Annual Hacks for Humanity showcases how diversity fosters creation

A Hacks for Humanity participant wears a T-shirt showcasing the various types of creators around whom the event is organized.

A nuclear physicist, a high school student and three undergraduates find themselves sharing a table at Arizona State University. Fueled by energy drinks, late-night snacks and a break for silent disco, their mission over the next 36 hours is to identify an issue impacting society and hack their way to a solution.

It could be the opening scene of an indie science fiction movie. But the group was actually one team taking part in the sixth annual Hacks for Humanity.

The event, which took place Oct. 19-20 on ASU’s Tempe campus, is an initiative of The College of Liberal Arts and Sciences’ Project HumanitiesThe award-winning initiative brings together individuals and communities from around Arizona to instill knowledge in humanities study, research and humanist thought. Project Humanities facilitates conversations across diverse communities to build understanding through talking, listening and connecting.. It gathers businesspeople, humanists, artists, software developers and engineers for an entrepreneurial weekend of brainstorming, building and pitching technical tools for the benefit of society.

Each year, participants are asked to create projects around particular themes rooted in the seven core values outlined by the project’s founding initiative, Humanity 101: kindness, compassion, integrity, respect, empathy, forgiveness and self-reflection.

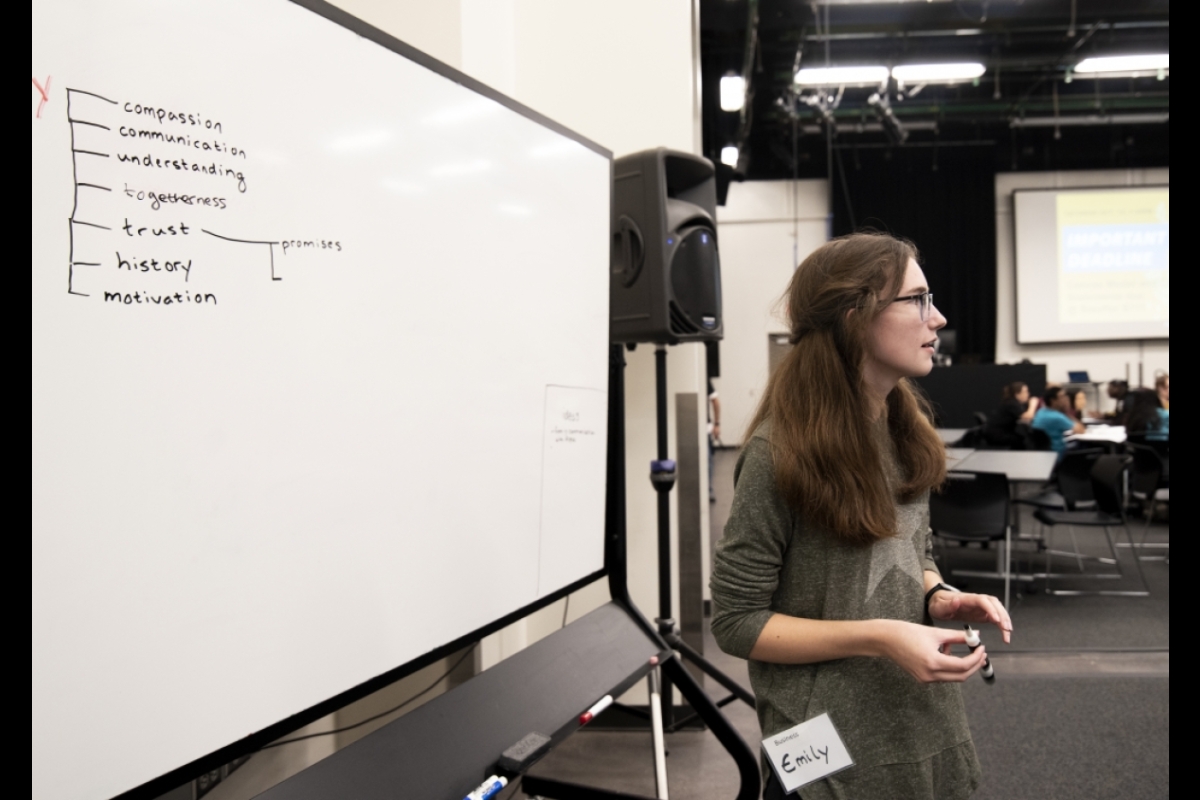

After a weekend of strategy, coding and troubleshooting, six teams presented their creations focused on finance, food and family to a panel of judges from business, technology and entrepreneurial backgrounds. An app called Promise, in which children complete chores in exchange for rewards and parents monitor their tasks, won first prize.

Runner-ups included Alleyway, an online platform connecting family members separated by adoption, war, natural disaster or refugee relocation, and A New Hope, a service that aims to provide funding for people wanting to visit a dying family member in another state.

