Editor’s note: This story is being highlighted in ASU Now’s year in review. Read more top stories from 2020.

Twelve-year-old Jesse Senko is on vacation with his family in the Cayman Islands. They’re on a snorkeling tour. Senko is in the water, dazzled by the fish, when a big green sea turtle appears in front of him. Because he is a 12-year-old boy, he grabs it. The turtle takes off. Every 15 to 30 seconds it surfaces for air.

Senko’s mother is on the boat, throwing up, panicking, screaming “Come back!” The boat operator is cursing because what to do when a kid takes off on a turtle is definitely not in the employee manual.

Senko hears them screaming. He doesn’t care. He’s enjoying the ride. Sea turtles can hit close to 30 mph. Eventually the turtle returns to the boat. With one powerful flap of its flippers, it rids itself of its hitcher.

“Right at that moment I say to my parents, ‘That was awesome! I want to study these things!’” Senko says. “Ever since then I’ve been obsessed with sea turtles.”

Flash forward a few decades.

The East Pacific hawksbill turtle is among the most endangered sea turtle populations and one of the oldest creatures on Earth.

Senko is now a marine biologist and conservation scientist at Arizona State University. Most scientists spend their careers working on one problem, or part of a problem, or a tiny part of a problem. Senko is working on about 10 problems at once. Saving sea turtles is job one, but that’s related to sustainable fishing, which ties into resilient coastal communities. Engineering transformative fishing gear and reducing plastic trash in the oceans are other parts of his puzzle.

“Fishing gear is the greatest threat to sea turtles worldwide,” Senko says. “Sea turtles are vital for the health of the world’s oceans. They perform fundamental roles in ocean ecosystems, many of which are not fulfilled by other species. And humans need healthy oceans to survive and thrive.”

In the Sea of Cortez, on a tiny remote island lost in time and inhabited by one fishing family, all the strands of Senko’s work come together.

It’s about solving problems

He grew up on the coast of Connecticut on Long Island Sound. His father had him out on boats when he was in diapers. He has been fishing since he could hold a rod. He majored in fisheries and wildlife sciences at the University of Connecticut and received his master’s degree in wildlife ecology and conservation from the University of Florida.

He studies sea turtles, and Gainesville is about a 90-minute drive from the Atlantic. Why come to ASU in the middle of the desert, to earn a PhD in biology?

Sunrise at Isla El Pardito in La Paz, Baja California Sur, Mexico. The 2.5-acre island has been inhabited by a single family for more than 100 years.

“As scientists, we are great at assessing and identifying problems. We’re awful at solving them,” he explains. “ASU is about solving problems.”

Upon completing his PhD at the most innovative university in the country, he joined ASU’s new School for the Future of Innovation in Society, which works on solving all aspects of wicked problems and the unintended consequences behind new technologies and policies.

Senko’s passion is sea turtles, some of the oldest creatures on Earth. Whatever killed the dinosaurs, turtles survived it. They can live to 100.

The Mexican government banned sea turtle hunting in 1990. Get caught with one — dead or alive — and it’s a nine-year prison sentence. Recovery has been slow, though. Sea turtles swim right into the fishing nets and drown.

