“Never in the field of human conflict was so much owed by so many to so few,” said Winston Churchill in August 1940, a few months after becoming prime minister of the United Kingdom as World War II raged on with terrifying force.

It’s a phrase with particular resonance in our current moment, as many of us make small personal sacrifices — like staying home — in order to try to lessen the blow of the pandemic on our front-line workers, who have made such enormous sacrifices for so many.

We find ourselves reaching for these sorts of analogies, historical examples of crises, because we seek narratives of overcoming, of resolution. Although the analogy between our current crisis and war is imperfect, said Andrés Martinez, a professor of practice at Arizona State University's Walter Cronkite School of Journalism and Mass Communication and and the editorial director of Future Tense, there are unquestionable similarities in “the need for leadership to mobilize society to meet the crisis at hand.”

On Tuesday, Martinez discussed leadership in times of crisis — and what we might learn from Churchill’s example — with Erik Larson, author of "The Splendid and the Vile: A Saga of Churchill, Family, and Defiance During the Blitz."

The discussion was the most recent installment in Future Tense’s biweekly Social-Distancing Social series, which has addressed topics from the impact of the pandemic in prisons and jails to the future of the U.S.-China relationship — and even the lessons our pets can teach us in this moment. Future Tense, a “citizen’s guide to the future,” is a collaboration between ASU, New America and Slate magazine.

Churchill’s wartime leadership might seem an improbable subject for Future Tense, but Martinez said Larson’s tale, more than those penned by other Churchill biographers, highlighted the prime minister’s obsession with technology and science, and consequent empowerment of scientists like Frederick Lindemann, aka "The Prof.”

Moreover, Martinez joked at the outset of the discussion, “Churchill, in your account, comes across as someone who truly mastered the art of working from home.”

The prime minister frequently worked from his bed, armed with a cigar, a tumbler full of water and whiskey, and his personal typist nearby.

“If I were Winston Churchill and I was doing this Zoom interview with you right now, I would be in the bathtub,” Larson said.

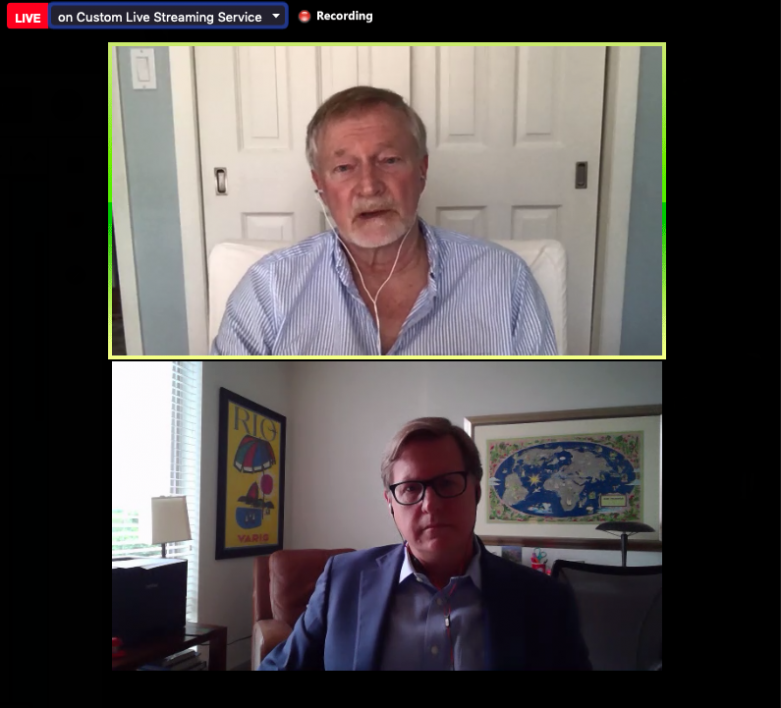

Author Erik Larson (top) discusses leadership in times of crises with Andrés Martinez, ASU professor of practice at the Cronkite School and the editorial director of Future Tense. The talk was part of Future Tense’s biweekly Social-Distancing Social series.

Larson is the author of eight books, including "The Devil in the White City," "Dead Wake: The Last Crossing of the Lusitania" and "In the Garden of Beasts." Larson compellingly reconstructs historical events from different, detail-rich perspectives, bringing readers back in time and then leaving them to ruminate on the present.

The inspiration for "The Splendid and the Vile," said Larson, came when he moved with his wife from Seattle to Manhattan.

“I had this kind of epiphany about what 9/11 had been like for New Yorkers versus what the rest of us had perhaps watched in real time ... the sense of violation of having your home city attacked,” he said. This feeling drew him to write about what it had been like for Londoners to endure the German Luftwaffe’s bombing campaign that lasted 57 consecutive nights.

Larson was interested in the “day-to-day experience,” how people endured terror, lived through it. At first, he wanted to write about a typical London family, but later he turned to the “quintessential London family:” Churchill’s.

One of the key pieces in Larson’s research was the Mass Observation Archive, a collection of diaries written by British citizens reflecting on everyday life. The project started shortly before the war, but the diarists continued their work after the fighting broke out, constructing a unique and intriguing record that details the everyday realities of life during unprecedented crisis.

Author Erik Larson

Larson also relied heavily on the diary of Churchill’s daughter Mary, who was 17 when her father became prime minister. Larson is one of two scholars who has been able to consult the diary, which provides yet another window into the everyday, its tragedies inseparable from its small joys, humor and love.

Churchill is often praised for his excellence in communicating “a sense of reason for courage,” as Larson put it. But the thing that made Churchill a great orator, said Larson, was not only his ability to turn a phrase but also the structure of his speeches, his ability to soberly appraise a situation, follow with “real grounds for optimism,” and finally “place people into the grand epic of British history.” He understood the importance of symbolic acts, said Larson.

Churchill, of course, is a nuanced character and a deeply flawed one. Even in his time (certainly before the outbreak of war in 1939), he was perceived to be a somewhat bombastic character from a previous age, and his Victorian enthusiasm for imperialism would be a source of tension with his American allies and significant swaths of the British public in the postwar era.

Larson’s book chronicles Churchill’s critical first year in office (as lived by engrossing characters in his orbit), but its last chapter movingly recounts his final days in office, as the British public voted him out — “ironically,” Larson writes — just two months after Hitler’s defeat. This begs the question, Larson noted, whether people look for different types of leaders during existential crises. Voters had an intense connection with Churchill in wartime, but had a sense he wasn’t the right person to see them through the postwar rebuilding.

What is clear, said Larson, is that empathy was Churchill’s secret ingredient to connect with his people when they most needed inspiration.

“To be an effective leader you have to have a strong, well-balanced moral compass,” Larson said. “And one ancillary effect of having a strong moral compass is that you also are able to experience and express empathy.”

Register for upcoming Future Tense events and read Future Tense commentary. Watch a recording of this event.

Written by Mia Armstrong

Top image courtesy of Pixabay

More Law, journalism and politics

Veteran journalists Jorge Ramos and Marty Baron talk democracy and free press

Arizona State University hosted "Truth Across Borders," a bilingual panel featuring two of America’s most iconic journalists, last week in the Evelyn Smith Music Theatre on Arizona State University's…

Can elections results be counted quickly yet reliably?

Election results that are released as quickly as the public demands but are reliable enough to earn wide acceptance may not always be possible.At least that's what a bipartisan panel of elections…

Spring break trip to Hawaiʻi provides insight into Indigenous law

A group of Arizona State University law students spent a week in Hawaiʻi for spring break. And while they did take in some of the sites, sounds and tastes of the tropical destination, the trip…