Other projects included a platform connecting food banks with restaurants and grocery stores with a surplus of food and a wearable device that monitors blood pressure and stress levels to provide instantaneous mindfulness tools.

Ram Polur, a local software engineer and epidemiologist, was part of the winning team of the inaugural Hacks for Humanity six years ago. Back then, his team created a product that used keyword scanning technology to monitor Twitter for users writing tweets that indicated suicidal thoughts. He’s since returned to Hacks for Humanity events to serve as a mentor and volunteer.

“People have increasingly started hearing about the projects coming out of this event and I think that has in turn ramped up project creativity and diversity,” he said. “Developing applications really does require a multipronged approach; you need business sense, you need empathy, you need art and humanity, you need all of these different folks to solve the problems we face today.”

Diversity as a tool for creation

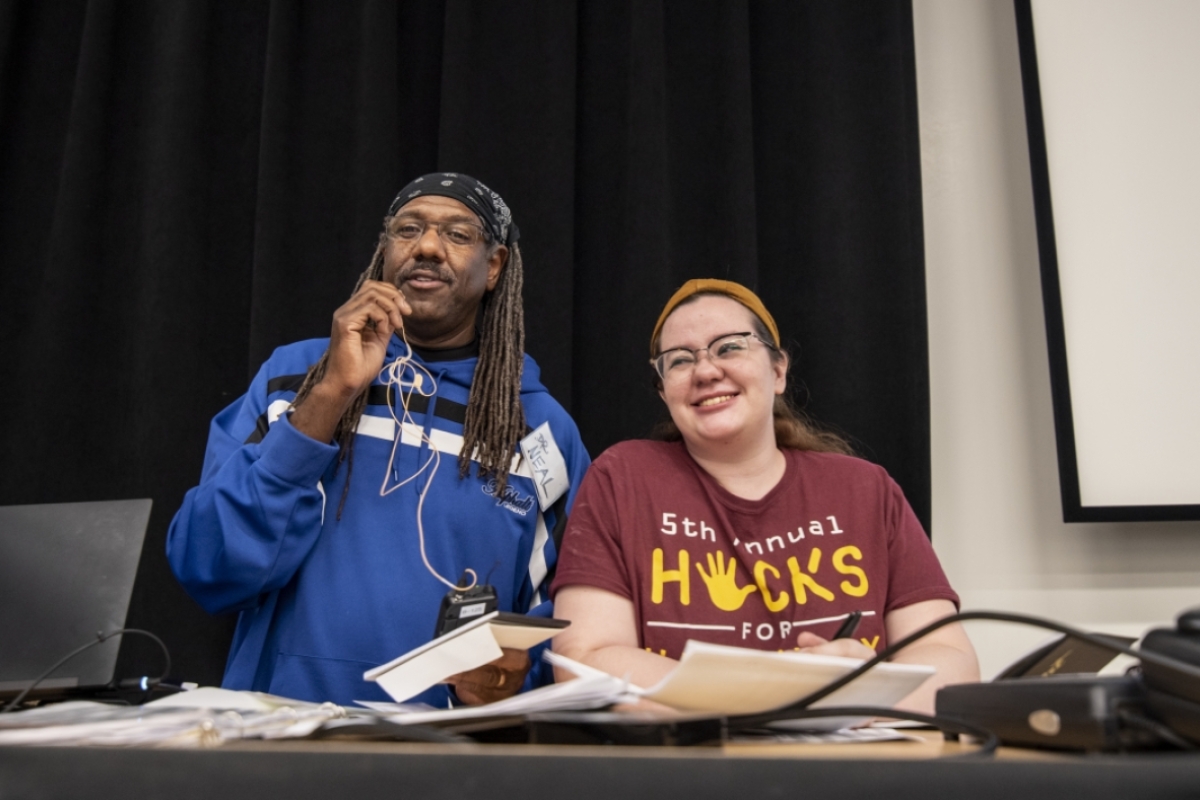

Participants arrived early Saturday morning to form teams of four to five people with varying areas of expertise and backgrounds. Unlike in previous years, this year’s teams were chosen using an algorithm, a change Project Humanities Director Neal A. Lester said aimed to increase diversity and instigate new conversations among people that might not normally cross paths.

class="glide image-carousel aligned-carousel slider-start glide--ltr glide--slider glide--swipeable"

id="glide-478179" data-remove-side-background="false"

data-image-auto-size="true" data-has-shadow="true" data-current-index="0">

data-testid="arrows-container">

“This is about on-the-spot creation that happens organically, and it’s about seeing what communities can emerge from talking to people who don't look like you, think like you or even necessarily work like you,” Lester said. “We are deliberately trying to get the coders and the non-coders to the table, because the reality is just because you can code doesn't mean you can pitch or do the research or design the project — at the core, it’s about challenging the notion that technology has to be separate from our humanity.”

