“Take a risk: We can’t forget the future,” says Dr. Fong, a central character in “Paciente Cero,” a short story authored by renowned Mexican writer Juan Villoro for Future Tense Fiction, a collaborative storytelling project from ASU, Slate magazine and New America.

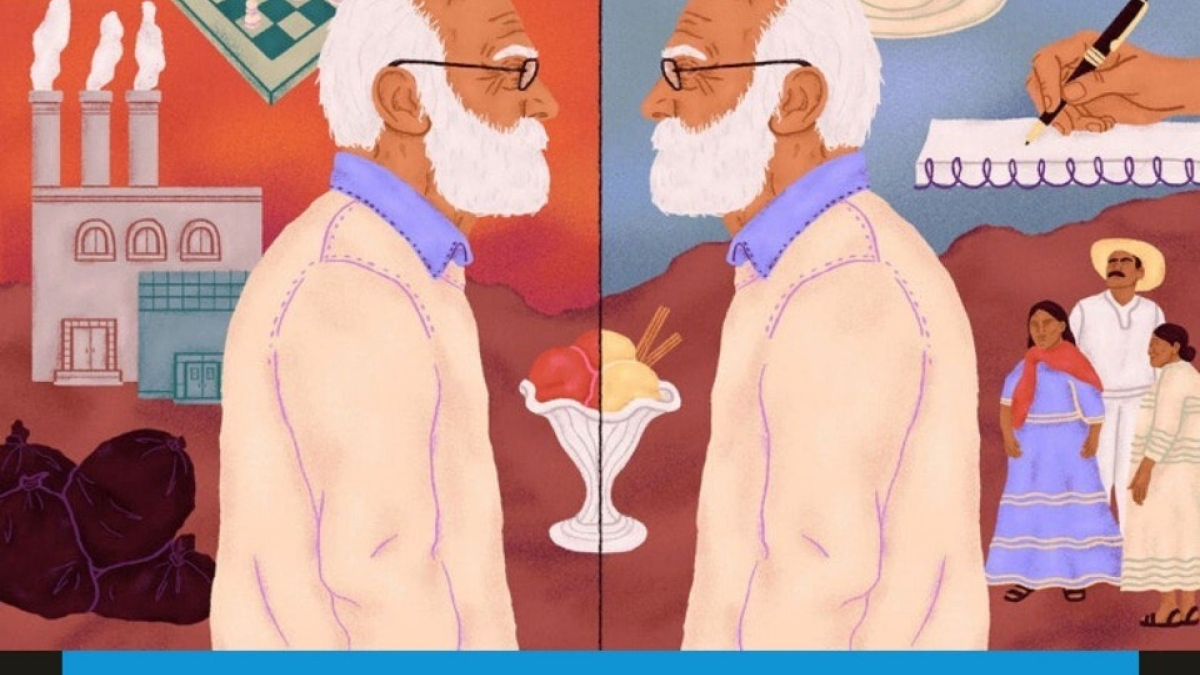

The story lyrically describes a future in which Mexico — at the behest of China and with the help of a populist leader — has been transformed into a giant recycling plant for U.S. waste. It explores mind control, authoritarianism, bio-surveillance, the resilience of indigenous cultures, and, ultimately, “the disorder of the truth.”

Andrés Martinez, the editorial director of Future Tense and a professor of practice at the Cronkite School who oversees ASU’s Convergence Lab events in Mexico City, first met Villoro in the fall of 2018, when the Universidad Nacional Autónoma de México invited the writer to moderate an event on the 50th anniversary of the Mexico City Olympics co-hosted with ASU’s Global Sport Institute. Martinez subsequently invited the author — with fingers crossed, he admits — to write a story for Future Tense Fiction.

The result was “Paciente Cero,” published last month on Slate, and simultaneously in Spanish in Mexico’s prestigious Letras Libres magazine, a publishing partner of Future Tense.

On Wednesday, Villoro, currently a visiting professor at Stanford’s Center for Latin American Studies, discussed the story — as well as how our imaginations shape our realities — in a Convergence Lab webinar with Ed Finn, director of ASU’s Center for Science and the Imagination and co-editor of Future Tense Fiction. The webinar was moderated by Martinez.

