Long before IBM, Apple and Google set up shop in Silicon Valley, the area was home to government-funded research operations that developed electronics and communications devices. While it is now known as a global epicenter of technology, only some of the economic development came about through the muscle of venture capital; the rest came from government funding. Several U.S. cities, from Denver and Seattle to Washington, D.C., have similarly built upon government investment in universities to build thriving economies.

The Phoenix metro area has emerged as a global hotbed of innovation that can become a new type of Silicon Valley — with continued investment, analysts say. A key part of creating a resilient economy relies on the current ASU partnerships with industry in areas such as medical tech, wearables, advanced manufacturing, sustainability and communications. Through innovation centers, the university is supporting research, helping to bring new products to market and driving entrepreneurship and industries that benefit the entire state.

Arizona is home to thousands of tech companies, and a report by the National Academy of Inventors ranked ASU in the top 10 universities for patents awarded worldwide in 2018, the most recent year for which rankings have been released. With a top engineering talent base, an established tech sector and a thriving startup scene, economic developers and analysts say it’s now time for the region to double down and create a future in new disruptive industries.

While Phoenix has many key components to develop a new innovation economy, it also needs state government investment, in addition to incoming federal government grants and private funding, to create in a “big and thoughtful way,” says Inc. columnist Dustin McKissen.

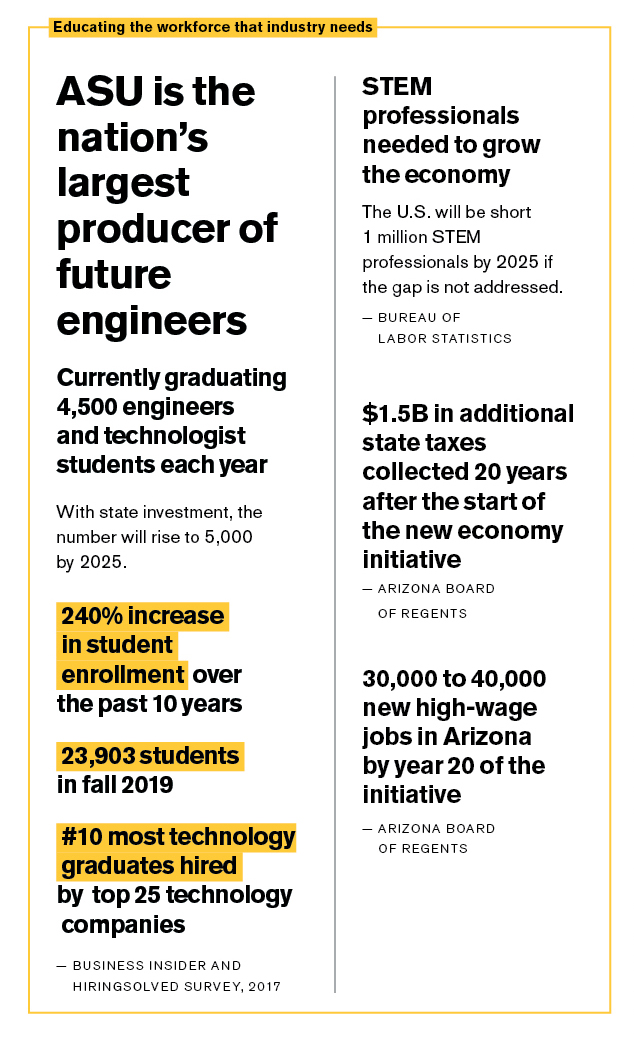

To that end, the Arizona Board of Regents is requesting state funding for a new economy initiative, including $46 million for ASU in fiscal year 2021 to enable the state’s transformation by preparing the workforce and making metro Phoenix the leading U.S. producer of engineering talent. Part of the plan is to better fund K-12, and to increase access to higher education across the state, including in rural areas, as well as to improve high school completion and college attendance rates. Another focus is the creation of additional innovation centers that leverage university expertise to solve industry-identified problems.

Students participate in Devils Invent, where they design and build solutions to real-world problems submitted by the community and industry. Erika Gronek/ASU

In Silicon Valley, it was ultimately government funding and public policy that fueled development, said Margaret O’Mara, author of “The Code: Silicon Valley and the Remaking of America” and history professor at the University of Washington.

