Phoenix lawyer expands human rights work legacy at ASU and abroad

Patience Huntwork is a staff attorney at the Arizona Supreme Court and a board member at The College's Melikian Center.

In 1985, Patience Huntwork was freshly graduated from Yale Law School and working in Phoenix when an article about the American Bar Association and the Soviet Lawyers Association caught her eye.

The Phoenix Gazette article referenced an opinion piece penned by lawyer Alan Dershowitz alleging the Soviet Lawyers Association had close ties to USSR leadership and encouraged the American Bar Association to sever ties.

She gathered fellow attorneys and activists from the Phoenix area for a campaign that aimed to convince the U.S. legal body to stop cooperating with its Soviet counterpart for good. For 16 months, they picketed American Bar Association meetings, waving the national flags of the 15 states under Soviet rule at the time.

The campaign succeeded. By 1987, just before the fall of the Soviet Union in 1991, the relationship between the two legal bodies ended.

It’s been almost three decades since then, and Huntwork, now a staff attorney at the Arizona Supreme Court, has continued to advocate for legal reform and empowerment in former Soviet countries.

That was the impetus behind her involvement in the Critical Language Institute at Arizona State University. Part of The College of Liberal Arts and Sciences’ Melikian Center for Russian, Eurasian and East European Studies, the institute focuses on less commonly taught languages deemed important to national security and international affairs.

With seed funding from Huntwork and her husband, James, the institute introduced Ukrainian as its 12th language in 2017.

“As a board member of the Melikian Center and longtime friend of the Melikians, I keep hearing about what a critical language Russian is,” she said. “But at the same time, Ukraine was becoming increasingly important in the eyes of the world.”

Huntwork has also put that idea to work in her own efforts. She served in the Ukrainian presidential election as an official observer at the polls this March, the latest in a series of trips she and her husband have taken to Ukraine since 2014.

She answered a few questions about her time abroad, the courses she heralded at the Melikian Center and the role of language as a tool for the future.

Question: What is your history with the Melikian family and the center?

Answer: I met Emma and Gregory Melikian during that first campaign in 1985. They were part of a group of people my husband and I worked with, including several dissidents from the Soviet Union. We have kept in touch over the years, which is why they asked me to be on the board of the Melikian Center a few years ago. That’s how I ended up working to bring Ukrainian courses to the center. The language is becoming increasingly important, and it shows.

Q: How so?

A: Today, the people you see taking Ukrainian at the Melikian Center are very diverse. One young man took classes at the center because he is going to Ukraine with the Peace Corps.

Another is graduating with a degree in international business development and simply wants Ukrainian skills in his portfolio. Another wrote a novel based in Ukraine and another is training to be a medic in response to the country’s war. I think the importance of this language is proved by the fact that students from so many different backgrounds are taking part, and I hope to see that grow even more.

Q: That interdisciplinarity is also a core principle at The College. How do you think language skills can assist students entering the workforce in a number of different fields today?

A: Whatever field you end up in, being able to speak another language is a tool. The Ukrainian language is something so attuned to national identity, for example, so we send a powerful message by embracing it. That is also the case for all the other languages at the Melikian Center and the Critical Language Institute. I also think that ASU prides itself on being able to positively impact the world — speaking a language gives you the power to do that.

Q: What did your work as an electoral overseer entail?

A: My husband and I observed two elections in 2014 — the presidential election and the parliamentary election. We did the same thing earlier this year, during the presidential elections in March.

We went as observers with the Ukrainian Congress Committee of America, which has the second-largest delegation of observers. To do it, we applied and were accepted through the committee’s website, which then forwarded the applications to the Ukraine Central Election Commission for approval.

On election day, you fill out an assessment form describing what’s going on at your assigned precinct. National organizers collect these assessments from all over the country to get a clear idea of what’s going on.

