The COVID-19 pandemic has set off a cascade of troubling shockwaves.

Public officials, medical experts and others have been voicing concern about the toll the highly contagious illness is taking on our overall physical, mental and societal health.

The National Science Foundation is helping to address the potential consequences of a widespread breakdown by funding rapid-response research projects.

Among them is one titled “RAPID: COVID-19’s Impact on the Urban Environment, Behavior, and Wellbeing,” to be carried out by Arizona State University Professor Rolf Halden and associate professors Matthew Scotch and Arvind Varsani.

The NSF is providing $200,000 to get an accurate assessment of how public interventions such as social-distancing, stay-at-home sheltering and related restrictions are affecting communities.

The idea is to use the research results to guide actions for minimizing potential harm to the public from the major social and economic disruptions caused by the pandemic.

The research will focus on an unlikely data source. Halden, a professor of environmental engineering in ASU’s Ira A. Fulton Schools of Engineering and the effort’s principal investigator, will work with his collaborators to assess indicators of public health contained in community wastewater.

Wastewater testing provides picture of public health

The project draws on work guided by Halden in his role as director of the Center for Environmental Health Engineering in ASU’s Biodesign Institute.

A recent effort by Halden, Scotch and Varsani involved research funded by the National Library of Medicine, one of the National Institutes of Health, to develop a system to provide early warning signs of flu outbreaks. Other research projects focus on determining the extent of opioid misuse and the spread of the coronavirus responsible for COVID-19 in the city of Tempe, where ASU’s main campus is located.

Over the past 12 years, Halden has led research projects that have employed wastewater testing to improve and protect public health — for example, his team’s efforts contributed to the 2017 ban by the U.S. Food and Drug Administration on multiple ineffective and overused antimicrobials after Halden’s team used wastewater analytics to identify these compounds as widespread pollutants.

Since the ban, more municipalities have been added to the monitoring network at ASU known as the Human Health Observatory. The facility housed in Halden’s research center now includes wastewater testing data from more than 300 municipalities in the U.S. and more than 400 cities worldwide. In all, it provides information on the health status of more than 40 million Americans and more than a quarter-billion people internationally, including data on their behavior and exposure to toxins, viruses and the like.

What began as a tool to study harmful toxins has evolved into an early warning system for detecting both chemical and biological hazards, Halden said.

“We can measure not only the prevalence of a virus in a community, such as the new coronavirus that causes COVID-19, but we can also measure alcohol consumption, the use of stimulants, nicotine and caffeine, and track the quantities of medications people are taking,” Halden said.

The testing of wastewater and sewage sludge provides a clear look at pollutants to which the populace is being exposed and what chemicals people are ingesting and accumulating in their bodies.

“We look to wastewater as an information source to create a real-time dashboard of public health that tells us about latent threats and what needs to be done to improve a community’s health,” Halden said.

