Editor’s Note: This Q&A is part of a series of articles focusing on military veterans who are part of ASU’s faculty. Over 460 veterans work at ASU, including 151 in the faculty and 312 who are university staff.

He is a Marine Corps veteran, licensed attorney, literary scholar and a sought-after professor at the Arizona State University college known for recruiting the nation’s most academically outstanding undergraduates.

Michael Stanford, a faculty fellow at Barrett, The Honors College, has a long history working at the school and believes the honors program is a great opportunity for some military veterans.

It is understandable why a veteran might shy away from something like Barrett, Stanford said. Veterans are typically transfer students, some have family responsibilities, and many are trying to complete their studies in fewer than four years.

“I think we only have about 18 veterans out of 6,000 students,” Stanford said. “We are trying to get the word out that for certain types of veterans, it’s definitely worth picking up the challenge of Barrett.”

As someone who served in the Marines for three years and quickly climbed to the rank of sergeant before his term was up, Stanford is no stranger to challenges. He started at Barrett in 1992 as a lecturer, taught Barrett’s signature Human Event seminar for 15 years, and rose to direct the school’s summer study program in the British Isles from 1995–2001. He then started law school in 2002, earned a law degree in 2007 and went on to serve as a trial attorney with the Maricopa County public defender’s office for over five years. Stanford returned to Barrett in 2013 as full-time faculty.

He spoke to ASU Now about his path toward academia, his short yet exciting time in the military — including pugil stick fights and flying in the Caribbean with the Prince of Wales — and his Barrett pitch to ASU's student veterans.

Question: How would you describe your time in the Marine Corps? What was the experience like for you?

Answer: In a sense I was born into the Marine Corps, because I was born on Camp Lejeune, the Corps’ big base in North Carolina, where, coincidentally, I was later stationed. My father was a career Marine officer who served for 30 years and fought in the Pacific, Korea and Vietnam, then retired as a colonel. He won the Navy Cross on Okinawa. Very imposing guy. My time in the Marines was one-tenth as long and one-fiftieth as eventful as his.

I started college at Duke in 1971, right out of high school, but by the end of freshman year I was bored with school and dropped out. I wound up joining the Marines as a private because I wanted a change and a challenge. This was very much not at my father’s instigation. In fact he was quite surprised at my choice, having thought of me as more or less a hippie pacifist. I went to boot camp at Parris Island, a very intense experience.

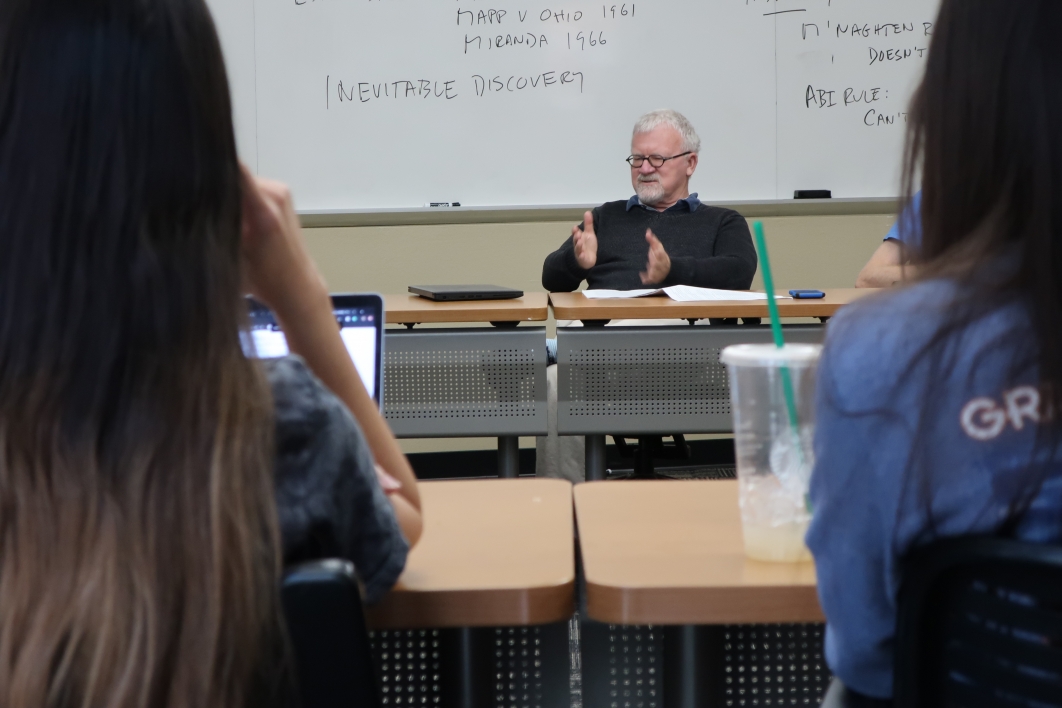

Faculty Fellow and Professor Michael Stanford leads a class discussion about crime and punishment Nov. 6, 2019, at Barrett, The Honors College. Photo by Jerry Gonzalez/ASU Now

After boot camp, I went for advanced infantry training in Camp Pendleton, California. This was less psychologically stressful than boot camp but more physically demanding. A lot of the time was spent in uphill forced marches with full packs. But I liked looking down at the Pacific from the hills and sleeping under the stars. As an Easterner I was intrigued by the tumbleweed blowing across the trails and the sobbing of coyotes at night.