Project Humanities communication and outreach coordinator Rachel Sondgeroth is in her final year of concurrent bachelor’s degrees in global studies and religious studies in The College. She’s worked with the project for the last four years and sees the hackathon as a live example of how humanities figure into the real world.

“This year has the most interdisciplinary teams we’ve ever seen, and I think that really shines through in the products people are coming up with,” she said.

Arcelious Stephens is a retired water policy expert with the Arizona Department of Environmental Quality and a three-time participant of the hackathon. His team created A New Hope, which took third place at the event. He said this year’s intimate setting and randomized teams gave way to projects that felt focused and highly unique.

“The size of the event created a much more intense environment and an exciting space to create,” he said. “We had a freshman and a junior, two professionals and myself, a retiree. We had two white guys, two women and me, a black guy — the mixing of all that really made for some interesting avenues I don’t think we would have come to on our own.”

A new way to hack

Hackathons have been taking place around the world for at least the last decade, with teams of computer science aficionados competing to build a product that wows the judges and, with luck, ends up in the hands of investors to bring it to the next step. Lester said Hacks for Humanity stands out because it attracts participants spanning ages and areas of expertise for a weekend focused not just on technological innovation itself, but on how it interacts with our daily lives.

“Project Humanities is asking questions like: ‘How did we get here in society? Why do we do the things that we do, and are there multiple ways of looking at things?'” Lester said. “That's precisely what this hackathon embodies, because it's not just 36 hours of coding, it’s about figuring out how these products enhance the human experience.”

Fostering a different kind of hackathon is one reason participants also attend workshops, this year on bias in technology and navigating the process of ideation, pitching and implementation. The weekend was also supported by a growing list of volunteers, mentors and sponsors from enterprises including Amazon, Honeywell, State Farm, ADP and ASU Entrepreneurship + Innovation.

For Jullian Flemister-King, a software developer at Amazon, being a mentor was a chance to lend a hand to transdisciplinary hacking in action.

“I mentor and participate in a lot of hackathons, and not a lot of them have this overall theme of trying to give back to the community,” he said. “I think this one is great because it’s transdisciplinary, so you have a lot of different crowds coming in wanting to contribute.”

Judges also came from diverse professional backgrounds.

Denise Meridith is a local entrepreneur and business consultant whose most recent venture is the corporate networking firm World’s Best Connectors. Judging the competition was an extension of a career spent innovating.

“I’m very excited by rebels in today’s businesses and that’s also what excites me about this event — these projects are trying something different, willing to take risks and wanting to help humanity,” she said. “We are in difficult times right now, and I think it’s important to work on your small part of the universe. I think that’s what’s happening here — people are coming up with solutions that affect them and others.”

The technology of being human

Humanities and technology are fields many might consider to be on opposite sides of the academic spectrum. But bridging the two is becoming vitally important as technology embeds further into everyday life.

Phillip Pipkins, an alumnus of The College who graduated in 2012 with a bachelor’s degree in English and a minor in film and media studies, served as a Hacks for Humanity mentor and presenter this weekend. He saw the role as a chance to showcase how liberal arts and technology intersect.

“There’s this perception that if you’re pursuing a liberal arts degree, you won’t be able to do something in science, technology, engineering and math fields,” said Pipkins, who now works as the design lead for strategic initiatives at Silicon Valley Bank. “But it’s actually a discipline that gives you a leg up when it comes to thinking creatively and being able to break down concepts in a simple, accessible way — sometimes I find I’ll bring up an idea that feels very outside the box to people coming from a traditional STEM background, and that’s a positive thing.”

Hacks for Humanity 2019 was smaller than events in previous years. But participants said they appreciated the one-on-one attention they received from mentors and the space they had to create.

First-time hackathon participant Heather Jackson is an energy innovation consultant for electric company Arizona Public Service whose professional background spans nuclear physics, business management and marketing. While the wearable device product she helped create didn’t win, she says her group intends to take the idea beyond the competition.

“We’re already planning another meeting at my house to discuss the next step,” she said. “I feel like I’m walking away from this weekend with a team and a product — we got great feedback from the judges and now we want to see if this thing has legs.”

Kirsten Kraklio contributed to this report.

More Science and technology

Science meets play: ASU researcher makes developmental science hands-on for families

On a Friday morning at the Edna Vihel Arts Center in Tempe, toddlers dip paint brushes into bright colors, decorating paper…

ASU water polo player defends the goal — and our data

Marie Rudasics is the last line of defense.Six players advance across the pool with a single objective in mind: making sure that…

Diagnosing data corruption

You are in your doctor’s office for your annual physical and you notice the change. This year, your doctor no longer has your…