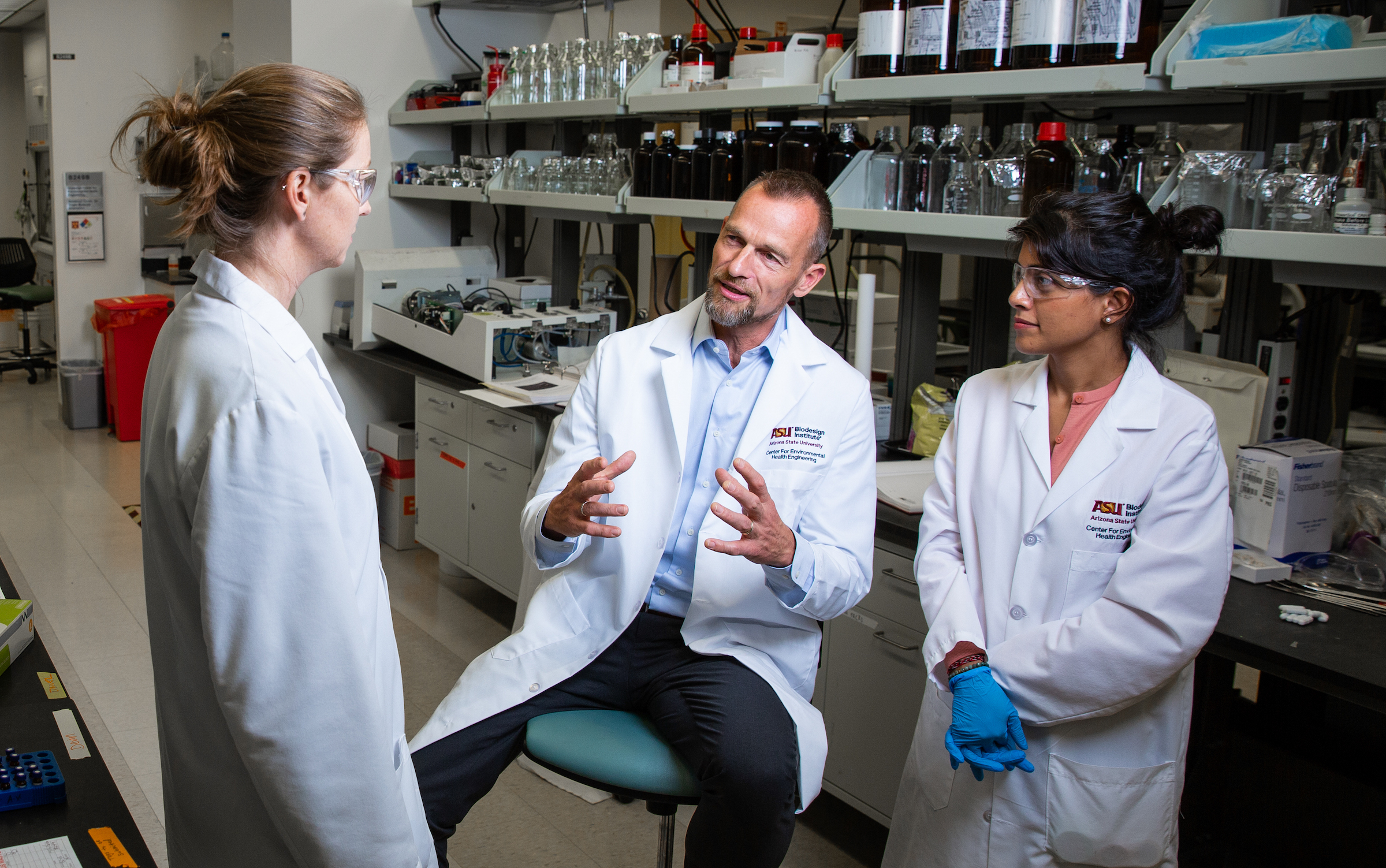

Professor Rolf Halden meets in his lab at the Center for Environmental Health Engineering at ASU’s Biodesign Institute with Assistant Research Scientist Erin Driver (at left) and civil, environmental and sustainable engineering graduate student Nivedita Biyani (at right). Driver and Biyani are among faculty members and students on Halden’s team conducting research to help develop responses to the effects of the COVID-19 pandemic on public health. Photo by Deanna Dent/ASU Now

Uncovering threats to public health

Decades of compiling such data produced a collection wastewater and municipal sludge samples from hundreds of cities. The samples have been analyzed for chemical and biological markers of human health conditions and archived in the Human Health Observatory, which is a shared resource available to the international research community.

That inventory of samples has yielded insights into human exposure to pesticides, the identification of chemical threats that foster resistance to medicinal drugs and antibiotics, and the discovery of hundreds of novel viruses that could potentially pose a danger to human health.

Through the knowledge accessible in this vast archive, and by applying medical diagnostic techniques to wastewater analysis, Halden said, “We ultimately are aiming to prevent diseases before they can develop into clusters of morbidity or full-blown epidemics and deadly pandemics.”

For more than two years, Halden’s research team has been working with the Tempe government to analyze the city’s wastewater to get a clearer indication of the levels of opioid use in various communities.

The types of various licit and illicit drugs and their consumption over time can be viewed by the public on an interactive opioid dashboard that includes data going back to May 2018. Since October 2019, the researchers have also been examining the wastewater for viral threats. As a result of the project in Tempe, the team recently completed the world’s first online COVID-19 dashboard, which displays levels of the new coronavirus, SARS-CoV-2, in the wastewater of an entire city at the neighborhood level.

Gathering bio-intelligence to protect community

Those projects have given city officials reliable information for data-driven decision-making to guide policy and action plans in response to both public health challenges, the opioid epidemic and COVID-19, said Rosa Inchausti, director of Tempe’s Strategic Management and Diversity office.

