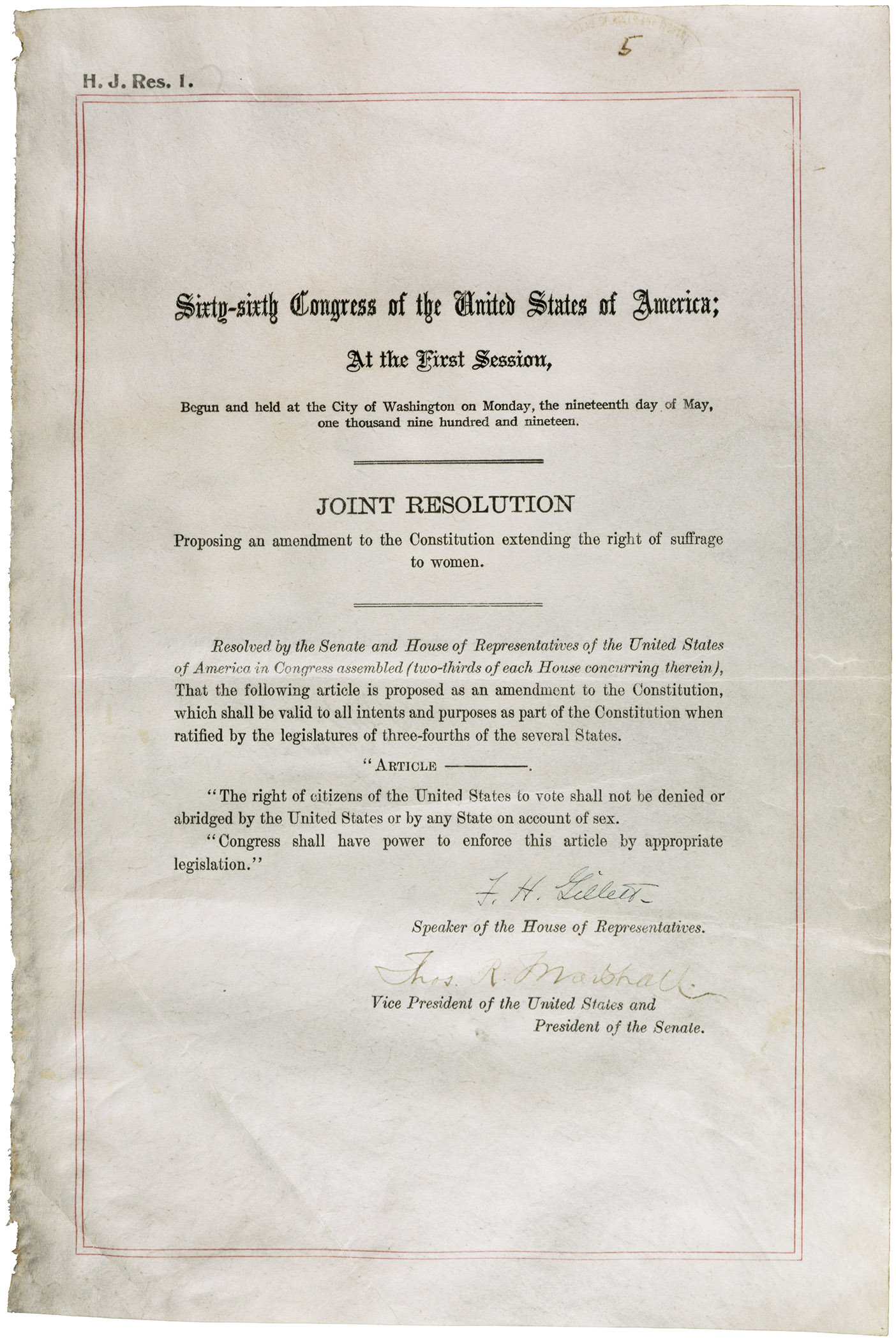

19th Amendment Resolution. Courtesy of National Archives General Records

After 304 votes in the House of Representatives, 56 votes in the Senate, 36 state endorsements and one more declaration to put it into effect, the 19th Amendment — the proclamation that gave American female citizens the right to vote in all elections — took its place in the U.S. Constitution on Aug. 26, 1920 — 99 years ago.

