ASU Law’s Academy for Justice tackles reentry for its inaugural event

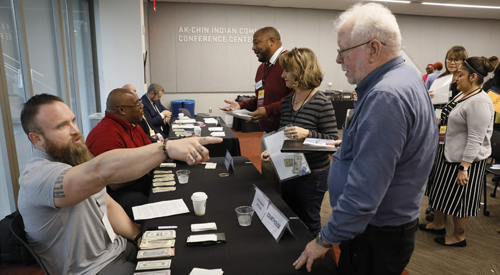

The summit launched with a reentry simulation — run by Tasha Aikens (left), a reentry specialist with the U.S. Department of Justice — in which participants played the role of just-released inmates.

The Sandra Day O’Connor College of Law at Arizona State University created its Academy for Justice in 2016 to help improve the criminal justice system by bridging the gap between academia and on-the-ground reform efforts.

The academy took a big first step in bridging that gap by producing and distributing a comprehensive four-volume set of criminal justice reform issues and policy recommendations, authored by some of the nation’s foremost legal and criminal justice scholars.

The academy is now taking the next steps, bringing various criminal justice stakeholders together to work toward solutions. In December, it hosted a daylong summit on one of the most critical issues plaguing the criminal justice system: reentry. Specifically, the vast number of imposing challenges that incarcerated individuals face as they try to rejoin society after serving their sentences.

Executive Director Dawn Walton said she and the academy’s founder, Faculty Director Erik Luna, have been gathering feedback from those involved with criminal justice reform, and it was those conversations that gave rise to the summit.

“It started off with Erik and I going on a listening tour,” she said. “Once I came on board, we spoke with individuals in the community, different reform groups, different government agencies and people who had been active on the ground for criminal justice reform.”

In opening remarks at the summit, Luna highlighted the many challenges facing the formerly incarcerated throughout the reentry process:

• Compared with the general public, they have higher rates of health problems, both physical and mental, along with substance abuse issues.

• They struggle to find housing, along with reliable means of transportation.

• They have difficulty finding gainful employment, and that is sometimes a condition of probation. They often have poor job skills and limited work experience, and even if they are qualified, employers may be reluctant to hire.

In opening remarks at the summit, Academy for Justice Founder and Faculty Director Erik Luna highlighted the many challenges facing the formerly incarcerated throughout the reentry process.

“Recognizing these and other challenges facing former inmates, a broad coalition has grown in support of evaluating and reforming the reentry process,” Luna said. “The movement brings together policymakers, community activists, experts at think tanks and nonprofits, elected officials, religious groups, business leaders and others, all seeking to understand and improve reentry in the United States.”

More than 120 attendees took part in the summit, a diverse group representing all facets of that broad coalition.

Simulation exposes the challenges

The summit launched with a reentry simulation, in which participants played the role of just-released inmates. It laid bare the sometimes insurmountable challenges these men and women face.

Stations were set up throughout the simulation room, and each person had to try to reestablish themselves in society. They had to find work, but first they had to get proper ID. They had to find housing, pay rent, feed themselves and their children, go to the bank, show up for — and pass — drug tests, and check in with their probation officers. They needed to buy bus tokens to get from one place to the next, and with extremely limited budgets, they were forced to visit pawn shops and plasma donation centers, or take out predatory loans with outrageously high interest rates, all in a desperate attempt to make ends meet. At each stop, they were met with long lines, and they only had so much time to complete their tasks.

Many wound up homeless or back in prison. Others were barely able to get by.

The simulation was run by Tasha Aikens, a reentry specialist with the U.S. Department of Justice.

“These are the obstacles, challenges and barriers that many of these people face upon their return to the community,” she said.

Afterward, Aikens posed questions to the participants.

“How many of you thought it was frustrating and crazy?” she asked.

Throughout the room, heads nodded and hands shot up.

“How many of you thought the directions were unclear, that this was all too much? That you couldn’t find where you needed to go? How many of you thought the long lines were crazy?”

Again, there was unanimous agreement.

“Well, that’s reality,” Aikens said.

As the conversation continued afterward, one of the participants raised his hand to speak.

“I am somewhat of a plant, since I am a former member of Congress,” he said.

It was Gary Franks, a Republican who represented Connecticut in the U.S. House of Representatives from 1991 until 1997. He was one of the participants and admitted that he simply gave up halfway through, too frustrated to continue.

“But I am very impressed with this program,” Franks said. “And I strongly recommend that you invite the chiefs of staff of members of Congress to participate in a forum like this, because I served in Congress when the 1994 Crime Bill was passed, and I regret it. Also, I was chairman of the Welfare Reform Task Force for the Republican Party when I was in office, and I’ve seen some of the difficulties that you face. If you have a child, certain things should kick in automatically, and they do not. And if people knew — people who are in power to legislate and make decisions — if they knew about the challenges that everyone had to go through, it would be so worthwhile. For them to come here and participate in this, it could really allow for some differences to be made, not just in Arizona but across the country.”

