With a literary oeuvre that includes 11 novels, several children’s books, plays, and even an opera, Toni Morrison long has been revered as one of the most accomplished and impactful writers in American literature. The Nobel and Pulitzer Prize-winning author died this week on Aug. 5, 2019, at the age of 88.

Over her six-decade career, Morrison cast light on the complexities of black American life through historical and contemporary contexts that chronicled the joys and anguishes of flawed narrators and characters in novels such as “Beloved,” “Song of Solomon,” “The Bluest Eye,” “Jazz,” “Love” and “Home.”

ASU Now asked several professors at Arizona State University to reflect on the authorship and scholarship of Morrison and weigh in on the impact of her popular, and controversial, body of work.

Neal Lester

Professor of English, Project Humanities founder

What I know about myself and the world has largely been the result of reading, teaching, studying and publishing on black women writers. Among the most influential in my personal and academic life was Toni Morrison. For over 30 years, I have taught and written about her novels, her single short story, her children's books, her interviews and her essays and speeches. A consummate storyteller, she took readers into worlds that were both comforting in their familiarities — black folks' cultural and linguistic rhythms and experiences — and challenging in their complex realities of our humanity and inhumanity. Whether writing about or discussing racism, colorism, sex and sexuality, incest, rape, trauma, women's friendships, American folklore, adultism, meanness or unconscious bias, Toni Morrison has gifted the world with an unparalleled body of work that humanizes even as it calls out injustice and inhumanity for what it really is — all in the spirit of making us better humans. To experience Morrison's work is to bask in the choreography of words that sing, soar and spiritually satisfy.

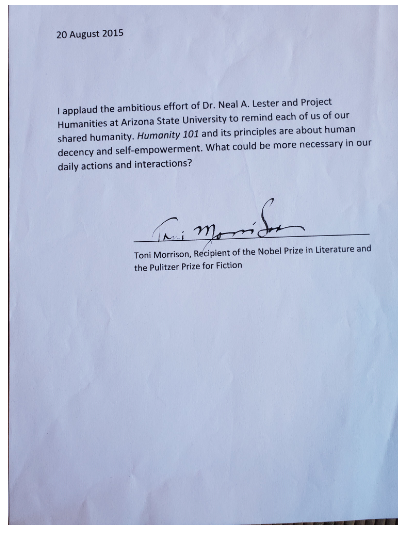

Toni Morrison's signed endorsement of Project Humanities' Humanity 101 at ASU

I had the chance to meet and dine with Toni Morrison several years ago at a special event held in her honor at Virginia Tech. I also took ASU students with me to meet her and all the literary greats who were there to celebrate Toni after her son died. Maya Angelou, Sonia Sanchez and Angela Davis were among the many who came out to celebrate her and give her flowers and appreciation. But we also had reason to celebrate by the end of the ceremony with the special gift Toni gave to us. At the invitation of poet and Project Humanities supporter Nikki Giovanni, who organized the event, Toni Morrison, Nobel laureate and Pulitzer Prize-winning author, enthusiastically endorsed our Project Humanities Humanity 101 efforts. It was her night to be honored and it was our honor as well.

Elizabeth Horan

Professor of English, comparative literature

One of America’s greatest novelists, Toni Morrison, born Chloe Anthony Wofford, was a divorced mother of two boys who published her first novel at the age of 39. She changed the way that we think about America and about fiction. Her novels put the complicated lives and rich culture of African American and other people of color front and center. For years now I’ve taught her novels, most often her classic “Beloved,” to ASU students in my “Nobel Prize in Literature” course, and we always talk about the authority and humanity of her characters, her wild sense of humor, her deft hand with history and the way that her language gives you goosebumps. In the course’s two main assignments — “Who will win the Nobel Prize for Literature this year” and “Who should win the Nobel for Literature in 20 years?” — the work of Toni Morrison is always the standard when student want to “nominate” a writer from the U.S. We mourn her death and cherish her words, her many fine novels and novellas, and her wise interviews that we will have with us always. She is my — our — hero.

Keith Miller

Professor of English, rhetoric

I argue that Toni Morrison is the greatest writer in American history. She learned from William Faulkner, who has often been called America’s greatest author, but far surpassed him, in my opinion. In his famous novel, “The Sound and the Fury” Faulkner writes from the perspectives of white characters but not from that of his major African American character — an implicit admission that he didn’t understand African American perspectives. Morrison, however, understood race. She brought to fruition the extremely far-sighted and now indispensable frameworks of intersectional analysis embodied in speeches by Sojourner Truth, Maria Stewart and Frances E.W. Harper before the Civil War. Better than anyone else, she brilliantly explains that, far from being separate from African Americans and Native Americans, white identity hinges on whites’ racial attitudes, which, to say the least, stigmatize nonwhites as inferior and as "other." In “Beloved,” which I often tell students is easily the best American novel, Morrison offers a trenchant critique of slave autobiographers such as Frederick Douglass and virtually every other American author, for ignoring the tortuous voyages of newly enslaved Africans across the Atlantic.