You’ve come a long way, ladies — and longer still if you consider what came before and after the passage of the amendment.

In a yearlong series in commemoration of the 100th anniversary of the ratification of Amendment XIX in 2020, ASU Now is exploring the history of the women’s suffrage movement, its influences and its influencers, through the study and practice of scholars at Arizona State University. Follow along on Twitter — @asunews — all year as we share quotes, characters and historical tidbits from the long road to the vote.

Below, peppered with historical quotes from activists, ASU researchers discuss the challenges faced both externally and internally within the women's movement, as competing priorities led to fractures and additional obstacles. History is rarely simple.

—

"All the nations of the earth are crying out for liberty and equality, Away, away with tyranny and oppression!" — Maria Stewart (teacher, journalist, abolitionist, women’s rights activist)

“The history of the United States has been a struggle for the right to vote,” said Stanlie James, professor of African and African American studies in ASU’s School of Social Transformation. From pre-Civil War abolitionists to present-day reformists, James says people have been arguing about who has the right to vote since the promulgation of the U.S. Constitution. And although unified in the purpose of including women’s voices in the votes that have decided leadership and helped to shape the country, the suffrage movement itself was not without debate — either before the passage of the amendment, or after.

“The suffrage movement is intertwined in other forms of collective action such as the movement to abolish slavery, the labor struggles of working girls in the textile mills, and creation of benevolent societies to assist the poor,” said Mary Margaret Fonow, professor of women and gender studies in the School of Social Transformation. But although the strategies, tactics and organizational forms of these various movements and campaigns may have influenced each other for the betterment of their causes, Fonow says societal divisions in race and class among these groups presented extreme challenges in the long history of the women’s movement.

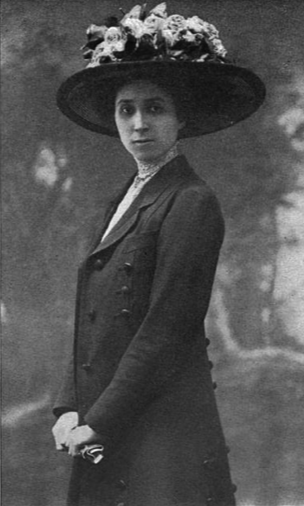

“It is a cause of astonishment to us that you white women are only now, in this 20th century, claiming what has been the Indian woman’s privilege as far back as history traces” — Laura Cornelius Kellogg (Oneida leader, author, activist)

Laura Cornelius Kellogg. Courtesy of Quarterly Journal of the Society of American Indians/Wikimedia Commons

“What makes the 19th Amendment so interesting to me is that Native Americans as a people didn’t win the right to vote until 1924 — four years after the amendment was adopted into the Constitution,” said Angela Gonzales, whose research includes indigenous studies and women and gender studies in the School of Social Transformation. At the height of the women’s suffrage movement, Native American women were more inclined to focus on group rights, according to Gonzales. But that did not hinder intellectuals such as Laura Cornelius Kellogg and Marie Louise Baldwin from publicly supporting the women’s movement as well.

“A number of Native American women came from societies where women were not marginalized as were women in the mainstream,” says K. Tsianina Lomawaima, a professor of justice and social inquiry in the School of Social Transformation and the Center for Indian Education. So, to many like Cornelius Kellogg, a member of the matrilineal Oneida Nation, the mainstream women’s movement was looked upon with some amazement. Women’s rights and responsibilities, according to Lomawaima, were not new ideas for many Native American women.

“The way to right wrongs is to turn the light of truth upon them.” ― Ida B. Wells-Barnett (journalist, educator, civil rights activist, suffragist)

African American women also presented perspective in the campaign for women’s rights that, although rooted in antislavery efforts, began to divide black and white women at the introduction of the 15th Amendment in 1870. After an energizing show of unity at the first women’s rights convention 22 years earlier in Seneca Falls, New York, the suffrage movement splintered over the amendment that would enfranchise black men the right to vote — but not women of any race. The American Woman Suffrage Association (AWSA), formed by abolitionist and reformer Lucy Stone and her husband Henry Brown Blackwell, supported the 15th Amendment. The National Woman Suffrage Association (NWSA), founded by Susan B. Anthony and Elizabeth Cady Stanton, opposed it — unless it included women. It did not. And so began the rift that would move women to take sides in a debate that would, much later, challenge ideas of inclusion, intersectionality and political expediency in academic studies.