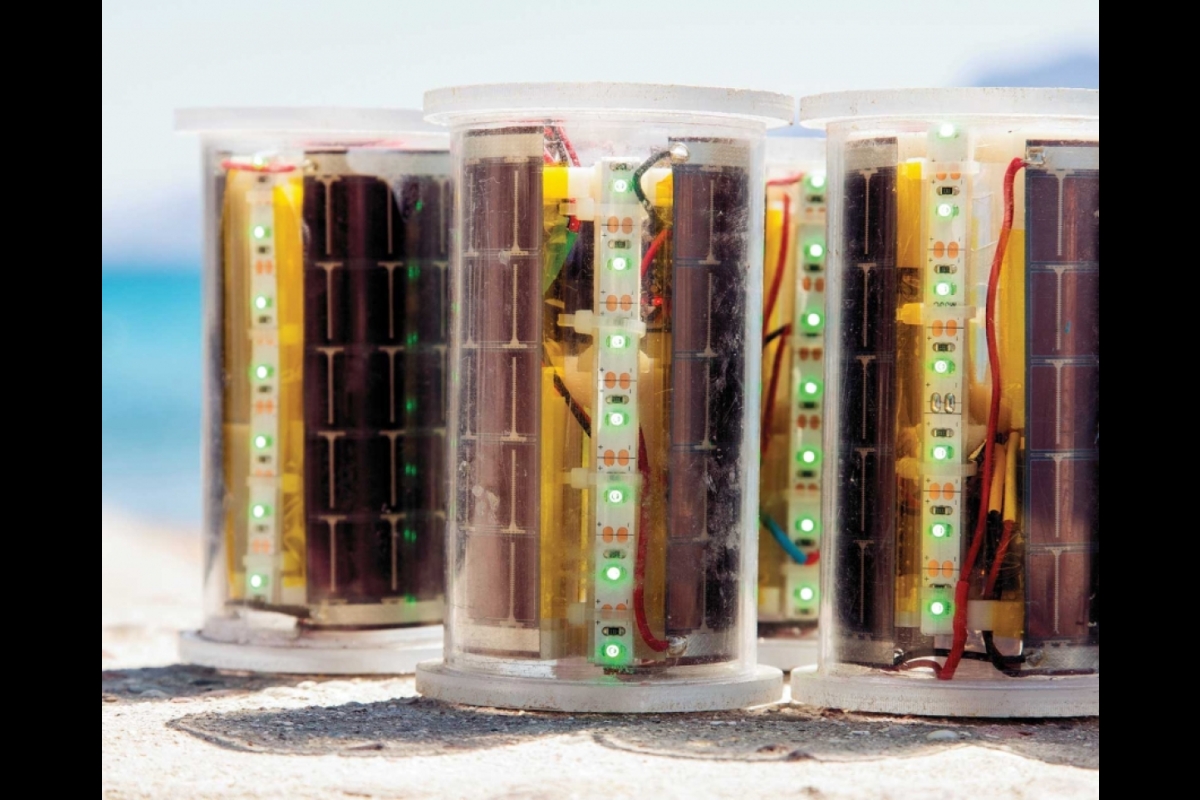

When Senko was working on his PhD in Baja California, he noticed lights put on gill nets to attract fish reduced sea turtle bycatch. Turtles and sharks can see nets and avoid them. As an experiment, he put battery-powered lights on fishing nets. He found a 50% reduction in turtle bycatch and a 95% reduction in shark and ray bycatch. He saw turtles swim up to nets and turn around.

But batteries and fishing lights are expensive. Glow sticks, used by commercial fishermen everywhere, are cheaper. But they’re usually tossed into the ocean after one night, adding to the global plastic problem.

With solar-powered fishing lights, fishermen can toss their nets on the deck or dock and the lights recharge themselves. This is where ASU’s interdisciplinary mission paid off — Senko isn’t an engineer.

So he cast around the university and assembled a team to develop solar-powered net lights. First, engineers: Jennifer Blain Christen, Mark Bailly, Christopher Lue Sang, Stuart Bowden and Michael Goryll from the School of Electrical, Computer and Energy Engineering in the Ira A. Fulton Schools of Engineering. The only environment harsher than the sea is space. They cracked the problem of creating something that functions on the ocean.

Second, another turtle expert: Agnese Mancini, the scientific coordinator of Grupo Tortuguero de las Californias, a Mexican nonprofit coalition of people and communities working to save sea turtles.

Finally, fishermen: brothers Felipe and Juan Pablo Cuevas, arguably the most famous among their peers in the waters of Baja California Sur. They hail from one of the most unusual places in the world, the remote island of El Pardito.

From here, Senko’s revolution is being launched.

Island of discovery

Civilization is far, far away from El Pardito — two long hours by boat from La Paz. The rest of the world could all fall apart tomorrow and the people of El Pardito would never hear a peep. When they did find out, their lives would not change very much at all.

The bay where the island is tucked is like Death Valley with water. Rocky scorched islands rise from the sea like giant extinct beasts, all haunches and spines and crouched tense flanks. Mangrove swamps apron some shores. Cactus forests crowd flats.

The island is tiny, about 2.5 acres, most of it hill. The island is part of the Islas del Golfo de California Protected Area, which is managed by Mexico’s National Commission on Protected Areas. Small houses built from a variety of materials are connected by trails and paths and stairs. Thatched palapas cover deep patios with hammocks and sleeping pads. Dried shark jaws, shells and a Turk’s head knot adorn rafters. Two dogs live on the island — a friendly black Lab and a Chihuahua that bites. There’s no electricity, no running water and no communications except for a radio. All the houses are solar-powered.

Look around and it dawns on you that this is what some people spend their whole lives dreaming about: million-dollar blue water views, fishing every day, waves lapping on the shore, fresh clams on the half shell for the taking.

The original people came to the island to escape mosquitoes. Juan Cuevas and his wife settled on El Pardito in 1927, raised a family and dove for pearls. Only two of the kids stayed. The rest left for the mainland.