Though my military occupational specialty was rifleman (0311), I wound up being stationed first in the Marine guard detachment on the Naval Air Station in Atsugi, Japan. The duty there was less than inspiring, consisting as it did of checking cars at the main gate, patrolling the base and running a small lock-up. We carried .45s and wore MP armbands but the real police work on the base was done by the Shore Patrol, who were actually trained for the job. But I had partly grown up in Japan — my father had been stationed in the embassy there — and was fascinated by the country’s culture, so it was nice to be back. I traveled a bit around the country — saw the temples of Kyoto and the Great Buddha of Kamakura —and took karate classes at a traditional dojo where I was the only gaijin and the other students always wanted to spar with me, probably to see if they could beat the — relatively — big American. Which they usually could.

After Japan I went to an infantry battalion in Lejeune, where, among other things, I had the fun of participating in something called the “Super Squad” competition, ostensibly to choose the best infantry squad in the Marine Corps. My squad won at the battalion and regiment levels but failed to take division. I’ve often wondered what the prize would have been if we’d gone all the way. Promotions all around? A keg of beer? Probably just our pictures in the Marine Corps Gazette.

Speaking of promotions, I did manage to make sergeant (E-5) before my enlistment was up. This seemed to make my father proud. But after three years and three months, while I was grateful in lots of ways for the experience, I was ready to be a civilian — and student — again. So I returned to Duke, with the very welcome assistance of the GI Bill.

Q: Any memorable moments from your time in the service?

A: It’s hard to isolate one or two memorable moments out of three years. But I won’t forget collapsing with heatstroke at the finish line of the final physical fitness test on Parris Island. I came to in a Jacuzzi full of ice, with two corpsmen scraping my skin with ice cubes to bring the blood to the surface. This earned me a pleasant 10-day stay in the hospital and away from boot camp. But the doctor in the intensive care unit told me that the guy in the bed next to mine had probable brain damage from his own case of heatstroke. Ever since I’ve had an intense wariness of hot weather. I often wonder what I’m doing in Arizona.

And here’s a lighter, quirkier moment: My battalion was on maneuvers in the Caribbean with the British Navy and Marines We were in formation 100 meters from a helicopter, waiting for it to take us to the other side of the island of Vieques. My platoon sergeant said, “Our pilot is the Prince of Wales.” When I expressed my skepticism, he handed me his binoculars. The pilot walking out to the helo did indeed have the unmistakable beaky profile of Prince Charles, then a serving officer in the British Navy. He and his copilot ferried us efficiently to our destination, and we left the helicopter by rope as it hovered, so I never did get to actually talk to the prince, but at least I can say that a future king of England was briefly my chauffeur.

Q: How did your time in the service help influence your academic career?

A: I can confidently say that the many interesting skills I picked up in the Marines — fighting with pugil sticks, field stripping an M16, throwing a hand grenade 40 meters — have had absolutely no application in my subsequent career as a literary scholar and university teacher. But it was a given that I’d return to college, and my time in the Corps solidified my choice to be an English major. There’s an awful lot of downtime in the peacetime infantry, and I filled mine reading voraciously in fiction, poetry and history. Thankfully, both Atsugi NAS and Camp Lejeune had well-stocked libraries.

My reading habit was unusual among my fellow grunts but not unique. My platoon sergeant in Lejeune, Mike Giles, was a hard-charging African American NCO who would go on to become a drill instructor. He was also a self-taught intellectual, superbly articulate and well-read. I once saw him sprawled on his rack reading the Selected Letters of Virginia Woolf. I amused myself trying to count the number of stereotypes he was busting by doing so. I suspect that every service includes a fair number of such autodidacts in its enlisted ranks.

Q: What advice would you give to vets at ASU?

A: I’m hard-pressed to think of any relevant advice I could give this generation of vets based on my own — almost half a century old! — service. Besides, I’m not sure our vets need any advice. All the vets I’ve taught in my classes at Barrett, The Honors College have been impressive people— mature, disciplined, focused and idealistic. So rather than give advice, I’d like to make a request. If you’re a veteran who’s an undergraduate at ASU, and has at least two years remaining till graduation, I would ask you to consider applying to Barrett. A Barrett education comes with extra challenges but also extra opportunities — and aren’t challenges and opportunities exactly what you enlisted for?

Lots of information about Barrett is available on the ASU website. For details on applying, please contact our director of admissions, Keith Southergill, at keith.southergill@asu.edu. He’ll be happy to hear from you, and I hope to see some of you in my class.

Top photo: Faculty Fellow and Professor Michael Stanford poses for a photo with U.S. Army veteran and student Chad Elsner on Nov. 6. 2019, prior to the start of class at Barrett, The Honors College. Photo by Jerry Gonzalez/ASU

More Sun Devil community

Barrett program unlocks study abroad for first-year honors students

Twenty first-year students from Barrett, The Honors College at Arizona State University are spending their second semester studying abroad in Rome, Italy.Traveling in a tight-knit honors community…

A champion's gift: Donation from former Sun Devil helps renovate softball stadium

Jackie Vasquez-Lapan can hear the words today as clearly as she did 17 years ago.In 2008, Vasquez-Lapan was an outfielder on Arizona State University’s national championship-winning softball team,…

Student-led business organization celebrates community, Indigenous heritage

ASU has seen significant growth in Native American student enrollment in recent years. And yet, Native American students make up less than 2% of the student population.A member of the Navajo Nation,…