Author Juan Villoro (bottom) discusses his "Paciente Cero" story with Andrés Martinez (top left) and Ed Finn, during an ASU Convergence Lab webinar held April 15. Image courtesy Mia Armstrong

The Center for Science and the Imagination was born out of a need to reimagine our relationship with the future, recognizing that “stories are the building blocks we use to make the future happen,” Finn said, an idea which dovetails with the plot of Villoro’s story.

The center's mission and the Future Tense Fiction project seek to counter, at least in part, the dominance of dystopian narratives about the future with narratives that make room to imagine progress, or what Finn calls “thoughtful optimism.” This doesn’t imply walking around with rose-colored glasses, but it does call on us to imagine a more complex relationship with the future.

“When we tell stories, we are trying to convey new possibilities,” Villoro said.

We must not only put to paper our fears for the future, but also our hopes, he said, “inventing, at the same time, possibilities of resistance and of well-being.”

The question to ask is, “How are we going to feel better in the future?”

This question is met with a complex answer in “Paciente Cero,” in which, Villoro explained, “the algorithm of inconformity has disappeared” through social control technologies leveraged by an authoritarian regime. This, he said, presents grand problems for the characters in this imagined future.

“Error has been the great stimulus of the human species,” he said. “He who dares to think in a different way is capable of imagining.”

The story is riddled with symbolism that opens doors into complex narratives about Mexico’s past and present, and the coexistence of tenses in millennial civilizations. There is the basketball court “presented as the ‘playground of the world’” that harkens back to the ball games played by precolonial indigenous civilizations, the baseball cap “promoting a vanished political party,” and the vanilla ice cream turned from yellow to red.

“It’s important to understand that in everyday spaces we can find a door to the past,” Villoro said. In Mexico, these doors often open to deep passages with “very important solutions for the future,” he noted.

The story is also a story of love, Villoro said, itself a sort of “inheritance” for the 91-year-old narrator’s partner, Ling, who, the story’s narrator explains, “accompanies me with the shifting constancy of the phases of the moon ... Our lives crossed like two contrails in the sky. I’ve been captivated by this phenomenon multiple times: One white slipstream begins to dissolve overhead as another passes through it, giving it new meaning.”

The lesson of this element of the story is a big one. “To make mistakes,” Villoro said, “has to do with the art of love.”

The story, which features an autocratic populist leader — the “Founding Hero” who “has been governing so long it’s no longer worth tracking the time” and who calls his enemies “reckless,” “irrelevant,” “lunatics,” “egomaniacs,” and “chancers” — could be interpreted as a critique of several contemporary leaders. But it’s also a sort of self-critique, Villoro said.

As writers, we often help those leaders advance a certain narrative of themselves and their visions for the future, becoming “accomplices” in the “construction of a parallel reality” of unchecked power.

“One of the lessons of the human experience is that you cannot address the future if you don’t have a sense of the past and a feel of the present,” Villoro said. “This intermingling of tenses is, I think, the most rewarding thing of literature. I think that any writer that tries to invent new worlds is also trying to convey a mirror of his own world and his own present.”

In our own present, facing a pandemic that we can’t yet see the end of, imagination of the type presented in “Paciente Cero” is crucial.

It is through this sort of imagination, Finn explained, that “we escape the island of individual consciousness” and come to place ourselves in others’ circumstances, developing empathy. Our present moment should also remind us of “the importance of speaking for the future,” Finn said.

Our most significant task in all this, according to Villoro, is “to invent the common sense of the future.”

It is something we’re better off inventing together.

Written by Mia Armstrong

More Arts, humanities and education

ASU professor's project helps students learn complex topics

One of Arizona State University’s top professors is using her signature research project to improve how college students learn science, technology, engineering, math and medicine.Micki Chi, who is a…

Award-winning playwright shares her scriptwriting process with ASU students

Actions speak louder than words. That’s why award-winning playwright Y York is workshopping her latest play, "Becoming Awesome," with actors at Arizona State University this week. “I want…

Exceeding great expectations in downtown Mesa

Anyone visiting downtown Mesa over the past couple of years has a lot to rave about: The bevy of restaurants, unique local shops, entertainment venues and inviting spaces that beg for attention from…