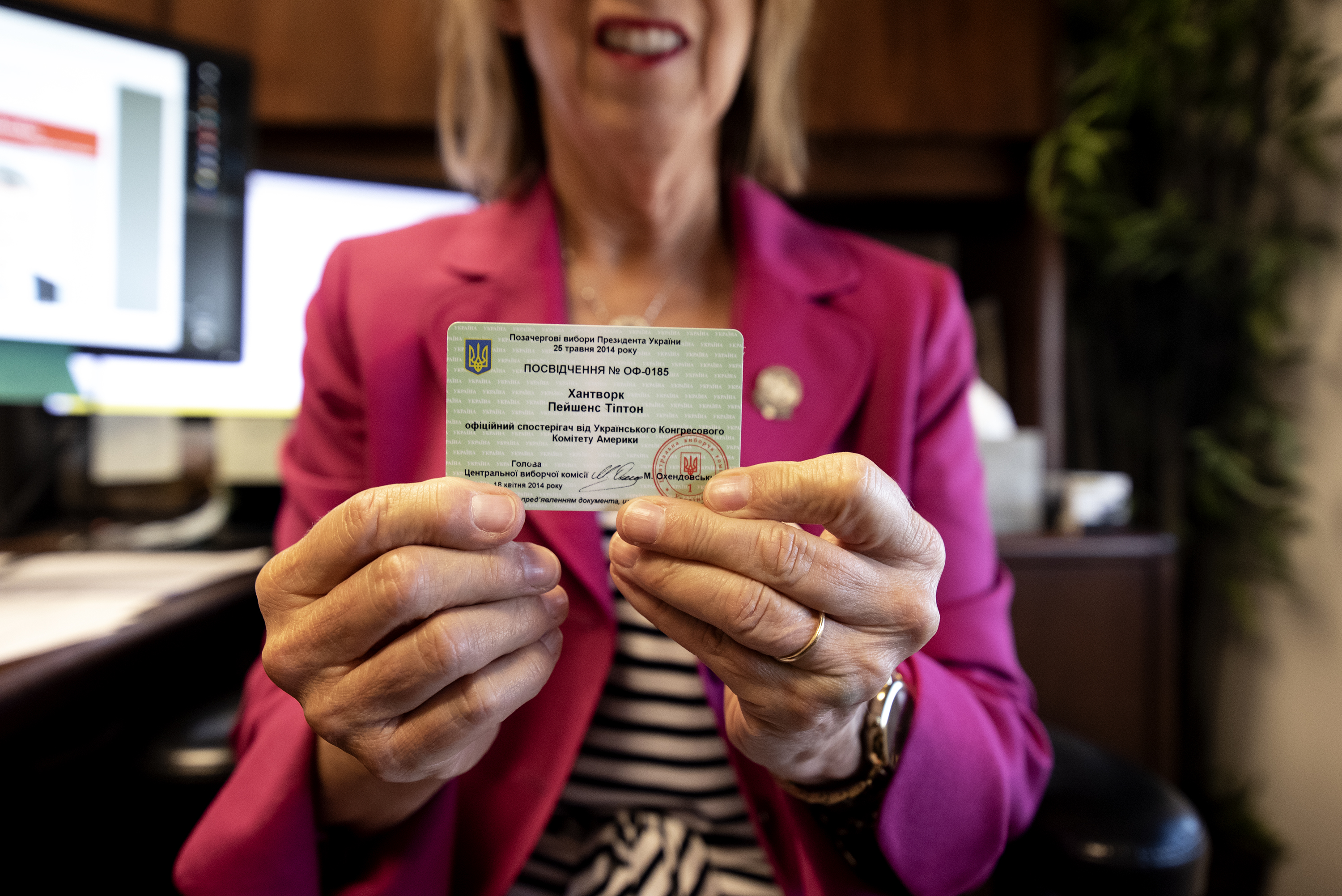

Huntwork shows her overseer ID card issued during this year's Ukrainian presidential election.

Q: What is something you learned in the process or would like others to know?

A: I was impressed by how expertly organized the elections themselves were. Ukraine is one of the most literate countries in the world, so the people that carry out the election are incredibly well informed and educated about the process. In many ways, some of our own elections here in Arizona could benefit from some of that organization and access to the polls.

Q: What did you take away from the experience and what do you think young people can take away from your activism?

A: All the crazy, supposedly hopeless efforts, from picketing in 1987 to speaking about it later, actually turned out to be successful. I have been involved in a lot of other activism here locally since then, including for homeless populations in Phoenix and other legal issues. But the campaign in 1985 has really been one of those threads that’s carried through my whole career and informed my work at the Melikian Center as well as in the Ukrainian elections. I think this is all to say that hearing you can’t do something shouldn’t stop you from trying, because sometimes you actually succeed.

More Arts, humanities and education

ASU professor's project helps students learn complex topics

One of Arizona State University’s top professors is using her signature research project to improve how college students learn…

Award-winning playwright shares her scriptwriting process with ASU students

Actions speak louder than words. That’s why award-winning playwright Y York is workshopping her latest play, "Becoming…

Exceeding great expectations in downtown Mesa

Anyone visiting downtown Mesa over the past couple of years has a lot to rave about: The bevy of restaurants, unique local shops…