Until the 1940s, the California valley was largely agricultural. With an influx of federal funds to support Cold War electronics, Stanford University focused its curriculum on sciences and engineering to support federal research labs developing new communication devices, O’Mara said. Such government backing eventually helped to pave the way for Intel, AMD, NVIDIA and an entire new economy. In 1971, a journalist dubbed it “Silicon Valley USA.”

Government support can often provide the boost that industry and researchers need to bring distant ideas to market. “[These] are things that the market is not going to do by itself,” O’Mara said.

O’Mara writes that government investment “flowed ... in ways that gave the men and women of the tech world remarkable freedom to define what the future might look like, to push the boundaries of the technologically possible, and to make money in the process.” That, coupled with tech-friendly tax regulations and business-friendly policies, all helped Silicon Valley grow large, writes O’Mara.

Creating a resilient economy

With an already established legacy of mainstay semiconductor companies and talent and business-friendly laws, the Phoenix metro area and Arizona are thriving in areas like medical tech, the internet of things, sensor-enabled technologies and manufacturing and are poised for additional growth, said Chris Camacho, president and CEO of the Greater Phoenix Economic Council.

“By fostering an environment that promotes entrepreneurial thinking and innovation at scale, we have made significant progress in areas that include additive manufacturing, solar energy and wearable technologies, among others,” said Kyle Squires, dean of the Ira A. Fulton Schools of Engineering at ASU. “With an investment to help establish science and technology centers where faculty, students and industry collaborators can grow ideas, share resources and provide advanced training, the Fulton Schools will be primed to catalyze the tech ecosystem in the Phoenix metropolitan area and help launch companies that will drive future industries.”

Public-private partnerships

Using a mix of private money, grants from the National Science Foundation and the U.S. Department of Defense’s Defense Advanced Research Projects Agency (DARPA) and other national government agencies, along with venture capital, ASU is participating in the establishment of various public-private partnership centers that help local companies get new products onto the market faster. These centers, and the new economy they can help create, not only benefit engineers but can also lead to a diverse range of jobs to benefit all Arizonans.

“Hubs of innovation and talent generation will feed the local companies and draw others in,” explains industry partner Hans Stork, senior vice president of research and development at ON Semiconductor, a global semiconductor supplier based in Phoenix. “This in turn drives the economy and spurs further reinvestment.”

The best prospects are those areas where there is an opportunity to build something new, and where industry partners are willing to participate, said Gregory Raupp, director of the MacroTechnology Works Initiative and research director of the WearTech Applied Research Center.

In September 2019, the WearTech Applied Research Center opened as a joint venture between the Fulton Schools and the Partnership for Economic Innovation, a collective dedicated to expanding economic potential in Phoenix.

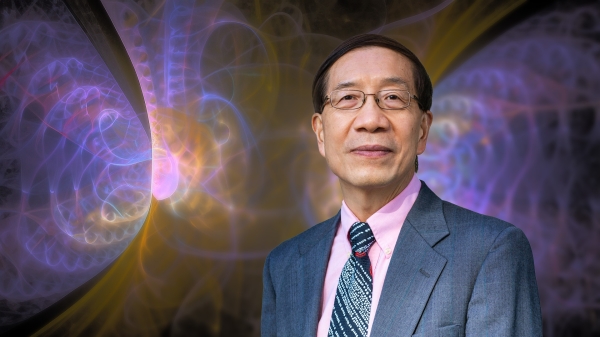

Associate Professor Dan Bliss, along with students and other researchers, is working on making tech in our devices less expensive, more energy efficient and more powerful. Marco-Alexis Chaira/ASU

Another promising area is in communications. Dan Bliss, ASU associate professor and director of the Center for Wireless Information Systems and Computational Architectures, his team and industry partners are striving to improve wireless communications for personal, machine and internet of things systems by creating more sophisticated protocols and computation engines. “We are actively pursuing the commercialization of multiple pieces of this technology,” Bliss said.

While many of us are still using mobile phones on the 4G network and anticipating 5G, George Trichopolous and Ahmed Alkhateeb, assistant professors of electrical engineering in the Fulton Schools, are preparing for the implementation of 6G by 2030. By exploring the capabilities of wireless signals in the unused range above 100 GHz, they believe they can demonstrate innovative 6G use cases, such as better enabling internet of things devices.

