Love at first bite: Dynamic duo find research home in Arizona’s mosquito hot bed

Arizona State University School of Life Sciences researchers Krijn Paaijmans and Silvie Huijben have studied disease and insecticide resistance in several countries. They now find themselves in a mosquito hot bed here in Arizona. Photo by Samantha Lloyd/ASU VisLab

They go together like milk and cookies. Peanut butter and jelly. Batman and Robin. Disease and mosquitos. Wait, what?

Like other famous pairs, Krijn Paaijmans and Silvie Huijben are a dynamic duo. They just happen to study mosquitos.

Paaijmans and Huijben, both assistant professors with Arizona State University’s School of Life Sciences, met while in college in the Netherlands.

At that time, Paaijmans got hooked on studying mosquitos after they piqued his interest while working on a research project in Kenya. At the same time, Huijben was looking for a master’s degree project in parasitology.

Paaijmans knew of one involving penguins at the zoo.

“I wasn’t really interested in malaria, but there was this problem of penguins in the zoo getting malaria and I thought, ‘Well, that’s interesting,’” Huijben said. “It’s a very common disease among passerine birds where they don’t really get sick, but penguins aren’t exposed to it so they’re susceptible and easily die.”

Path to Arizona

Huijben spent her master’s degree learning about the species of malaria infecting these penguins and the species of mosquito that carried it. She had one foot in Paaijmans’ research world and never really left it.

Malaria and mosquitos — the perfect fit.

“Now, I’m just trying to avoid that she’s taking all my work,” Paaijmans joked. “I had to come up with another specialization.”

He moved with her to Pennsylvania and the two married while she was working toward her PhD.

Then, she moved with him to Barcelona, Spain, for an assistant research professor position. Her interest in malaria and mosquitos grew stronger after she joined Paaijmans for months at a time at a field station in Mozambique studying malaria elimination. Developing a research project in that area meant bringing the whole family, including their children, ages 1 and 3 at the time, so they could stay together during the field season.

Finally, last year, he moved with Huijben to Arizona, where they are both studying mosquitos and she will continue to study disease.