The city is planning to allow many of its businesses to re-open in June and is easing restrictions on public gatherings enacted to curb the spread of COVID-19. The wastewater testing data will help shape the specifics of what prohibitions will be lifted and to what extent, Inchausti said.

The data also are useful in developing public education to explain the reasons behind city leaders' decisions on the reopening strategies, she added.

Tempe officials look at the researchers work “as gathering bio-intelligence about local public health that helps people understand that what we are doing is to protect them and their families,” Inchausti said.

City leaders don’t view the opioid and COVID-19 projects as one-time efforts, she said, but as the start of an ongoing public health monitoring infrastructure that will enable rapid responses to current and future problems.

The NSF views this method for analysis of wastewater and municipal sewage sludge as an effective, inexpensive and rapid approach for public health assessment and threat detection.

From a broader perspective, the agency also sees the method as a valuable resource for helping communities build resilience against the psychological and sociological challenges posed by the COVID-19 crisis.

Preparing to cope with emotional strain of COVID-19

Information derived from the research is to be paired with U.S. Census Bureau data on demographics and population figures and used as a foundation for evidence-based crisis management and decision-making by government leaders and other policymakers, as well as by scientists, health care providers and social service agencies.

Plans are to make data on additional wastewater-borne biomarkers available to community leaders and to the public through an online platform for emergency response.

Halden said those findings can help communities better deal with the debilitating behavioral and emotional ramifications of the COVID-19 pandemic.

Halden’s co-investigators for the project will play an important role in ensuring research results are based on sound science.

Scotch, the assistant director of Halden’s research center, is an associate professor of biomedical informatics in ASU’s College of Health Solutions. His expertise includes applying molecular and genomic epidemiology to the study of viruses, with a focus on influenza. He will oversee the design, development and management of the data warehouse for the project, as well as analysis of biomarker panels, which are used to diagnose diseases and determine their different stages within patients.

Varsani is a molecular virologist and associate professor in ASU’s School of Life Sciences. His expertise is in viral detection, evolution and metagenomics, the study of genetic material recovered directly from the environmental samples. Varsani will provide his expertise in viral epidemiology, the study of the occurrence and spread of viruses and the factors involved in their growth, development and transmission.

Wastewater monitoring efforts lead to entrepreneurial ventures and global engagement

The still-growing research team also includes Erin Driver, who earned a master’s degree and a doctoral degree in civil, environmental and sustainable engineering in the Fulton Schools and is now an assistant research scientist in Halden’s lab. Driver is leading the Tempe wastewater sampling efforts and has joined other current and former lab members to bring wastewater testing to communities and industries across the U.S. through an ASU-based startup company, AquaVitas LLC.

In addition, two doctoral students in Halden’s lab, Devin Bowes and Nivedita Biyani, have cofounded OneWaterOneHealth, a nonprofit project supported by the ASU Foundation to bring wastewater testing to underserved, at-risk communities in the U.S.

Bowes and Biyani helped to secure funding from the J.M. Kaplan Fund and the Arizona-based Flinn Foundation to make wastewater analytics an equitable resource from which all communities can benefit.

Halden emphasized that monitoring for SARS-CoV-2 in wastewater is not restricted to the U.S. or to the work of researchers in his lab. Previously established collaborations are continuing around the globe, including in Mexico, the United Kingdom and Ireland, as well as in China and Australia.

For more on this topic, listen to the webcast “Sewage Testing as a COVID-19 Hot Spot Tracker” with Rolf Halden and Devin Bowes, from Earth Institute Live at Columbia University.

Top photo: A wastewater plant. Credit: Shutterstock

More Science and technology

Science meets play: ASU researcher makes developmental science hands-on for families

On a Friday morning at the Edna Vihel Arts Center in Tempe, toddlers dip paint brushes into bright colors, decorating paper fish. Nearby, children chase bubbles and move to music, while…

ASU water polo player defends the goal — and our data

Marie Rudasics is the last line of defense.Six players advance across the pool with a single objective in mind: making sure that yellow hydrogrip ball finds its way into the net. Rudasics, goalkeeper…

Diagnosing data corruption

You are in your doctor’s office for your annual physical and you notice the change. This year, your doctor no longer has your health history in five-inch stack of paperwork fastened together with…