At the Manufacturing Research and Innovation Hub at The Polytechnic School, Dhruv Bhate conducts research on additive manufacturing, including how 3D-printed metal parts may be used in aircraft to save space, time and money. Through America Makes, a collaborative organization that supports additive manufacturing technology, the lab is testing how such parts may be able to withstand extreme loads and temperatures for NASA and the Department of Defense.

“There are many questions that have to be answered before that technology can be inserted in the product,” Bhate said. “A big role the state can play is in providing the funding that creates an ecosystem where [industry and academia] bring something to the table and we work on relevant problems.”

With a $1.75 million grant from the NSF, ASU engineers and other experts are striving to make electrical grids smarter and safer by reducing data losses, outages and cybersecurity threats.

“We need electric power systems to have as much accurate real-time data analytics as possible,” said Lalitha Sankar, associate professor of electrical, computer and energy engineering in the Fulton Schools. “We don’t want to be doing forensics that determine the cause of problems only from gathering evidence after the fact. We want to see patterns in the data that help predict what’s starting to happen on a grid. We also need to visualize these patterns to the operator succinctly and meaningfully to further aid the operator in distinguishing between normal and abnormal operations.”

Instead of trying to compete in a market of ordinary, mass-produced electronics, working hand-in-hand with industry can help identify new high-value technologies that researchers can bring to market, Raupp said.

“If we can focus around the idea of a versatile, agile manufacturing with rapid technology development and platforms that can be built on quickly creating the next version of whatever we need … that’s the kind of idea we want to create,” Raupp said.

Funding and fueling the silicon desert

Continued growth of the Phoenix area’s innovation economy depends on the ability to maintain a highly educated and trained workforce. In addition to technology jobs, these new industries will also help to create mid-level jobs in sales, retail and production, along with professional, managerial and cybersecurity jobs.

It’s important to continue building, Bliss says, because disruptive technologies and groundbreaking innovation can take years of R&D before coming to market. And while ASU graduates more than 4,500 engineers and technologists per year, that isn’t enough to support existing companies, and not enough to help build the new emerging economy.

“People underestimate how long it takes to move technology to market, because they only see the last 2%. If you open up your phone, there are 50 years of research that went into that,” Bliss said.

Such long-term investments can yield an impressive return for the state. If new business opportunities increase by as little as 10%, the 10-year state and local fiscal impact will grow by another $700 million with 25,000 new jobs created, according to the Arizona Board of Regents.

In addition to training the workforce for tomorrow’s opportunities, many of ASU’s students, graduate students and postdoctorates will likely go on to form new startups. Raupp is personally working with seven startups around medical technology, half of which were based upon ASU technology and spinoffs. “We’re providing the talent that can go into these startups, but we’re also teaching and training people to be entrepreneurs,” Raupp said.

Camacho believes the state is in the midst of a historic economic transition that will not only attract new capital in these sectors but also give birth to more homegrown companies and potentially make Phoenix the next Silicon Valley.

“Just in the past decade we’ve seen massive amounts of entrepreneurial activity and that will continue to compound over the next 20 years," Camacho said. "I am extraordinarily optimistic about the future of our region and state.”

Written by Craig Guillot, a business journalist whose work has appeared in The Wall Street Journal, Forbes, Chief Executive magazine and Entrepreneur. This story originally appeared in the spring 2020 issue of ASU Thrive magazine.

Top photo: ASU faculty and students are working with industry partners to solve problems, such as helping to make the electrical grid safer and more robust, advancing the 3D printing of metals, improving solar tech, driving new manufacturing technologies — and more. Photos by Erika Gronek and Kessica Slater/ASU

More Science and technology

Extreme HGTV: Students to learn how to design habitats for living, working in space

Architecture students at Arizona State University already learn how to design spaces for many kinds of environments, and now they can tackle one of the biggest habitat challenges — space architecture…

Human brains teach AI new skills

Artificial intelligence, or AI, is rapidly advancing, but it hasn’t yet outpaced human intelligence. Our brains’ capacity for adaptability and imagination has allowed us to overcome challenges and…

Doctoral students cruise into roles as computer engineering innovators

Raha Moraffah is grateful for her experiences as a doctoral student in the School of Computing and Augmented Intelligence, part of the Ira A. Fulton Schools of Engineering at Arizona State University…