Perceived gender inequity in sport

Young women drop out of athletics by the age of 14 at a rate two times higher than boys. Photo courtesy of hippopx.com

Worldwide, more girls than ever before are participating in organized sport.

As a result, they see immediate positive effects on their self-esteem and body image and have reduced risks of drug abuse, teen pregnancy, depression and eating disorders.

Yet despite these benefits, fewer girls participate in sports than their male peers. In fact, young women drop out of athletics by the age of 14 at a rate two times higher than boys.

The reasons are varied, according to Arizona State University Hugh Downs School of Human Communication Assistant Professor Alaina Zanin.

Zanin and her research team were awarded an $18,000 seed grant from the ASU Global Sport Institute to find out why these gender disparities in youth sport participation exist. Their research won a top paper award at the National Communication Association annual convention in 2019 and was recently published in the academic journal Communication and Sport.

The team found that there are fewer girls playing sports due to lack of access, safety, funding and transportation.

They also found that the situation is more pronounced for young women in underserved communities and young women of color. The groups have less access to athletic programs and engage in less physical activity.

Zanin says there is also a gender bias, in that girls are more likely to be expected to help around the house or take care of younger siblings. “It’s more acceptable for the boys to participate in sport.”

The research team found the dropout rate is also influenced by messages young women receive about playing sports from their peers, parents, athletic heroes and the media, and how they identify with those messages.

“There are stereotypical attributes to athletes, such as strength and power that often conflict with socially constructed feminine attributes, such as weakness, frailty and submissiveness,” Zanin said. “Some young women don’t think they can be both feminine and athletic.”

As part of a larger study to better understand how young girls think about athletics and femininity, Zanin and her team created two run-club programs for girls between the ages of 8 to 12 at two elementary schools in the Southwest.

At one site, 13 girls enrolled at the beginning of the season, but only six finished.

“This speaks to the barriers that some of the girls faced," Zanin said. "They had transportation issues, or they would switch schools and had to leave the program.”

At the other site, all nine girls completed the entire run-club program.

When the run-club program ended, the research team conducted interviews with 13 girls who participated in the run-club, as well as 12 girls who did not participate in any sports to better understand how girls reconcile the idea of being both athletic and feminine.

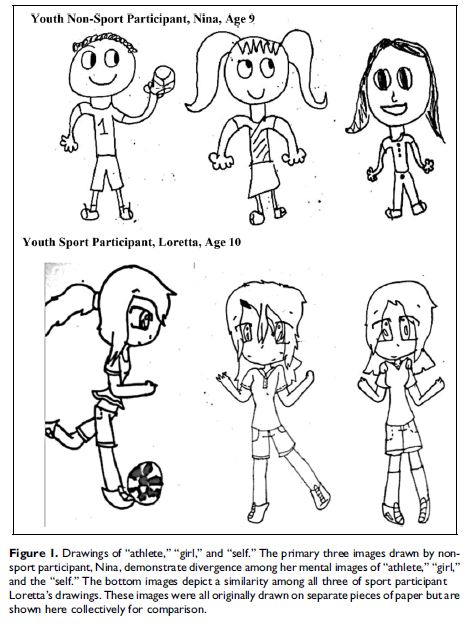

The researchers asked all the girls to draw three pictures: an athlete, a girl and a picture of themselves. The research team then analyzed the drawings to determine similarities and differences among the two groups of girls — the girls that participated in the run-club — and the girls that did not participate in sport.

“We wanted to know, what were their mental models of what it means to be an athlete?” Zanin said. “We found significant differences between those two groups.”

The contents of the drawings were analyzed for gender, sports activity, dress, makeup, hairstyle and whether they drew a real person, such as a parent or a friend, or a generic person.

The nonsports participants were much more likely to draw boys as athletes than sports participants, while the girls who participated in sports all drew girl athletes. They also found girls who participated in sport were more likely to draw themselves engaged in athletic activity, whereas nonsport participants were more likely to draw themselves not engaged in any activity.

“What our study shows is that when girls are exposed to sport, their idea of who belongs in sport changes,” Zanin said. “As a result, we can’t expect them to take on these identities before they are able to try them out.”

Infographic courtesy of Alaina Zanin.

“If you ask a child who has never been exposed to sport, ‘Are you an athlete?’ they’ll say ‘No, I’m not an athlete,’ because they’ve never enacted that identity. But if you ask a girl in a run-club if she’s an athlete she'll say, ‘Yes, I am a runner, I am an athlete,’ only because they’ve been invited.”

Zanin concludes that we need to create structures that allow girls to have access to sport earlier instead of assuming that they aren’t interested. “We often hear that girls don’t want to play a sport, or that organizers can’t fill a team, which is just not the case.”

Zanin adds that we need to reduce barriers for parents and address transportation issues.

“We also need more stakeholders who are interested in helping children reach their full potential, including nonprofit organizations, public schools, parents and parent groups,” she said.

She says more women coaches are also needed so that girls can see women as both feminine and athletic, rather than one or the other.

The benefits of youth sport last a lifetime

“Participation in youth sports has a sleeper effect,” Zanin said. “Women who have participated in youth sport are more likely to have increased physical activity and higher self-esteem later in life. They are also more likely to hold leadership positions, are able to better manage conflict and are more resilient.”

Recently, Zanin and her colleagues, ASU Professor Vera Lopez of the School of Social Transformation and ASU Assistant Research Professor Allison Ross of the School of Community Resources and Development, won an additional $15,000 seed grant from the Global Sport Institute to develop an empowerment coaching course at ASU that will train students as coaches for new youth sports sites in underserved communities in Maricopa County. The Hugh Downs School gave the team matching funds of $5,000.

“I’m very excited about this next phase of my research because it really is an exponential process of growing empowered women as leaders,” Zanin said. “We’re trying to empower students, particularly students who are women of color to go into underserved communities and become role models for these girls to show them that they can be athletes, they can go to college, they can be leaders, and they can use their voices to make an impact in their community.”

Zanin added, “Long-term, you’re developing empowered women, which is a pipeline of empowerment if you will, and that is really important if we are going to make large scale change for women.”

“They are going to be more empowered to run for office, to sit at the boardroom table, to start their own business," Zanin said. "You can see immediate benefits as well as long-term benefits. That's my hope for this project.”

“The research performed by Professor Zanin and her team typifies much of the socially embedded work done here at the Hugh Downs School,” said Linda Lederman, professor and director of the school. “Here we have a researcher who is partnering with community members in such a way that when the researcher leaves, the community members are more empowered to continue their work.”