The pearl fishery tanked in the late 1930s. During World War II the Cuevases fished for sharks; it was believed Vitamin A in shark livers improved military pilots’ night vision. Today, the family primarily fishes for yellowtail, grouper, halibut, snapper and triggerfish when using nets.

“As scientists, we are great at assessing and identifying problems. We’re awful at solving them. ASU is about solving problems. ”

— Jesse Senko

Conservation for the Cuevas brothers is not just turtles, it’s the whole marine ecosystem. They are working on eight projects with a variety of organizations.

They are as attuned to the sea as a farmer is to his land. They began to notice it wasn’t like it was when their father fished full time. They had to go farther and farther for good catches. The watershed moment came on a trip when they went all the way to the Pacific to catch sharks and didn’t bring in much.

They want to learn how to read the results of scientific studies so they can teach conservation to other communities in the area. They also want to learn how to fish better and preserve the balance of life. They’re well aware of what can go wrong. About 90% of the world’s fisheries are small-scale, and they’re not well-managed. If they’re not careful, they can put themselves out of business.

The brothers also want to see more studies on reproduction. Anecdotally they know more about different fish and their behaviors and connections than most marine biologists because they’ve seen it all for decades. Parrotfish are better off in the water because they play a more valuable role there than on a plate. There’s a nearby island where parrotfish were overfished, and now it’s overrun by sea urchins. The coral is suffering too.

They want to see more size restrictions and seasonal bans. The Mexican government is unwilling to implement either for two reasons: Both are unpopular, and they would be difficult to enforce.

Felipe Cuevas discussed the future he wants for his children and Senko’s impact. “I want them to learn how to fish, but I also want them to go to school,” he says. “I want them to learn about fishing and maybe research. I want my kids to be curious about history on the island.”

Lightbulb moment

Grupo Tortuguero has a permit to catch, study, measure, tag and release turtles. In the morning, the Cuevas brothers head out and catch a hawksbill turtle in a mangrove swamp about three miles from the island. Hawksbills have been a protected species since 1990 but are still poached for their tortoiseshell, which is used in combs, jewelry and eyeglass frames. In 15 years of research in Baja, this is only the second hawksbill that Senko has seen.

The turtle’s shell is covered in tiny organisms. “It’s like a town,” Mancini said.

At sunset, Senko goes out with the brothers to test the lights in a turtle-rich area. They drop two nets separated by a 200-meter length of line. One net has lights switched on — the treatment net. The other has lights turned off — the control net.

The lights look like a blinking landing strip in the darkness. The group takes off to go fishing for an hour. Leave the nets unattended for longer than an hour and a turtle could drown.

An hour later, after handlining snapper, grouper, two needlefish and a huge moray eel that the brothers did not want in the boat, they return to the nets. The middle light on the treatment net is not working. There’s a big dark area in the middle. And that’s exactly where they find a green turtle, away from the lights.

The lights work.

They haul the turtle on board, free it and release it back into the water. Sea turtles have gentle eyes and a bit of a frown, like a New York subway commuter enduring a bad smell.

Senko notes that the floating lights need to be weighted so they’re below the surface, casting more light down and less up.

More testing remains. Would different colors or wavelengths be more effective? What about adding a sound, like that of orcas? How about hanging them at varying depths?

And there are other fisheries to introduce the technology: Trinidad and Tobago, Peru, Indonesia, Philippines, Malaysia and Greece.

Senko’s turtle ride has only just begun.

Top photo: ASU researcher Jesse Senko (right) deploys a solar-powered illuminated net in the Sea of Cortez, which renowned explorer Jacques Cousteau described as the “aquarium of the world.”

Photos by Lindsay Lauckner Gundlock. This story appears in the winter 2020 issue of ASU Thrive magazine.

More Science and technology

Lucy's lasting legacy: Donald Johanson reflects on the discovery of a lifetime

Fifty years ago, in the dusty hills of Hadar, Ethiopia, a young paleoanthropologist, Donald Johanson, discovered what would become one of the most famous fossil skeletons of our lifetime — the 3.2…

ASU and Deca Technologies selected to lead $100M SHIELD USA project to strengthen U.S. semiconductor packaging capabilities

The National Institute of Standards and Technology — part of the U.S. Department of Commerce — announced today that it plans to award as much as $100 million to Arizona State University and Deca…

From food crops to cancer clinics: Lessons in extermination resistance

Just as crop-devouring insects evolve to resist pesticides, cancer cells can increase their lethality by developing resistance to treatment. In fact, most deaths from cancer are caused by the…