ASU researchers use new tools of data science to capture single molecules in action

ASU professors Steve Presse and Marcia Levitus

In high school chemistry, we all learned about chemical reactions. But what brings two reacting molecules together? As explained to us by Albert Einstein, it is the random motion of inert molecules driven by the bombardment of solvent molecules. If brought close enough together, by random chance, these molecules may react.

Capturing the motion of single molecules is achieved by a method known as fluorescence correlation spectroscopy (FCS). The catch? It takes many detections of light particles – photons – emitted by single molecules to get a clear picture of molecular motion.

As an illustration, think of a political poll. At any given time in a campaign cycle, polls are used to predict the outcome of an upcoming election. But how many voters must we interrogate to get an accurate prediction and, given how time-sensitive polling information is, how quickly can we probe the nation’s political leanings? Asking every voter in every state would yield accurate results but be too costly in time and dollars. For practical reasons, we need to take a sample of voters and efficiently exploit all information contained in that sample. The voters in this illustration are our proverbial photons here.

“Single-molecule fluorescence techniques have revolutionized our understanding of the dynamics of many critical molecular processes, but signals are inherently noisy and experiments require long acquisition times,” explained Marcia Levitus, an associate professor in the School of Molecular Sciences and the Biodesign Institute at Arizona State University.

FCS takes too long, and the chemistry we care about learning might already be done by the time we try to observe it. Furthermore, exposing samples to the laser for long periods of time may result in the photochemical damage of molecules under study, preventing the widespread use of FCS in biological research.

A paper published in Nature Communications by ASU Associate Professor Steve Presse and collaborators now addresses these issues using tools from data science and, more specifically, Bayesian nonparametrics – a type of statistical modeling tool so far largely used outside the natural sciences.

This work leverages new tools from data science in order to make every photon detected count and refine our picture of molecular motion.

“New mathematical tools make it possible to think about old but powerful experiments in a new light,” said Presse, lead author on the study and joint professor in the Department of Physics and School of Molecular Sciences.

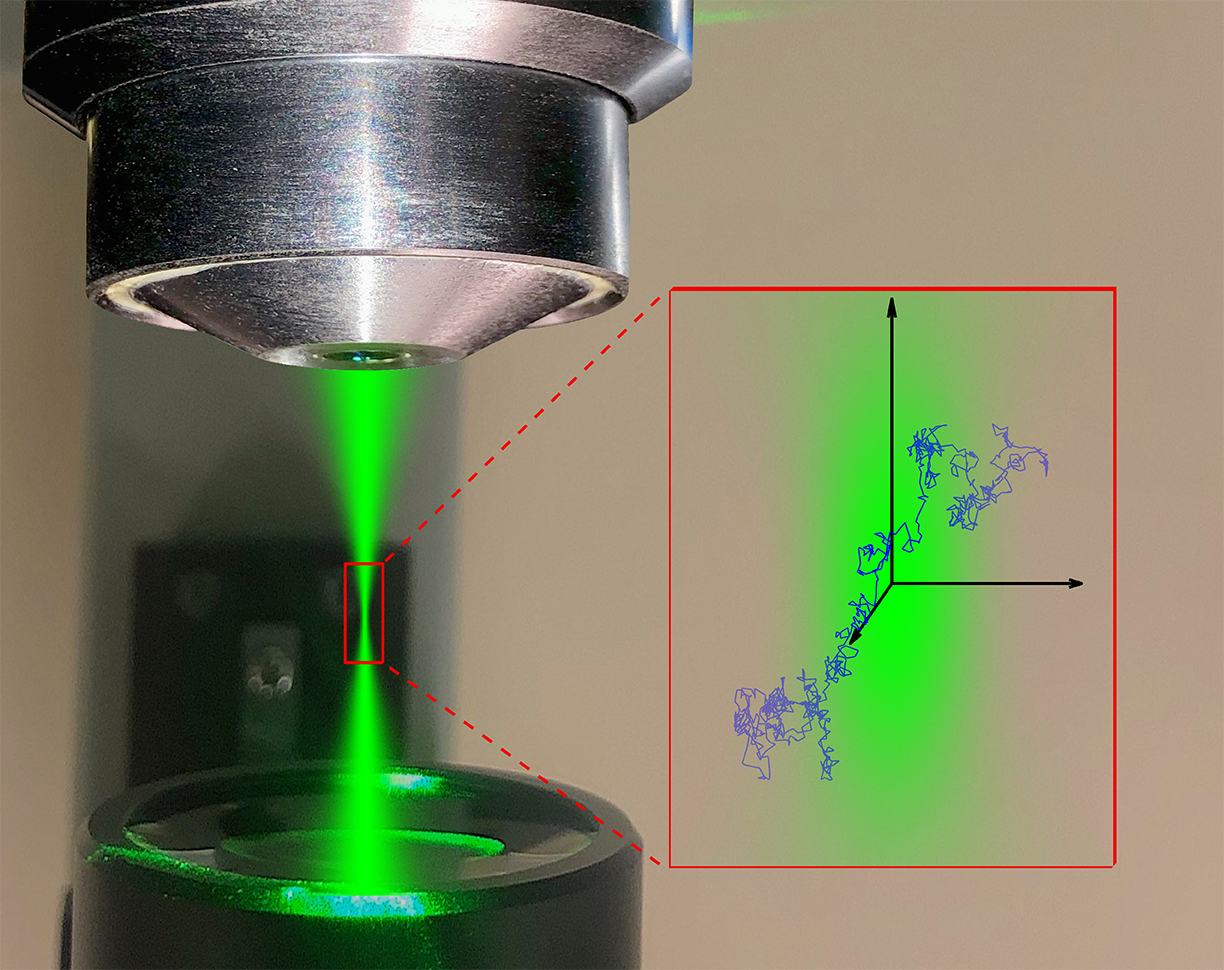

A molecule, whose path traced out in time is shown by the blue line, occasionally wanders into a brightly lit green region. Within this region, the molecule is excited and begins emitting light of a different wavelength that we can distinguish from the green light. This emitted-light reports back on the behavior of the molecule.

Levitus added, “Old strategies limited our ability to probe anything but slow processes, leaving a vast number of interesting biological questions involving faster chemical reactions out of reach. Now we can begin asking questions on processes resolved in short order.”

Presse’s team includes Sina Jazani, a graduate student, and Ioannis Sgouralis, a postdoctoral associate at the ASU Center for Biological Physics. The experimental collaborators and co-authors of the paper include Levitus, Sanjeevi Sivasankar, an associate professor at the University of California, Davis' Department of Biomedical Engineering and his graduate student Omer Shafraz.

More Science and technology

James Webb Space Telescope opens new window into hidden world of dark matter

NASA’s James Webb Space Telescope (JWST) has revealed unparalleled details about the early universe: observations of young…

US Department of Energy selects ASU and DCX to pioneer new ways to power data centers

The U.S. Department of Energy has selected Arizona State University and DCX USA, LLC, as key research partners for its…

From the lab to your headphones, new podcast brings ASU research to you

What do you get when an evolutionary biologist, an engineer and an anthropologist walk into a recording studio?At Arizona State…