Ida B. Wells-Barnett. Courtesy of Wikimedia Commons

According to Fonow, abolitionist and women’s rights activist Sojourner Truth became an early example of the role black women would play as “bridge leaders between the women’s movement and the civil rights movement” through her work with the rival women’s suffrage groups, which were still largely composed of white women. But the anti-lynching campaigns inspired by the work of journalist and suffragist Ida B. Wells-Barnett would soon become a signature form of black women’s collective action and highlight the differences in agenda and priorities between black and white women in the women’s suffrage movement.

There were other pressing priorities for black women as well.

James says black women’s reasons for wanting the vote were oriented around a feeling of responsibility to take care of the black community and the necessity of protecting their “honor” against rampant occurrences of discrimination and sexual abuse by white men. For black women, James says having the vote would mean they could participate in the process of selecting the officers running their towns and act on opportunities to serve on juries.

“We ask only for justice and equal rights — the right to vote, the right to our own earnings, equality before the law.” — Lucy Stone (abolitionist, orator, suffragist)

Flashes of progress came in the midst of the long struggle when a handful of frontier states gave way to women’s suffrage. Wyoming led the way in 1869, enfranchising women in the territory. And in 1870 Louisa Ann Swain of Laramie, Wyoming, earned the distinction of becoming the first woman in the United States to cast a vote in a general election. Utah followed Wyoming in granting women suffrage. Colorado and Idaho were also among the states that granted women suffrage in the late 19th century.

Lucy Stone. Courtesy of Library of Congress

On the global level, New Zealand became the first country in the world to grant women the right to vote in 1893. Ten more countries would grant women suffrage before the 19th Amendment was ratified in the United States in 1920. Many more would follow, with Saudi Arabia becoming the latest country to grant women suffrage in 2011.

Challenges persisted, however, even with the 19th Amendment fully anchored in the U.S. Constitution. It took almost 40 years after the passage of the Snyder Act in 1924 for all 50 states in the United States to recognize Native Americans as full citizensNew Mexico was the last state to enfranchise Native Americans in 1962 and therefore eligible to vote. It would take another three years, with the passage of the Voting Rights Act of 1965, for Native Americans, African Americans and other disenfranchised groups to fully exercise their legal right to vote under the protection of the federal law that sought to end discrimination and violence against people of color at the polls.

But even today, activists and civil rights groups continue to fight voting laws perceived as discriminatory.

"I know nothing of man's rights, or woman's rights; human rights are all that I recognize." — Sarah Moore Grimke (abolitionist, writer, suffragist)

“Suffrage was neither the beginning nor the end of women’s collective action,” said Fonow. She says women’s activism has since taken on different forms, pointing to numerous examples of women participating in political parties, working to end segregation and fighting for equal access to education and for equal pay. “It is a myth that winning the vote was the end of women’s activism,” Fonow said. The proof is at the polls.

While critics were quick to pounce on reports of a low voter turnout for women in the first presidential election after the ratification of the 19th Amendment, subsequent history would begin to silence the naysayers. Just 36% of women cast a ballot in 1920 after a hard-fought battle that brought out 68% of men at the time. Almost a century later, the number of female voters has grown exponentially with a recent study showing voter turnouts for women had “equaled or exceeded” voter turnouts for men in recent elections.

Follow ASU Now on Twitter all year for more on the history of the 19th Amendment and the movement that made it happen. Top photo courtesy of the Library of Congress

More Law, journalism and politics

Can elections results be counted quickly yet reliably?

Election results that are released as quickly as the public demands but are reliable enough to earn wide acceptance may not always be possible.At least that's what a bipartisan panel of elections…

Spring break trip to Hawaiʻi provides insight into Indigenous law

A group of Arizona State University law students spent a week in Hawaiʻi for spring break. And while they did take in some of the sites, sounds and tastes of the tropical destination, the trip…

LA journalists and officials gather to connect and salute fire coverage

Recognition of Los Angeles-area media coverage of the region’s January wildfires was the primary message as hundreds gathered at ASU California Center Broadway for an annual convening of journalists…