Decreasing insecticide resistance

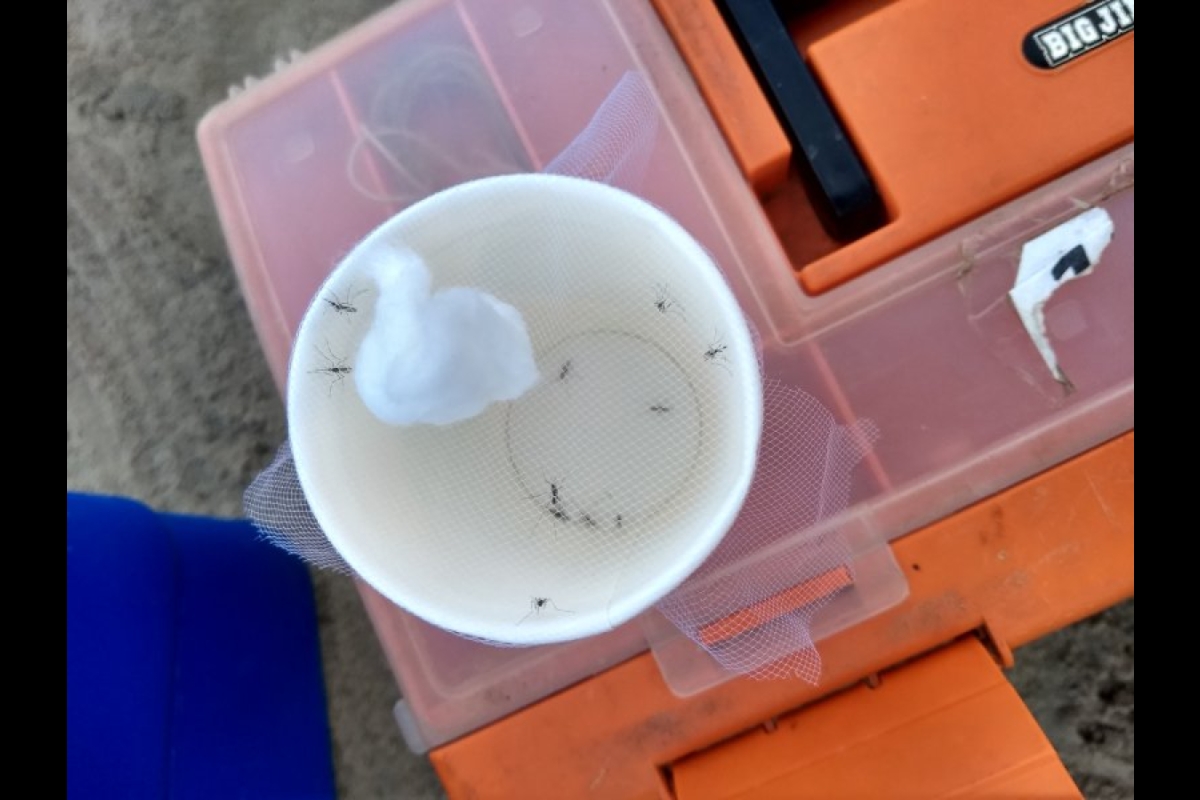

Their Arizona research efforts recently got a huge boost: Their temporary insectary was completed, allowing them to work with live specimens again. And, Huijben was approved to start studying malaria specimens in the lab.

When then were working in Mozambique, they both remember watching mosquitos sit on insecticide-treated bed nets for hours when they should have been killed in minutes. These mosquitos often carry malaria, which is a life-threatening disease that affects millions of people worldwide.

Now, they each have their own research program aimed at reducing this problem.

Huijben is studying insecticide resistance in mosquitos, particularly those that carry malaria, and is looking for ways to prevent it. There are several computer models that predict methods to reduce resistance, but without testing them in lab and field environments, they are only predictions.

There are two main ways to reduce resistance. Both involve using multiple insecticides in villages, much like you would use a drug cocktail to treat a complex infection. One way is to rotate usage of insecticides so that mosquitos cannot develop a resistance to just one. Another is to treat half of the village with one and the other half with another so that if a mosquito develops resistance to one, it will still die when exposed to the other.

Now that she has a temporary insectory, she can test these methods to see which leads to a lower percentage of resistance in the population.

Paaijmans focuses more on implementing new trapping and deterrence tools in the field. Currently, bed nets are the standard, but those don’t help if the mosquitos are biting outside during the day or are in the house before you go to bed. Thus, he works on different types of traps, such as bait traps or funnel traps at the top of the bed nets that attract mosquitos and catch them at night.

“The standard approach to malaria control is giving bed nets and spraying houses, but we see lots of areas where mosquitos are biting before you go to bed. Or outside. Or during the day time,” Paaijmans said. “So, millions of dollars of funding are going into these tools but they might not be as effective as everyone thinks.”

His field experiments include having people sit outside with legs exposed and capturing mosquitos that try to bite them so he can learn about them: What species are they? What diseases can they carry? When are they biting? Where are they located?

He also wants to understand how current tools are being used since people often ignore or misuse the tools designed to reduce the spread of malaria.

He is currently working on an electronic mosquito barrier that would create electric fields between wires. People who protest the use of mesh in their windows because it reduces airflow in the summers could use this technology to keep mosquitos out. Military units could use it to keep mosquitos out of their temporary facilities.

Here in Arizona, it could be used around storm drains where mosquitos congregate to lay eggs. Then, either they would be blocked from laying eggs or be trapped after laying eggs.

Arizona is a mosquito 'hot bed'

Though excited about the insectory, this is only a temporary facility. In a year, they will have a high-security, negative air pressure insectory with flight rooms and large experiment areas where they will be able to bring mosquitos back from Mozambique and conduct their experiments on the mosquitos that carry diseases they are studying.

Currently, they can only have disease-free, local mosquitos in their temporary facility.

But luckily, the researchers are living in a mosquito hot bed.

“Vector control says Arizona is the highest density of mosquitos of anywhere in the United States and that’s why people love to come here and work with them,” Paaijmans said. “All of the storm drain water creates perfect conditions.”

Huijben added, “When we do our research in Guyana or Mozambique, we’re very happy if we get 100 in a trap, 50 even. But usually, it’s like three or eight. But here they had one trap, one night, 80,000 mosquitos. In just one trap.”

In the next year, they can pilot test many of their experiments on local populations, strengthening their hypotheses before bringing back mosquitos from Mozambique.

“Patterns will be quite similar. They’re just different vector,” Paaijmans said. “You never know until you do the experiment. We just don’t know how that will it will apply to malaria mosquitos. Many biological life history traits that we study in one mosquito applies to other mosquito species as well, but we have to test on both.”

More Science and technology

2 ASU faculty elected as fellows to National Academy of Inventors

Arizona State University faculty members Bertram Jacobs and Klaus Lackner have been elected as fellows to the National…

Harvesting satellite insights for Maui County farmers

Food sovereignty can refer to having access to culturally significant foods, but Noa Kekuewa Lincoln believes it goes farther…

Google grant creates AI research paths for underserved students

Top tech companies like Google say they are eager to encourage women and members of historically underrepresented groups to…