ASU researcher finds first fossilized evidence of collective behavior

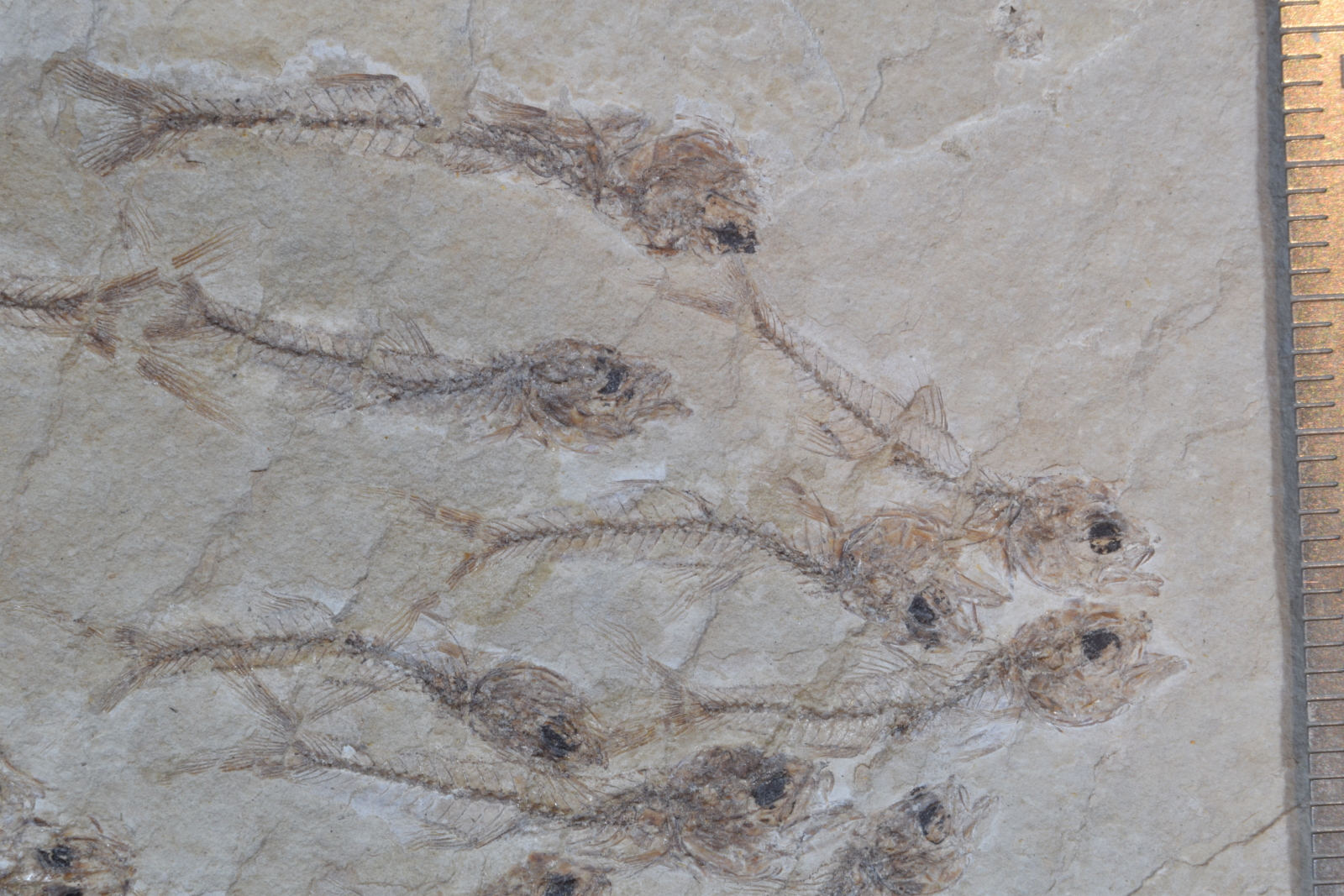

In this 50 million-year-old slab of limestone shale, 259 fish from the extinct species Erismatopterus levatus show social behavior similar to behavior performed in many live fish species. Photo by Nobuaki Mizumoto/ASU

Wherever animals live together as groups, behavior patterns emerge.