In Harlem this summer, I visited a friend who sells African American items, including a tote bag with a sketch of a slave ship and the caption, “Remember the Ride.” It reminds me of themes that run throughout Toni Morrison’s works. She says if Americans continue to ignore the slave voyages, followed by centuries of bondage and lynching, then the great experiment of America will never succeed.

Calvin Schermerhorn

Professor of history, African American studies

I was introduced to Toni Morrison 25 years ago this fall. My lit professor skipped the small stuff in assigning Toni Morrison’s “The Bluest Eye” and correctly deciding that a group of students from the Maryland suburbs needed such perspective on the intricate interplay of race, gender and poverty constructed in direct, elegant, searching language. I couldn't put it down, taking Pecola Breedlove — the pivotal character — on a walk down to where my college was about to move one of the last standing slave cabins in the state so archaeologists could see what was buried under it.

Toni Morrison's excavation of race was much more illuminating to a white boy whose previous exposure to novels of social conflict had been “Johnny Tremain,” “The Outsiders” and “A Separate Peace.” These now all seemed to be puddle water compared to the clear-eyed, yet impossibly complex ugliness of American racism beautifully and seductively rendered by a writer whose influence shaped my career as a historian of slavery and racial inequality.

Melissa Pritchard

Professor emeritus, English, women’s studies and fiction writer

There are two ways Toni Morrison affected me personally. First, while I was a divorced, single mother of two girls, trying to keep food on the table, write and publish, hold onto my dreams, I was lonely a lot of the time — I had no social life at all. Then I read an interview with Toni Morrison, where someone asked her how she managed to be an editor in New York City, plus raise two boys alone. "I have no social life," was her plain answer. It was an answer that saved me, let me know I was OK, maybe even on the right path — that a sacrifice needed to be made and, in my case, it was not writing or the well-being of my daughters but the relatively easy giving up of parties, dinners, companionship. Those things came, eventually, but Toni Morrison's honest, five-word answer to her interviewer's question was a lifeline I will always be thankful for.

Secondly, when everyone was talking about Toni Morrison, whatever her newest book was, I resisted — an arguably self-sabotaging habit I've had since high school — to avoid what is popular. Then I sat down one day and read “Beloved.” As I read, I could not breathe, I was in shock at the breadth, beauty and brutality of this novel, a way of writing, of speaking to the world through fiction, that I hadn't experienced since reading Gabriel Marquez's “One Hundred Years of Solitude.” But what Morrison was writing about hit closer to home. Was home. I could not begin to compare my writing to hers — that felt almost profane, dangerous, too, as I would be tempted to give up writing altogether. Instead, I gave myself over to her power, to the power of “Beloved” and experienced that tearful welling up of gratitude one feels so rarely in life, in the presence of titanic genius.

James Blasingame

Professor of English, young adult literature

“As you enter positions of trust and power, dream a little before you think.” Toni Morrison provoked us to think — and to think critically through her work. It is what we are tasked to teach our students as educators and it why when a local school district tried to ban Morrison’s novel “Beloved” from its curriculum several years ago, fellow Professor of English Sybil Durand and I stepped up the efforts to keep this important work in schools.

School board members asked for our help as experts on high school curriculum to provide useful information for when the challenge came to a vote, including legal and literary considerations. In addition to legal precedents that have determined a school cannot remove a book because objectors do not share its political or societal ideas, we argued that the study of literature is an important component of learning how to think through dilemmas and can help shape character — on and off the page. Morrison’s work was purposefully complex — just like life itself — and stories like “Beloved” can help people form ethical and moral decisions in their own lives. In the end, the school board agreed — “Beloved” would remain in the school’s curriculum.

Toni Morrison touched millions of hearts and minds and helped society to find the best in itself. As many people have said (this week), although Ms. Morrison is gone, her writing will live on.

Top photo: Toni Morrison, Flickr/Christopher Drexel

More Arts, humanities and education

AI literacy course prepares ASU students to set cultural norms for new technology

As the use of artificial intelligence spreads rapidly to every discipline at Arizona State University, it’s essential for students to understand how to ethically wield this powerful technology.Lance…

Grand Canyon National Park superintendent visits ASU, shares about efforts to welcome Indigenous voices back into the park

There are 11 tribes who have historic connections to the land and resources in the Grand Canyon National Park. Sadly, when the park was created, many were forced from those lands, sometimes at…

ASU film professor part of 'Cyberpunk' exhibit at Academy Museum in LA

Arizona State University filmmaker Alex Rivera sees cyberpunk as a perfect vehicle to represent the Latino experience.Cyberpunk is a subgenre of science fiction that explores the intersection of…