Former inmate Benny Garcia was in the audience and agreed with Franks that it would be useful for policymakers to take part in the simulation. Garcia talked about being released from prison with a mere $7 to his name. He has since worked his way up to a management position at a Phoenix restaurant, and he said he had recently purchased his first house.

Andrew Fleming (left) works as an advocate for Banner Health, sharing his story to try to help others. Here he assists in the simulation exercise.

“But it’s been a struggle,” Garcia said. “And this simulation portrays everything that you’re having to go through. Getting your ID, getting treatment, finding ways to pay for everything.”

Andrew Fleming, who helped run the courthouse area of the simulation, concurred. A former inmate himself, he now works as an advocate for Banner Health, sharing his story to try to help others.

“The struggle is real when you get out,” he said. “That’s why I do what I do with these simulations. Because I think it’s crucial for the general public and people in the system and in the industry — mental health and criminal justice — to understand that it’s not as simple as just doing your time, getting out and making your own way. There are significant barriers that are still in place.”

Focusing on solutions

After the simulation, panel discussions were held on some of the more pressing issues facing former inmates:

• Barriers to housing and, specifically, “not in my backyard” objections.

• Employment and economic considerations, highlighting models for employer engagement.

• Treatment for mental health and substance abuse issues.

Attorney Kurt Altman works with the Right on Crime criminal justice reform group, serving as its state policy director for Arizona and New Mexico. He moderated the discussion on employment barriers, and he said the problems are fixable but that there needs to be more focus on raising awareness.

“The biggest message is that people need to realize there are barriers — and they are significant barriers,” he said. “Maybe some of the barriers have to be there, but we can remove most of them in different fashions and put these folks back to work. The two biggest issues that cause recidivism are lack of employment and lack of housing, and those are the two largest barriers to reentry once somebody has paid their debt to society. So we need to take a really close look at those issues and fix them, because they’re fixable.”

Valena Beety, the academy’s deputy director, said the summit was successful in not only helping people understand the difficulties facing those in the reentry process, but in generating and sharing creative solutions.

Valena Beety, the academy’s deputy director, speaks on a panel during the summit.

“These citizens are leaving prisons, and they are coming back to our communities,” she said. “Eighteen thousand inmates are released in Arizona each year, and the majority come to Maricopa County. It's happening. So what are the ways to make reentry successful so that prison isn’t a revolving door, so that we can reduce recidivism? And I really thought that there were a number of interesting ideas.”

For example, she said, there was discussion of incentivizing landlords to rent to the formerly incarcerated by creating a risk management fund, mitigating the risk of those tenants failing to pay rent. Another proposal focused on reentry navigators, who could work in prisons and help inmates prepare for and better handle the challenges of the reentry process.

Walton said the diverse backgrounds of the participants — activists, policymakers, religious and business leaders, former inmates — made for productive and informed discussions.

“That's really what the goal was, to bring out all of these different ideas, put these different perspectives on the table and have an open-minded and fair discussion about what we've been doing that has been working or what we haven't been doing that needs to happen,” she said. “I'm really happy with the amount of dialogue and interaction that we had.”

She said the academy intends to compile a list of recommendations that came out of the discussions, then disseminate those not only to the summit’s participants but to others involved in criminal justice reform, both locally and nationally.

Luna said there are a wide variety of motivations behind the criminal justice reform movement, but everybody is working together toward common goals.

“The people who support these efforts have different rationales,” he said. “They may be concerned about taxpayers footing the bill for the revolving door of incarceration. Or they may be progressive believers in human improvement. Others may be victims’ advocates, seeking to prevent further injury to the innocent. Still others may be supporters of social justice for the poor and communities of color. Some are people of faith, committed to the possibility of redemption. And many are Americans who view our nation as a land of second chances. But regardless of motivation, everyone has an interest in seeing former inmates successfully reenter society.”

Altman said simply getting all of these different people together in one place to share ideas was important and beneficial.

“The biggest thing that I found was how enlightened the participants became,” he said. “People didn’t realize — everybody knows there's a problem — but people didn't realize how important reentry is to making our communities better in the long run, helping the folks that need it, and how little we actually do in that area when people get released.”

And he hopes this is just the beginning for these types of forums.

“I appreciate the Academy for Justice and ASU Law participating in something like this,” he said. “I think the more symposiums or summits that we have that bring in a bigger and bigger cross section of the community, the better we’re going to be.”

More Law, journalism and politics

How ASU is leading the national conversation on journalism and AI

As artificial intelligence continues to advance at a rapid pace, journalism faces both unprecedented opportunity and profound…

5 takeaways about artificial intelligence and elections

Next year’s midterm elections are happening at a crucial time in the adoption of AI, with concerns that the new technology could…

ASU dominates Rocky Mountain Emmys, showcasing range of talent

Arizona State University stole the spotlight at the Rocky Mountain Southwest Emmys, walking away with an impressive haul of shiny…