In a flight across the world, this is apparent in the square patches of land that mark property boundaries. Flights across all countries — from America to Japan — reveal similar land use patterns.

Nobuaki Mizumoto has always been fascinated by the evolution of these patterns. However, studying behavior requires live specimens.

Or so he thought until he discovered an interesting photo of a fossil in a small museum in his Japanese hometown, the Fukui Prefectural Dinosaur Museum, in Katsuyama, Japan.

Mizumoto, a postdoctoral researcher with Arizona State University’s School of Life Sciences, recently analyzed that photo to discover the first fossilized evidence of collective behavior, which was published this week in the scientific journal “Proceedings of the Royal Society B.”

By analyzing the photo of an extinct fish species (Erismatopterus levatus) in slab of limestone shale, Mizumoto and co-author Stephen Pratt, an associate professor in the school, discovered social behavior similar to that seen in live fish species. The fish are preserved in a stone, originally from an area near Wyoming, thought to be at least 50 million years old.

The 259 fish were grouped in a circle similar to what is seen in fish that travel in groups, and they seemed to adhere to two general rules seen in many fish species: attraction and repulsion. When traveling in groups, individuals don’t want to be isolated from the group but they also want to avoid collisions with one another.

Therefore, individuals who are very close to others should want to move slightly away from the group while individuals who are farther away should want to move toward it.

But how can Mizumoto tell from a photo if the fish were actually doing this? He has never studied fish. His expertise is live termites. And because he was attempting to do something that had never been done before, he had to develop his own methodology.

“This has never been done in a fossil. First of all, behavior is rarely preserved in fossils,” Mizumoto said. “In behavior studies, we use videos. I watch hours of videos, but this is only one snapshot, which is very difficult. I looked at where the fish were in relation to one another. It looked like these individuals that were farther away were pointing toward the group while those that were closer were pointing away to make distance. I had to figure out how to describe this, and finally, I thought ‘I can move them’ and see where they would end up if they kept moving.”

Mizumoto created a computer simulation where he moved each fish slightly in the direction it was pointed to see where it would go if it continued moving. He found that these fish did seem to be following both the rules of attraction and repulsion based on their proximity to the other fish.

Based on Mizumoto's simulation, fossilized fish appear to be following two key rules of social behavior: repulsion to avoid collison to nearby individuals and attraction to those farther away to avoid isolation. Photo by Nobuaki Mizumoto/ASU

However, the complication with this study is that this fish species and all related species are extinct, so the results cannot be compared to live fish. In addition, since these fossils have been preserved for 50 million years, Mizumoto and his colleagues have no idea how they died and could not be certain they were performing this behavior in death.

To account for this, Mizumoto included wind and water currents into his analysis to see whether this could explain the results. Neither could explain the connection between direction pointed and proximity to neighbors, which opens the door for using fossils to study the evolution of behavior.

“There is very little precedent for this, and of course there are many caveats, having to do with our uncertainty about how a given fossil was preserved and whether we can distinguish the signs of behavior from processes external to the animals,” Pratt said. “A paleontological perspective has been largely absent from the study of collective behavior. I hope that this study inspires other people to seek fossil evidence whose value may not have been appreciated before.”

Initially, Mizumoto started this project because it combined his hobby of visiting fossil museums with his research interests in social behavior. However, he hopes that by sharing this picture, he will learn of other photos of fossilized behavior that can be analyzed for more information.

“I think it is a very good fossil, but it is in a corner of a very small museum in Japan, and I thought, 'I want to share this photo all over the world,'” Mizumoto said. “I don’t know if these photos are rare or not, but if there are other photos like this out there, I might get the chance to analyze more. If we can find other examples and some of them are similar, that will give us more information.”

More Science and technology

ASU student researchers get early, hands-on experience in engineering research

Using computer science to aid endangered species reintroduction, enhance software engineering education and improve semiconductor…

ASU professor honored with prestigious award for being a cybersecurity trailblazer

At first, he thought it was a drill.On Sept. 11, 2001, Gail-Joon Ahn sat in a conference room in Fort Meade, Maryland.…

Training stellar students to secure semiconductors

In the wetlands of King’s Bay, Georgia, the sail of a nuclear-powered Trident II Submarine laden with sophisticated computer…