With urban fishing, there’s a catch

Beth Polidoro is a marine biologist who leads ASU’s Salt Water Assessment Team lab and an associate professor of environmental chemistry and aquatic conservation in the New College of Interdisciplinary Arts and Sciences. Photo by Andy DeLisle

Anyone in the metro Phoenix area can fish in urban lakes and ponds and eat the fish they catch. The only thing required is a Class U (Urban) fishing license, which is $16 for the year. This makes fish an inexpensive source of protein available to residents of all income levels.

The Arizona Game and Fish Department prides itself on having the largest urban fishing program in the country, and they have plans to expand further. By 2025, they hope to be able to provide 200,000 urban fishermen the opportunity to fish within 5 miles of their homes.

But who is keeping track of any pollutants and chemicals in these waters and, by extension, the fish?

The answer is nobody. Beth Polidoro, an associate professor in Arizona State University’s School of Mathematical and Natural Sciences, thinks that’s a problem.

Since 1972, the Clean Water Act has provided security and peace of mind that the water we drink, bathe in and wash with every day is safe and monitored. The catch, according to Polidoro, is that if the waters are officially not designated for use, such as for recreational fishing under the Clean Water Act, they do not have to be monitored. Many of the urban lakes and ponds in metro Phoenix do not have a designated use.

Even if they were designated, Polidoro said, “Generally, some of the only things you're required to monitor for in waters designated for fishing is mercury, and maybe PCBs, depending on the state.”

In a 2019 pilot study, Polidoro and her team found phthalates (microplastics), PAHs (from combustion of organic materials like car emissions and forest fires), pesticides and metals in fish caught in several Phoenix lakes and ponds. This does not mean that the fish are toxic or dangerous, but it does suggest a need for increased monitoring across a more diverse suite of organic pollutants and heavy metals. The study was published in the journal Chemosphere.

“We’re finding a larger suite of contaminants in these fish that we would want to be included in a comprehensive monitoring program, not just mercury,” she said.

In a 2017 study published in the Journal of Environmental Quality, a graduate student working with Polidoro surveyed urban fishermen to gather their perceptions and uses of the fish being caught in Phoenix's urban lakes and ponds. The majority of those interviewed were eating the fish that they caught.

Polidoro notes that urban fishing is a great idea.

“If it’s done correctly and sustainably and with an outlook towards public health, it can be a really important source of protein for a lot of communities that enjoy fish, and where other protein sources might be really expensive,” she said.

However, a gap in regulation means that no one body or organization is responsible for keeping residents safe from contaminants in those fish.

The overall goal of Polidoro’s research is to assess risk. So instead of saying the pollutants found in the water and fish pose a risk for everyone, she looks at which chemicals are present in concentrations high enough to have potentially long-term adverse impacts on certain segments of the population. The fish being caught and eaten in the Phoenix area may be disproportionately affecting minority and lower-income populations. Pollutants in the fish could add up over time, posing health risks.

“There are chemicals everywhere in the world. It’s just a matter of trying to quantify the concentrations in the environment and then estimating different scenarios of adverse impacts based on which chemicals may be posing more of a risk to freshwater species and public health, if people are eating them,” she said.

Polidoro suggests a solution: “We need to get these lakes and ponds designated as waters of the U.S. by having a designated use, which is fishing. Then, we need to substantially expand the capacity and funding for the Arizona Department of Environmental Quality to regularly monitor these fish and waters for contaminants.”

The study also notes that we can help reduce contaminants in urban waterways by reducing pesticide use in urban parks, sports fields and golf courses, and by reducing single-use plastics and fossil fuel emissions.

Polidoro also believes we need to engage students, youth and community members in research. In fact, the lead author on the Chemosphere article was a high school student working in her lab.

Polidoro and her students developed an ASU STEM badge for Girl Scouts through this project. They trained more than 150 Girl Scouts, ages 5 to 15, to fish. The girls also learned about water quality, common sources of pollution and wildlife identification.

“We’ve really reached out and tried to engage community members so they can learn about STEM opportunities at ASU and also become more involved in the stewardship of their own environment in metro Phoenix,” Polidoro said.

This research was supported in part by funding from the USEPA Urban Waters Program (Grant #99T44001) and the National Fish and Wildlife Foundation Five-Star Urban Waters Program (Grant #1301.16.052536).

Written by Madison Arnold

More Science and technology

Podcast explores the future in a rapidly evolving world

What will it mean to be human in the future? Who owns data and who owns us? Can machines think?These are some of the questions…

New NIH-funded program will train ASU students for the future of AI-powered medicine

The medical sector is increasingly exploring the use of artificial intelligence, or AI, to make health care more affordable and…

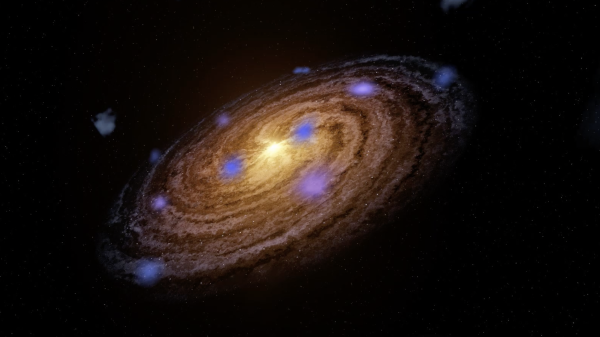

Cosmic clues: Metal-poor regions unveil potential method for galaxy growth

For decades, astronomers have analyzed data from space and ground telescopes to learn more about galaxies in the universe.…