberger Institute for Design and the Arts.

The student team was led by Huixian, the exhibition’s curator and a graduate student in the School of Art.

“This exhibition is from the perspective of an American female journalist to see modern Chinese history,” Huixian said. “It might bring some fresh ideas for the young Chinese audience.”

The student team included Michael Diaz, who graduated in 2019 with his MFA from the School of Art; Kimberly Lyle, who graduated in 2018 with her MFA from the School of Art; Ni Zhan, an undergraduate student in The Design School; Dalin Yang, a computer science undergraduate student in the Ira A. Fulton Schools of Engineering; and Yipaer Aierken, a graduate student in the School of Art.

In addition to the Museum of the Former Residence of Sun Yat-sen, the ASU collaboration has led to partnerships with the Edgar and Helen Snow Center at Northwest University in Xi’an and the Edgar Snow Center at Peking University.

“On behalf of the university and the library, I am immensely grateful for the profound hospitality of our Chinese partners and the opportunity to explore this shared history,” O’Donnell said.

Due to the global pandemic, the number of people admitted to the exhibition has been limited, and the planned exhibitions for Northwest University and Peking University have also been postponed until late September and 2021, respectively.

The exhibition will eventually land at ASU.

For more information on the Agnes Smedley Collection, email Gabbard.

More Law, journalism and politics

Veteran journalists Jorge Ramos and Marty Baron talk democracy and free press

Arizona State University hosted "Truth Across Borders," a bilingual panel featuring two of America’s most iconic journalists,…

Can elections results be counted quickly yet reliably?

Election results that are released as quickly as the public demands but are reliable enough to earn wide acceptance may not…

Spring break trip to Hawaiʻi provides insight into Indigenous law

A group of Arizona State University law students spent a week in Hawaiʻi for spring break. And while they did take in some of the…